I.

A Parliament of Billionaires

Donald Trump is America’s first billionaire president. He entered the White House in 2017 with a net worth of $3.7 billion, according to Forbes, and in 2025 with a net worth of $5.2 billion. Trump’s habitat, unlike yours or mine, is crowded with billionaires. His primary residence outside the White House is in Palm Beach, home to 68 billionaires, including the financiers Stephen Schwarzman and Ken Griffin, who—just those two—spent a combined $144.2 million to elect Trump and other Republicans in 2024.

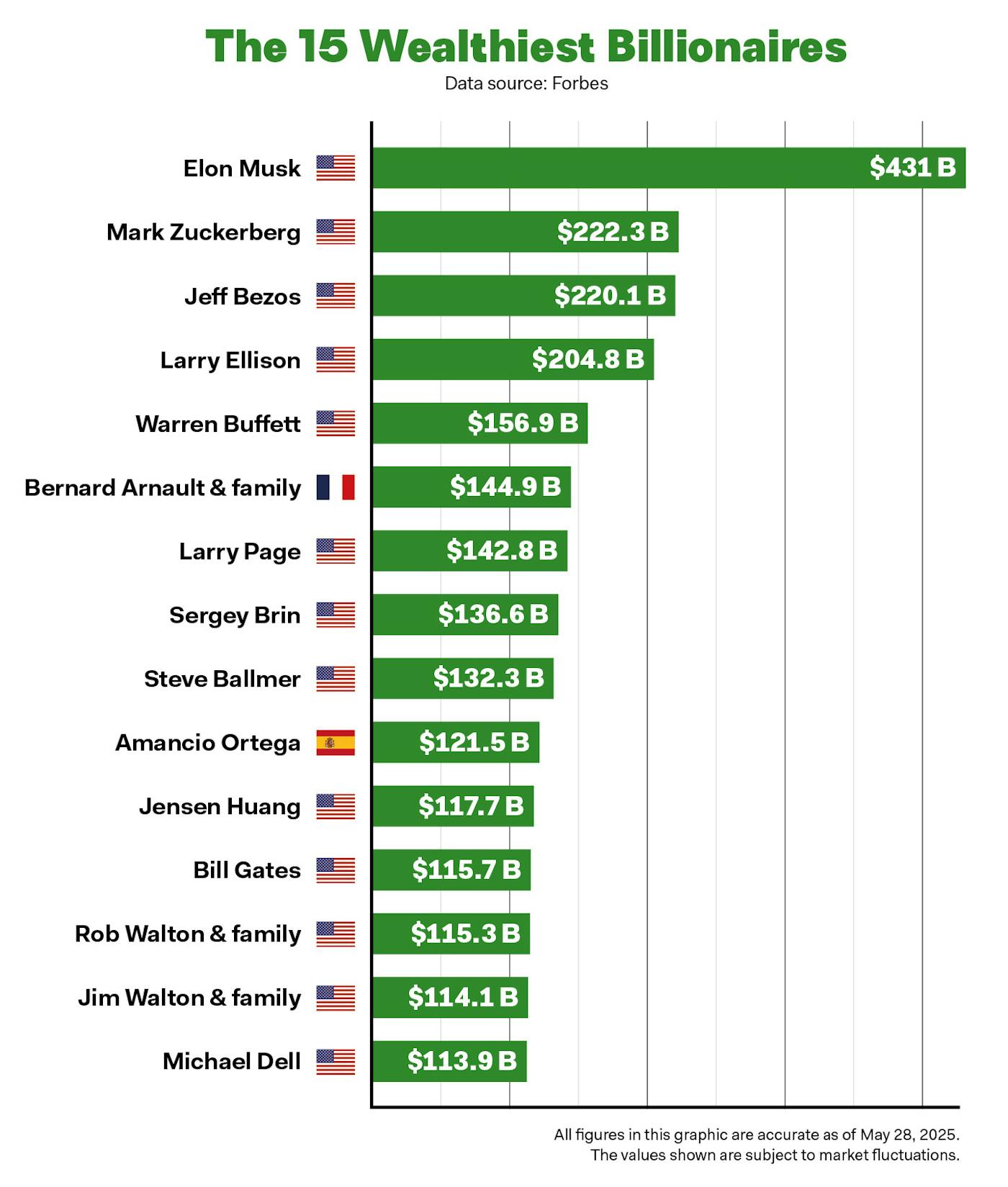

For his second term, Trump brought eight fellow billionaires into his administration, including “special government employee” Elon Musk, who is the richest person in the world (net worth as of May 28: $431 billion); Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick ($3 billion); Education Secretary Linda McMahon ($3 billion); Deputy Defense Secretary Stephen Feinberg ($5 billion); Ambassador-at-Large Steve Witkoff ($2 billion); and Small Business Administration Administrator Kelly Loeffler ($1 billion). Jared Isaacman ($2 billion) was nominated for NASA administrator but later withdrawn. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent is often described in news accounts as a billionaire, but his declared net worth is only about half a billion, and Bessent’s name does not appear on billionaire lists compiled and updated meticulously by Forbes and Bloomberg.

Add in two billionaire ambassadors, Arkansas banker Warren Stephens (U.K.) and Texas restaurant and casino tycoon Tilman Fertitta (Italy), and the combined wealth of the Trump Nine approaches $460 billion. Trump talks about buying Greenland from Denmark, but if the billionaires in Trump’s administration pooled their resources, they’d have enough to buy Denmark itself (GDP $450 billion). Neither Greenland nor Denmark is for sale, of course, because countries aren’t bought and sold. But it’s characteristic for billionaires to presume that everything is for sale. Including, now, the government of the United States. Which sort of is.

In his farewell address, President Joe Biden warned that “an oligarchy is taking shape in America of extreme wealth, power, and influence that literally threatens our entire democracy, our basic rights and freedoms, and a fair shot for everyone to get ahead.” Biden was talking about his successor, Trump, and he was right. No previous president brought in anywhere near so many billionaires as Trump—not even Trump himself during his first term.

