For more than 40 years, the United States—a nation that putatively cherishes freedom—has had one of the largest prison systems in the world. Mass incarceration has been so persistent and pervasive that reform groups dedicated to reducing the prison population by half have often been derided as made up of fantasists. But the next decade could see this goal met and exceeded: After peaking at just more than 1.6 million Americans in 2009, the prison population was just more than 1.2 million at the end of 2023 (the most recent year for which data are available), and is on track to fall to about 600,000—a decline of roughly 60 percent.

Discerning the coming prison-population cliff requires understanding the relationship between crime and incarceration over generations. A city jail presents a snapshot of what happened last night (for example, the crowd’s football-victory celebration turned ugly). But a prison is a portrait of what happened five, 10, and 20 years ago. Middle-aged people who have been law-abiding their whole life until “something snapped” and they committed a terrible crime are a staple of crime novels and movies, but in real life, virtually everyone who ends up in prison starts their criminal career in their teens or young adulthood. As of 2016—the most recent year for which data are available—the average man in state prison had been arrested nine times, was currently incarcerated for his sixth time, and was serving a 16-year sentence.

Because of that fundamental dynamic, the explanation for why roughly 1.6 million people—more than 500 for every 100,000 Americans—were in a state or federal prison in 2009 has very little to do with what was happening on the streets or with law-enforcement policies that year. Rather, the causes lay in the final decades of the 20th century.

From the end of World War II until the mid-1970s, the proportion of Americans in prison each year never exceeded 120 per 100,000. But starting in the late 1960s, a multidecade crime wave swelled in America, and an unprecedented number of adolescents and young adults were criminally active. In response, the anti-crime policies of most local, state, and federal governments became more and more draconian. The combined result was that the prison population exploded. By 1985, the imprisonment rate had doubled from its historical norm, such that more than 200 in 100,000 Americans were in a state or federal prison. The number of people in prison increased an average of 8 percent a year for the next decade, breaching the 1 million mark in 1994 and continuing to grow until 2009. This had ramifications that were felt for years: Because most people who are released from prison return, the system has been stocked and restocked with the legacy of that American crime-and-punishment wave for a quarter century. That’s why the 2009 peak of U.S. imprisonment came 18 years after the 1991 peak in the violent-crime rate. The prison system is like a badly overloaded tractor trailer—it takes a long time to stop even after the brakes are hit.

That tractor trailer is finally slowing down, decades after the “great crime decline” began in the 1990s. Until 2009, the lengthier sentences handed down during the preceding crime wave and the tendency of released prisoners to be re-incarcerated kept imprisonment rising even as crime declined. But the falling crime that the U.S. experienced in the 1990s and 2000s is now finally translating into a shrinking prison population.

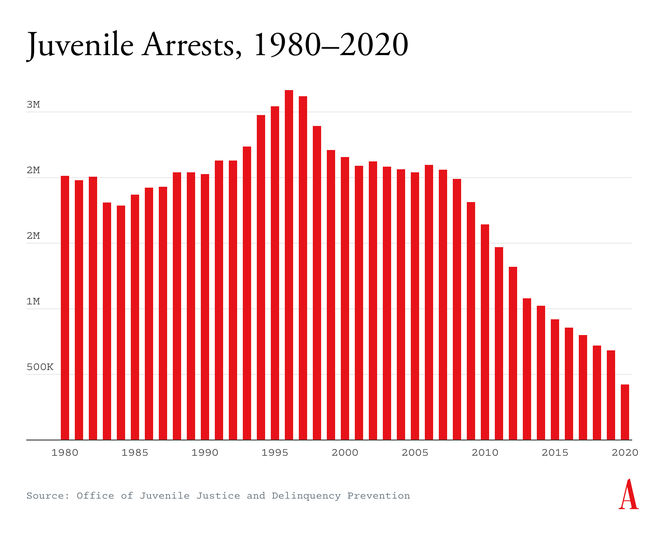

This chart, using data from the U.S. Department of Justice, shows the collapse of criminal arrests of minors in the 21st century. Rapidly declining numbers of youth are committing crimes, getting arrested, and being incarcerated. This matters because young offenders are the raw material that feeds the prison system: As one generation ages out, another takes its place on the same horrid journey. The U.S. had an extremely high-crime generation followed by a lower-crime generation, meaning that the older population is not being replaced at an equal rate. The impact of this shift on the prison population began more than a decade ago but has been little noticed because it takes so long for the huge prison population of longer provenance to clear.

