As divisive reactions to 28 Years Later continue to take shape, the movie has inspired some side chat about how, exactly, we’re expected to think about 28 Weeks Later, the other 28 Days Later sequel.

Now that Boyle and Garland have made their own sequel, it feels like 28 Weeks Later has been squeezed out – especially because Boyle, Garland, 28 Days Later star Cillian Murphy, and 28 Weeks Later star Rose Byrne had another genre thriller that was released almost simultaneously with that 2007 film: Sunshine, a visionary sci-fi flop that nonetheless feels of a piece with Boyle’s two horror movies.

28 Weeks Later came out at a more typical follow-up speed in 2007 and in the last 18 years has not maintained its predecessor’s staying power. In fact, 28 Years Later starts with a title card that explains that, while the rage virus spread into the rest of Europe, seen in a memorably bleak final shot of the 2007 film’s finale, it was ultimately beaten back to England, undoing but not erasing the movie’s ending. As Years opens, the rest of the world has remained safe for many years, while the United Kingdom is under strict quarantine.

But beyond questions of here-and-now continuity, 28 Weeks Later remains an odd fit with its siblings. The 28 Years Later walk-back of its ending comes after 28 Weeks Later itself appends a clear resolution to the original movie after the fact (showing that in those 28 weeks, the rage virus has mostly been wiped out and England is supposedly ready to be re-inhabited) before then undoing that with its own story (which shows how the virus reemerges). So when part of that story is then walked back by the newest installment, 28 Weeks Later looks even more like a false start. It doesn’t help that the movie, well-made as it is by director Juan Carlos Fresnadillo, wasn’t written by Garland or shepherded by Boyle, who hired Fresnadillo and executive-produced the film but by all accounts let the new filmmaker do his own thing. Which, on its own, is great! More sequels should be given that level of autonomy, and 28 Weeks Later is certainly worth a watch.

But when it comes to thematic cohesion, Sunshine is a much snugger fit between Boyle’s two 28 movies.