The combined wealth of Biden’s Cabinet was $118 million, so obviously his administration was no haven for billionaires. The combined wealth of President Barack Obama’s Cabinet spiked to $2.8 billion during his second term, thanks to the presence of its sole billionaire, Commerce Secretary Penny Pritzker. Even Trump’s first-term Cabinet had only one confirmed billionaire, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos. But there were enough multi-millionaires like Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross to boost the Cabinet’s combined wealth to $6.2 billion—a record at that time, but nowhere near the $445 billion net worth possessed today by Trump’s Cabinet. When you exclude Musk (whose Department of Government Efficiency isn’t really a department, and who announced in late May that he was done with Washington), Trump’s Cabinet is worth $14 billion, still more than twice the combined net worth of Trump’s first-term Cabinet.

The price of admission isn’t cheap. The Trump Nine’s collective contribution to reelect Trump in 2024 (including donations to other Republicans) totaled about one-third of a billion dollars. The Trump Nine then lavished another $6 million on Trump’s inaugural, which raised $239 million, four times as much as Biden’s. The three biggest billionaire donors scored the three highest-ranking billionaire appointments: Musk ($291 million), Lutnick ($14 million), and McMahon ($12 million).

We’re in uncharted waters. “It’s tempting to liken this to the Gilded Age,” Michael Waldman, president of the nonprofit Brennan Center for Justice and a former speechwriter for Bill Clinton, told Elisabeth Bumiller of The New York Times in January. “But John D. Rockefeller didn’t actually run McKinley’s campaign or move into the White House.”

Waldman might have added that the Gilded Age never gave us a president who issued his own currency, as Trump has done no fewer than four times, or owned a majority stake in the private company (Truth Social) that informs the nation of his policies. At the end of Trump’s first term, the nonprofit Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, or CREW, tallied nearly 4,000 financial conflicts of interest. These continue to proliferate in Trump’s second term. There are Trump Bibles (Trump doesn’t attend church), Trump wine tumblers (Trump doesn’t drink), Trump key chains, Trump hoodies, Trump wrapping paper, Trump umbrellas, Trump golf balls, Trump beach towels, Trump sneakers, and Trump pajamas, most of these available at www.trumpstore.com. The proceeds go not to some campaign fund but to the Trump Organization, a privately held corporation owned by the president and run by his two oldest sons. Everything’s for sale.