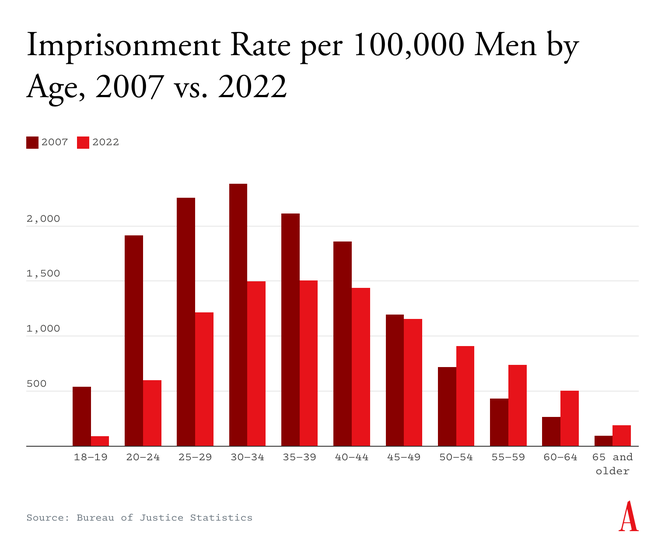

But such a transformation is now well under way. One statistic vividly illustrates the change: In 2007, the imprisonment rate for 18- and 19-year-old men was more than five times that of men over the age of 64. But today, men in those normally crime-prone late-adolescent years are imprisoned at half the rate that senior citizens are today.

As the snake digests the pig year after year, the American prison system is simply not going to have enough inmates to justify its continued size or staggering costs. Some states that are contemplating expanding their prison capacity will be wasting their money—their facilities will be overbuilt and underused. By 2035, the overall imprisonment rate could be as low as 200 per 100,000 people. States should instead be tearing down their most deteriorated and inhumane correctional facilities, confident that they will not need the space.

This optimistic analysis could have been written in 2019, when the imprisonment rate had been falling for more than a decade and hit a level not seen since 1995. I thought about writing this article then, but a world turned upside down shook my confidence.

COVID initially looked like a boon for decarceration because states reduced prison admissions and accelerated releases in 2020 to reduce transmission, cutting the prison population by 16 percent. But whether it was due to this mass release, COVID, de-policing, other factors, or some combination thereof, crime exploded in 2020 after a long quiescent period, most shockingly with an unprecedented 30 percent increase in homicides. Crime spikes increase incarceration directly because more people are committing crimes and also because they lead the public to demand more aggressive policies, which often translate into longer and more frequent prison sentences. If the turmoil of the early 2020s had led to an extended period of high crime and high punishment similar to what the U.S. experienced in the late 20th century, the COVID-era contraction of the prison population could have been immediately nullified and then some when, in the ensuing years, the prison pipeline was eventually replenished.

But thankfully, the spike was just a spike, not a new equilibrium. Crime stopped rising sometime in 2022, and fell in 2023 and 2024. The prison population inched up 2 percent in 2022 and again in 2023, and it is possible that a similar rise took place in 2024, but even collectively, this is a fraction of the sudden population decline during the early pandemic. The COVID era ended with prison populations lower rather than higher: A recent Vera Institute report found that, on balance, from 2019 to the spring of 2024, the number of federal prisoners declined by 11 percent, and the number of state prisoners declined by 13 percent.

Accelerating the de-prisoning of America is worthwhile and possible. The benefits of a smaller prison population are not limited to those who would otherwise be locked up and the people who love them. Prisons crowd out other policy priorities that many voters would like the government to spend more money on. In all 50 states, the cost to imprison someone for a year significantly exceeds the cost of a year of K–12 education. But even greater than the financial savings would be the prosperity in human terms: Less crime and less incarceration are profound blessings for a society.

The simplest available policy to accelerate the decarceration trend is to stop building prisons except in cases where a smaller, modern facility is replacing a larger, decaying institution. Though it will be nonintuitive to many reformers, particularly on the left, opposition to any such new facilities being private should be dropped. The principal political barrier to closing half-full prisons is the power of public-sector unions. In contrast, a private prison can be sent to its reward if its contract is canceled. Individual communities in areas of low employment will also fight to keep their prisons. Prison-closing commissions, analogous to military-base-closing commissions, may be necessary and should coordinate with legislators to provide worker retraining and financial assistance to compensate for the loss of high-wage jobs in communities whose economy revolves around corrections.

Finally, America should not let its prison system become the most expensive and inhumane of nursing homes. The rate of recidivism among senior citizens is near zero, and compassionate release of sick and aging inmates should be the default rather than the exception, a reversal of current practice.

In any given future year, small rises in imprisonment are possible, but the macro trend is ineluctable: Society is going to experience the benefits of past decades of lower crime throughout its prison system. The imprisonment rate will be lower in five years and lower still in 10. Prisons will still exist then and still be needed, but the rate at which Americans are confined in them could be lower than anything in the preceding half century. This is the fruit of a lower-crime society—good in and of itself, surely, particularly for the low-income and majority-minority communities where most crime occurs. It will also, of course, be a blessing for those who avoid prison, and for the taxpayers who no longer have to pay for it. The decline in the prison population will be something everyone in our polarized society will have reason to celebrate.

The post America’s Prison Population Is Finally in Serious Decline appeared first on The Atlantic.