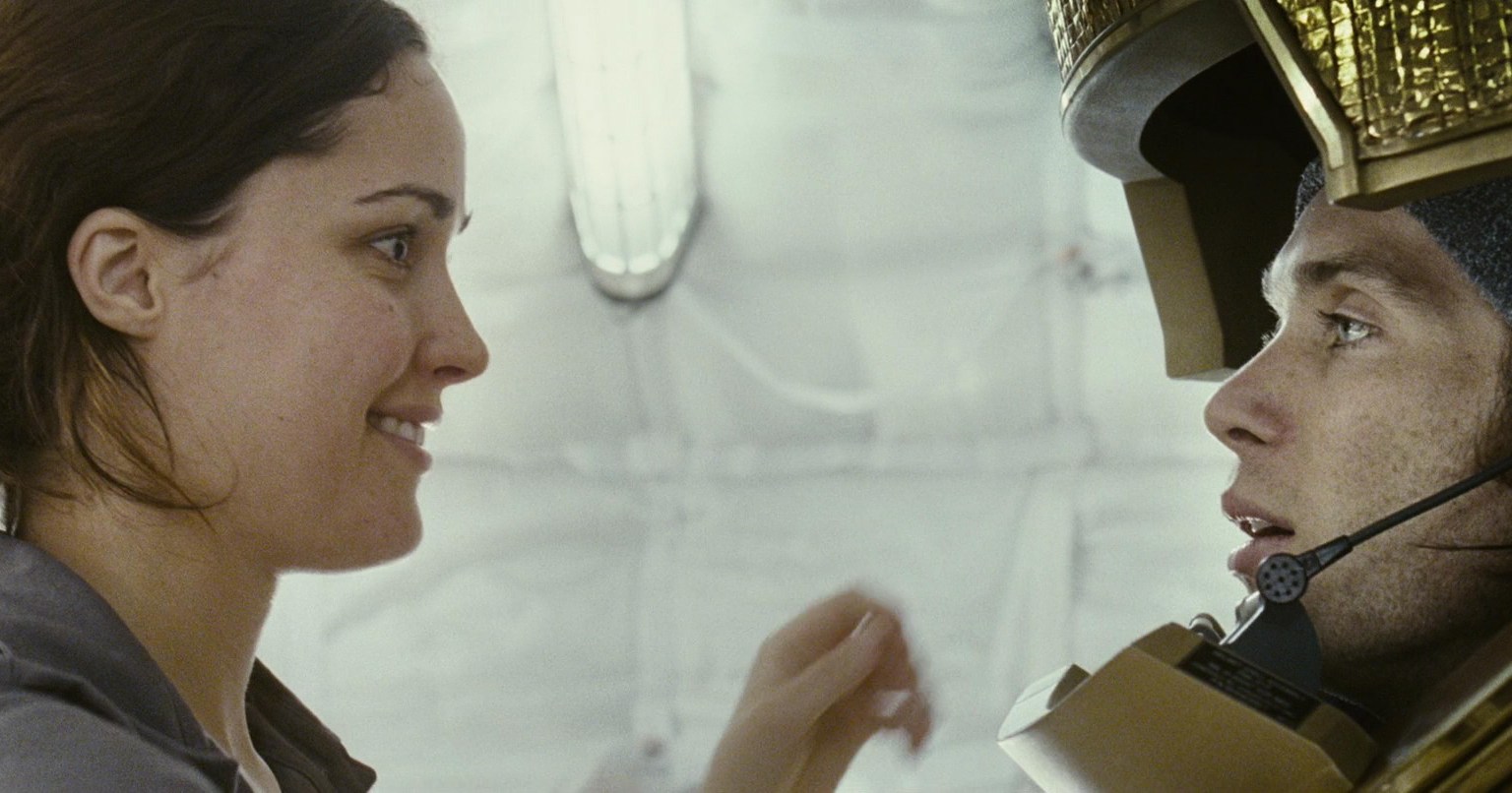

Just as 28 Days Later takes a familiar genre idea – the zombie apocalypse – and approaches it from an unusual angle, Sunshine essentially runs back the asteroid-mission disaster-movie double feature of 1998. While Deep Impact and Armageddon had drastically different styles, both of them were stories about Earth facing a cosmic yet naturally occurring threat, and a long-odds shuttle mission designed to save humanity. In Sunshine, Earth isn’t threatened by an asteroid but the sun itself, which is dying. A team of astronauts and scientists including physicist Robert Capa (Cillian Murphy, remaining Boyle’s experiential face of existential threats) has been tasked with bringing an enormous nuclear payload to the dying star and, essentially, jump-starting it back to life, not unlike the mission to blow up this or that threatening asteroid.

In terms of mood, Sunshine picks up more or less from where 28 Days Later leaves off, rather than the this-no-wait-that contradictions of its actual sequel. 28 Days Later ends with Britain still quarantined, with the emotional respite of Jim (Murphy) still alive after another long episode of unconsciousness. He and his small group of allies face both a bleak situation and more than a glimmer of hope, as the movie ends with a plane overhead looking as if it might bring aid to the stranded survivors, though help is far from assured. Similarly, the mood on the spaceship Icarus II isn’t exactly cheery. (I mean, the ship’s designation, from its name to its number, is not encouraging) A previous mission has already failed. (Seriously, Icarus?) Still, the job is undertaken with the hope that Earth can be saved, and that the crew might not even die trying.

Boyle and Garland depict their mission without ever cutting back to any form of mission control. (The movie doesn’t show any action on Earth until its final scene.) This creates a form of quarantine, with the eight-person crew creating a makeshift community somewhere between the skeleton crew of survivors in 28 Days Later and the more robust island community in 28 Years Later. While traditionally post-zombie groups have functioned as microcosms of society, Sunshine has the crew represent humanity in a different way. They do express some differences in problem-solving and some interpersonal animosity, but as a collective, the crew is singularly concerned with the survival of their species, possibly at the expense of themselves. This is inverse concern of the 28 Years Later community that seeks to quarantine from the outside world, using it only as a means of conducting its own coming-of-age rituals and presumably some supply-mining.

Moving from seeking basic survival (in Days) to humanity’s survival (in Sunshine) to the protection of a single community above all else (in Years) is, granted, not a natural, linear progression. But at times, the three movies feel like photographs taken of the same subject from vastly different vantage points – something further reflected in their respective visual styles. All three movies have drastically different looks: Days was shot on early digital video, giving it a blotchy, pixelated look of consumer-grade immediacy; Sunshine used a variety of techniques, including 65mm celluloid, to capture deep blacks and the unsettling glow of a too-close sun; and Years returns to digital but using customized iPhone rigs for imagery of greater clarity chased with otherworldly qualities. Yet all three movies, even the largely film-shot Sunshine, are using their individual visual styles for similar aims.

28 Days Later filters “reality” through miniDV pixels in a way that first makes an abandoned London look more real and later, more intense actions look increasingly abstract and nightmarish. Sunshine does something similar as it gets closer to the sun; a late-movie sequence set within the massive nuclear payload shifts the environment from the intricacy of a spaceship to the more abstract space of what looks like a gigantic cube of glowing lights. Once the movie crosses this threshold, it uses stuttering freeze frames as means of inserting disorienting micro-pauses into the most frenzied points of action, a technique further adopted by 28 Years Later.

Across the movies, Boyle uses his camera to capture “reality” in ways that are so vivid that they threaten to bend and break their own visual formats, a kind of hyperreality in disguise. (This is something that 28 Weeks Later, for all the sturdiness of its craft, doesn’t really do.) Before things in Sunshine go truly haywire, Boyle often frames characters through various filters – screens, reflections, read-outs – that put some digital distance between the people and their environment, which is eventually stripped away when they encounter the terrifying raw power of the sun, depicted in overexposed blasts that distort the image.

That mind-and-body-altering sun power also leads to the consensus least-liked element of Sunshine: the fact that it turns into something of a slasher movie in its final stretch. As the crew weathers a number of disasters involving their effort to collect a second payload from the distress-signaling original Icarus, they eventually encounter Icarus captain Pinbacker (Mark Strong), whose exposure to the sun’s power has convinced him that God has told him to sabotage the missions, allowing the whole of humanity to reach heaven. This inspires him to systematically attempt to murder any and all remaining crew members. These slashery overtones aren’t a cheapening of the previous hour-plus, however; they’re perfectly in keeping with the buggy, frayed-nerve finales of other Boyle movies. The visual effects employed to portray Pinbacker are astonishingly effective, blurring and distorting the image of his sunburned body so that the movie can’t ever face him head-on.

various VOD platforms.

various VOD platforms.

The post The real bridge between 28 Days and 28 Years Later isn’t a zombie movie appeared first on Polygon.