Welcome to the American oligarchy. America always had rich people, and they always influenced government. But never before have the rich amassed money and power on anything like this scale, and Trump helped them get there. After Trump’s 2017 tax cut, the combined wealth of America’s billionaires doubled to $6 trillion, according to a July 2024 report by Americans for Tax Fairness. Going back to the start of the twenty-first century, American billionaire wealth increased ninefold. There aren’t enough billionaires in America to fill Carnegie Hall, but they own 3.8 percent of the nation’s wealth.

During that same quarter-century, the bottom half of the income distribution increased its collective wealth not ninefold but twofold (thanks largely to Covid stimulus checks). We’re talking about half the country—about 66 million families—owning not 3.8 percent of America’s wealth but 2.5 percent. By some measures, wealth concentration in America today is greater than in fourteenth-century Europe, even though America is democratic and fourteenth-century Europe was, you know, feudal. How did we arrive at so grotesque an imbalance of wealth? It didn’t happen overnight; more like half a century.

We’ll get to that. But first, let’s do some arithmetic.

II.

How Much Is One Billion?

In 1970, Hendrik Hertzberg, later editor of this magazine, published a charming book titled One Million. It was a visual guide intended to demonstrate what a very large number one million was. The book had 200 pages, each of which showed five thousand dots. For perspective, Hertzberg added two or three statistical notations per page (for example, “625,000—Separate bee-to-flower trips needed to produce a quarter of a pound of honey”). It’s a fun book to play with, but when Hertzberg updated it in 1993, he had to admit in an introduction that “in a world of five and a half billion souls, even a million can be a trifling quantity.” In 2025, we live in a world of eight billion souls.

Today most of us can conceptualize what it’s like to possess one million dollars, because odds are we know somebody who’s worth that much, at least on paper. The median price of a house in the United States is about $400,000, and in California, the nation’s most populous state, it’s getting close to one million ($866,100). Taking out a mortgage on a house in California is apt to make you a millionaire.

Have you ever had surgery? Your typical surgeon, unless just starting out, probably has a net worth of $1 million or more, because median annual pay for surgeons exceeds one-quarter of a million dollars. All told, about 24 million households possess $1 million or more in assets. That’s about 18 percent of the population. As far back as 1996, two personal-finance writers titled a bestseller The Millionaire Next Door to convey that millionaires, though wealthy, were no longer the exotic species they once were.

Nobody would title a personal-finance book The Billionaire Next Door, because billionaires are an exotic species. Consider the difference between one million of anything and one billion. It isn’t just the next large number. It’s the next large number by a factor of one thousand. A Hertzberg-like visual guide titled One Billion could never be published, because it would have to be 200,000 pages long.

The word “billion” didn’t even possess a settled English-language meaning until half a century ago; before that, Britons, following the French, used “billion” to describe one million millions, while Americans called that one trillion and defined “billion” as one thousand millions. Tiring of the discrepancy, Prime Minister Harold Wilson altered the definition in 1974 to conform to American English. (To this day, the French insist on calling one trillion un billion and one billion un milliard.) Before 1900, no consistent Anglophone definition was especially necessary, because one seldom encountered one thousand million of anything.

That started to change in 1916, when newspapers declared the Standard Oil baron John D. Rockefeller the world’s first billionaire. (In fact, Rockefeller’s wealth topped out at $900 million, according to his biographer Ron Chernow, making the likely first billionaire Henry Ford a decade or so later.) At midcentury, the following joke about federal spending was attributed to Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirksen, an Illinois Republican and fiscal conservative: “A billion here, a billion there, and pretty soon you’re talking real money.” Dirksen’s point, if he said it (he probably didn’t), was that one billion was a very large number, and that the government should be less casual about spending such vast sums.

Dirksen was right that one billion is a far bigger number than we typically appreciate. Let’s say you wanted to count out loud to one million at a rate of one number per second, never taking any breaks. (I don’t recommend this.) There being 86,400 seconds in a day, you’d be done in 11 and a half days. A guy in Birmingham, Alabama, named Jeremy Harper did something like this in 2007, according to Guinness World Records, only he took breaks. Counting into a webcam every day, Harper got to one million in 89 days.

To own $1 billion is to possess more dollars than you’ll ever count. It’s to possess more dollars than any human being will ever count. And Forbes counts 15 Americans who possess hundreds of billions.

But Jeremy Harper will never count out loud to one billion. Nobody will, because instead of 11 and a half days, or even 89 of them, counting to a billion with no stopping to eat or sleep would take 31 years and eight months. If you worked at Harper’s pace, taking breaks every day, it would take more than 244 years, which is twice the longest human lifespan ever recorded. To own $1 billion is to possess more dollars than you’ll ever count. It’s to possess more dollars than any human being will ever count. And that’s just one billion. Forbes counts 15 Americans who possess hundreds of billions.

Don’t feel bad if you’ve never met a billionaire. According to JPMorgan Chase, there are not quite 2,000 of them in the entire country. But they’ve proliferated with amazing speed over the past 40 years, and especially in the last five.

In 1957, there were one or perhaps two billionaires in the United States. Fortune pronounced the California oilman J. Paul Getty the richest man in the United States, with a net worth estimated between $700 million and $1 billion; Getty himself wasn’t sure (“I just don’t know the exact total”). The New York Times then chimed in that, no, the richest man in the United States was the Texas oilman H.L. Hunt, with an estimated net wealth in excess of $2 billion. Hunt was also, per the Times, the only one of the world’s five richest people who was American; most of the others were Mideast potentates. To make Fortune’s 1957 list of “Super Rich” Americans, all you needed was $50 million (about $580 million in current dollars).

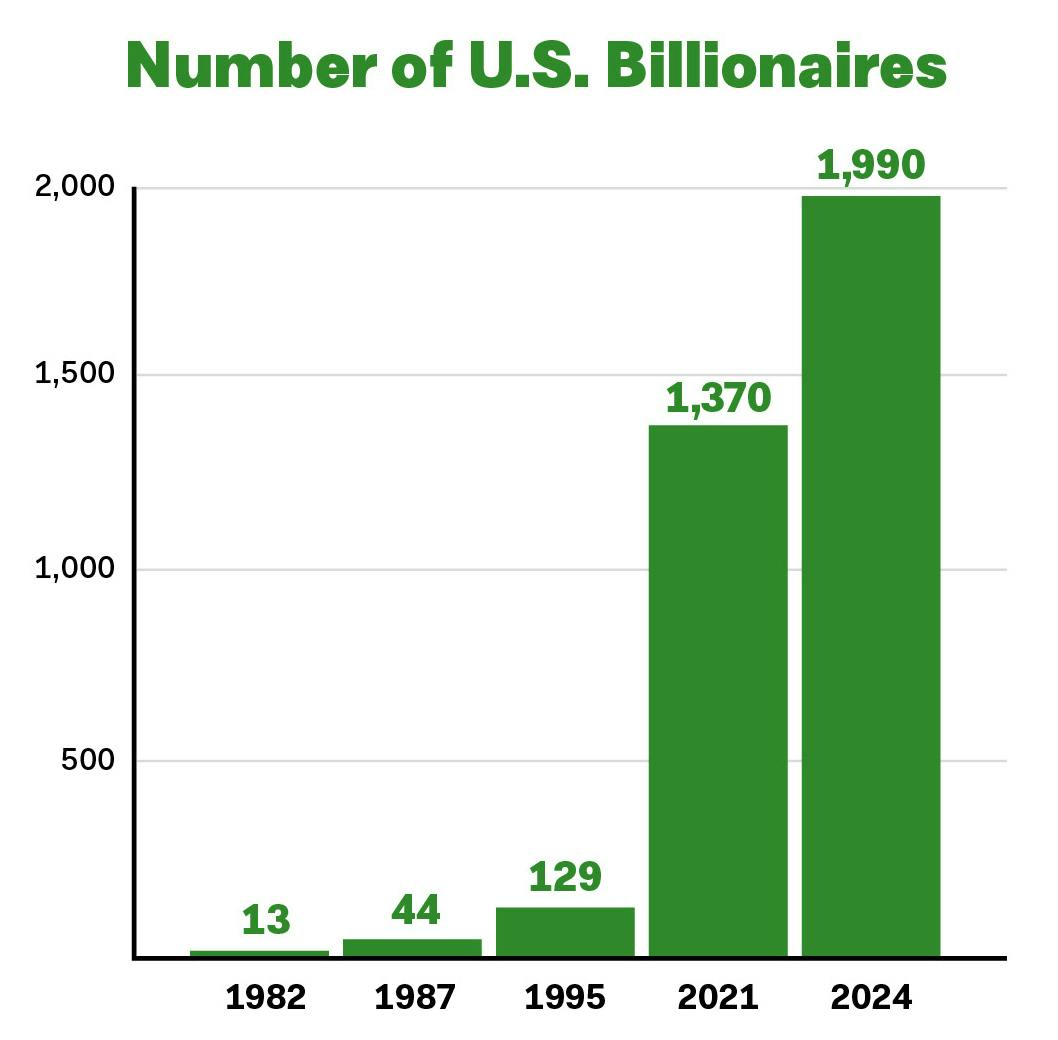

In 1982, when Forbes initiated its annual list of the 400 wealthiest Americans, it counted 13 billionaires, and, to make the list, your net worth had to be $100 million (about $340 million in current dollars). In 1987, Forbes counted 44 American billionaires. By 1995, it counted 129. That was the first year Forbes identified two Americans (Bill Gates and Warren Buffett) as the world’s two richest people. By 2021, there were 1,370 American billionaires, according to JPMorgan Chase, and over the next three years their number increased by a stunning 45 percent, to 1,990. Today, Americans dominate the Forbes billionaire list. In 2025, only two out of the top 15 are foreigners: France’s Bernard Arnault (cosmetics) and Spain’s Amancio Ortega (fashion).

The world has so many billionaires now that we’re starting to read about growing inequality among billionaires. “In 2015,” Swiss bank UBS reported last year, “the 100 wealthiest billionaires represented 32.4% of all billionaire wealth. Compare that to 2024, when the top 100 accounted for 36%.” In April, The Wall Street Journal’s Juliet Chung, drawing on data from Berkeley economist Gabriel Zucman, reported that America’s top 0.00001 percent—a group today consisting of 19 families whose wealth exceeds $45 billion—expanded its share of the nation’s wealth from 0.1 percent in 1982 to 1.8 percent in 2024. These 19 families, which include Musk, Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg, Bill Gates, and Warren Buffett, expanded their collective wealth last year by $1 trillion.

The threshold to be the world’s richest human keeps rising. In 1976, the year Getty died, he was the world’s richest, with a net worth of $6 billion. Eleven years later, in 1987, you needed $20 billion to be the world’s richest (Yoshiaki Tsutsumi, Japanese investor). In 1997, you needed $36 billion (Bill Gates). In 2007, you needed $56 billion (still Gates). In 2017, you needed $86 billion (still Gates). In 2018, Jeff Bezos seized the title, with $112 billion. Four years later, in 2022, Musk moved into the top spot, with $219 billion. Now he holds the top spot, with $431 billion.

You’re thinking: Maybe it’s inflation. It’s not inflation. Here’s that progression in constant 2023 dollars: $32 billion (Getty), $54 billion (Tsutsumi), $69 billion (Gates), $82 billion (Gates), $107 billion (Gates), $136 billion (Bezos), $228 billion (Musk). And $402 billion (Musk).

Before you know it, it will take $1 trillion to be capo di tutti capi. Barring a global financial catastrophe (an ever-present danger under Trump), the world will likely see the first trillionaire within the next decade. This person will probably be American. Today’s leading contender, I’m sorry to report, is Musk. Whoever it is, this person will own a quantity of dollars that, if you counted one numeral per second and never, ever stopped, would take you … let’s see. Yes, nearly 32,000 years.

III.

What Do Billionaires Want?

Over the past half-century, American billionaires have graduated from being a curiosity to being an identifiable class. It is now possible to ask: What do billionaires want?

Money, obviously. The mansion, the yacht, the private plane, the butler, the personal chef, personal security. Last year, the writer Sylvie Tremblay added up these and other expenses for Yahoo Finance and calculated the billionaire lifestyle costs about $67 million per year. That’s a lot to you and me, but not to a billionaire, whose investments probably throw off at least that much per year. Even if you took $1 billion and put it in a savings account that paid 5 percent interest (I don’t recommend this), you’d get back $50 million in 12 months. In the real world, billionaire investments outperform the stock market. I mentioned already that you can’t count to one billion. You can’t spend $1 billion either. It’s not that easy to spend even $100 million.

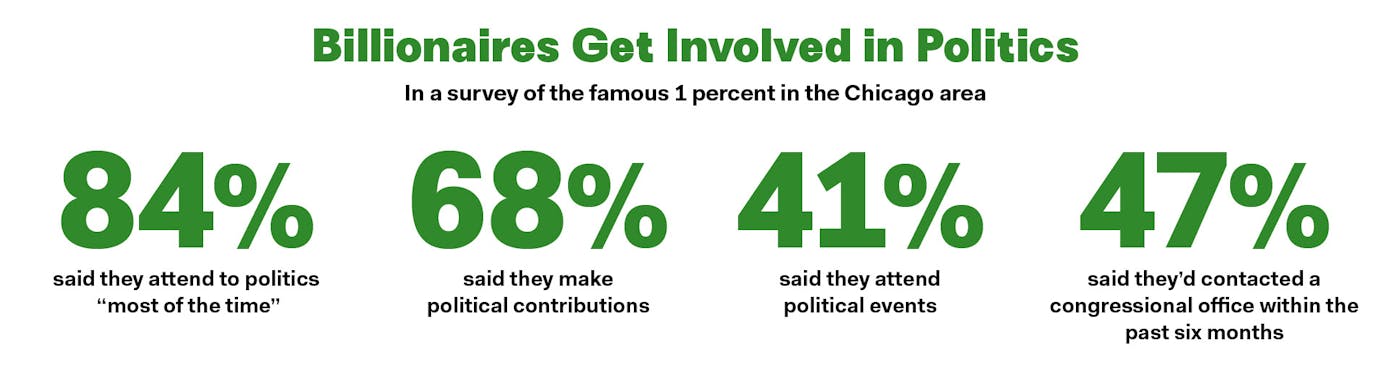

So billionaires get involved in politics. In a 2013 survey of the famous one percent in the Chicago area, the political scientist Larry Bartels of Vanderbilt, along with Benjamin Page and Jason Seawright of Northwestern, found that 84 percent said they attended to politics “most of the time,” 68 percent said they made political contributions, and 41 percent said they attended political events. The one percent encompass more than billionaires, of course, but the wealth of the sample averaged $14 million, which is very rich.

Nearly half of these one-percenters—47 percent—said they’d contacted a congressional office within the past six months; contacts with executive branch officials were also common. Asked why they contacted government officials, about 44 percent acknowledged it to be a matter of “fairly narrow economic self interest.” The authors noted that, “given possible sensitivities about such contacts, it is possible that their frequency was underreported.” Striking differences were noted between the political views of the rich and those of everybody else. Queried about policy preferences, only 43 percent of the one-percenters agreed that “Government must see that no one is without food, clothing, or shelter,” compared to 68 percent of the general public. The rich were much less keen than the general public on government regulation and favored a top marginal rate of 34.2 percent and a top capital gains rate of 17.3 percent. At the time, these were 39.6 percent and 20 percent.

In a follow-up paper in 2014, Page and Seawright zeroed in on billionaires. Noting that previous studies showed political influence to be proportionate to wealth, they calculated, in a manner they admitted to be speculative, that each member of the Forbes 400 exerted 59,619 times as much political influence as the average member of the bottom 90 percent in income distribution. If that’s even roughly true, then America has been an oligarchy for some time. Given billionaires’ rabbitlike proliferation since 2014, it should hardly surprise us that so many of them are opting for hands-on experience in our billionaire president’s government.

IV.

What Is Oligarchy?

The word “oligarchy” means literally “government by the few,” where “the few,” at least as far back as Aristotle, has been understood to mean “the rich.” Functionally, “oligarchy” usually carries the same meaning as “aristocracy,” only minus any quaint notion that an aristocracy will govern disinterestedly, placing the nation’s interests above its own. In those countries where wealth grows more concentrated among the few, as has occurred in the United States over the past half-century, governments incline toward oligarchy.

The threat that American democracy would devolve into an oligarchy was present from the beginning. Before the Constitution’s ratification, 11 of the 13 colonies abolished primogeniture, or the inheritance of an estate by the oldest son. The other two colonies (Rhode Island and South Carolina) abolished it soon after. The European aristocracy used primogeniture to preserve and expand wealth across generations, a system that held particular appeal in the American South, where a plantation economy had already taken hold (and where something like oligarchy would prevail through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries). But in 1785 Thomas Jefferson sponsored a bill in the Virginia Legislature to abolish primogeniture, and other Southern states followed suit—in Jefferson’s words, laying “the axe to the root of Pseudoaristocracy.” In much the same spirit, Jefferson had earlier gotten the Virginia Legislature to abolish the entail, a legal prohibition against a spendthrift heir selling off the family estate, and several other colonies followed suit on that as well. Another preventive measure was Article I, Section 9, Clause 8, of the Constitution: “No Title of Nobility shall be granted by the United States,” nor accepted from a foreign government by any government official.

John Adams was the Founder who fretted most about oligarchy. In Adams’s view, a strong executive was the most effective bulwark against government serving only the interests of the wealthy. “You are afraid of the one,” Adams famously wrote Thomas Jefferson a few months after the Constitutional Convention. “I, of the few.… You are apprehensive of monarchy; I, of aristocracy.” The political scientist Luke Mayville, in his 2016 book, John Adams and the Fear of American Oligarchy, explains this difference. Jefferson, writes Mayville, believed that “Old World aristocracies would be replaced in the republican age by new natural aristocracies of virtue and talent.” Adams, on the other hand, believed (per Mayville) that “wealth and family name would continue to overpower virtue and talent.” Both men would prove right up to a point, but Adams was better able to perceive that the moneyed classes would never cease to represent a threat.

The lexicographer Noah Webster shared Adams’s fear of “the few.” Webster judged governments in Europe not so much monarchies as “aristocratic republics” (italics his), wherein “The barons, who possess the lands, have most of the power in their own hands.” Consequently, Webster concluded (writing in 1790) that “the basis of a democratic and a republican form of government” was “an equal or rather a general distribution of property.” Laws restricting multigenerational wealth, Webster wrote, “hold out to all men equal motives to vigilance and industry. They excite emulation, by giving every citizen an equal chance of being rich and respectable.”

Opposition to oligarchy was a significant motivating factor in the creation of the Democratic Party. “To be allied to power, permanent, if possible, in its character and splendid in its appendages, is one of the strongest passions which wealth inspires,” wrote the modern party’s founder (also the nation’s eighth president), Martin Van Buren. Van Buren saw the moneyed classes in “constant struggle for the establishment of a moneyed oligarchy,” a battle that in Van Buren’s time was perceived to play out over the Second Bank of the United States, which President Andrew Jackson shut down. Resistance to oligarchy, the law professors Joseph Fishkin of UCLA and William E. Forbath of the University of Texas observe in The Anti-Oligarchy Constitution (2022), also motivated Reconstruction, creation of the income tax, and labor law. “We must make our choice,” said the Supreme Court Justice and antitrust champion Louis Brandeis. “We may have democracy, or we may have wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can’t have both.”

V.

The Gilded Age and the Roaring ’20s

Prior to our current era, the most oligarchical period in American history was the half-century after the Civil War. Distribution of wealth grew more unequal from the Gilded Age (1870–1900) to the Progressive Era (1900–1917), then grew again in the 1920s. According to a 2005 paper by economists Joshua Rosenbloom of Iowa State and Gregory Stutes of Minnesota State, the top one percent’s share of the nation’s wealth grew from about 28 percent in 1870 to about 40 percent in 1916.

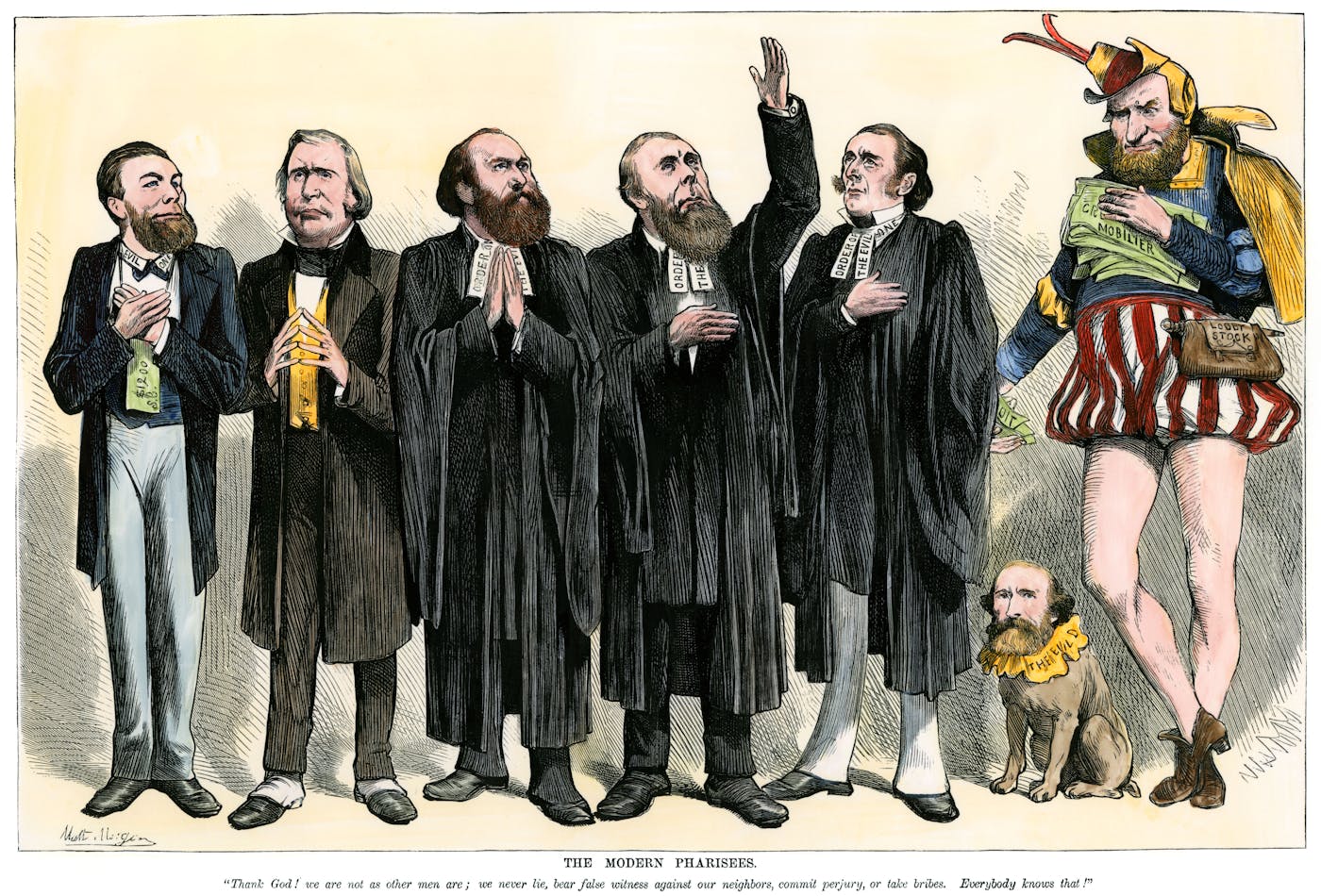

Not coincidentally, the Gilded Age was, at all levels of government, the most spectacularly corrupt period in American history—worse even than today (though Trump is gaining fast). Among the most infamous episodes was the Crédit Mobilier scandal, organized by a Union Pacific Railroad vice president named Thomas Durant. Durant set up a fake company named after a real French bank and used it to divert congressional subsidies meant for railroad construction. To keep Congress quiet, he distributed shares to various members, including Schuyler Colfax (speaker of the House and subsequently vice president to President Ulysses Grant).

As Crédit Mobilier demonstrated, it wasn’t necessary for oligarchs to enter government to work their will; instead, they could simply buy it. Especially prior to elimination of the spoils system (which Trump is trying to revive) with the Pendleton Civil Service Act of 1883, Washington was a sewer. A despairing civil servant named Julius Bing wrote of the federal government in 1868, “There is no organization save that of corruption; no system save that of chaos; no test of integrity save that of partisanship; no test of qualification save that of intrigue.”

The railroad robber baron Collis P. Huntington didn’t disagree. As he explained in an 1877 letter: “If you have to pay money to have the right thing done, it is only just and fair to do it.… If a man has the power to do great evil and won’t do right unless he is bribed to do it,” then “it’s a man’s duty” to extend the bribe. Eventually, though, so many other oligarchs followed Huntington’s logic that he complained the sum necessary “to fix things” was inflated outrageously. “I am fearful this damnation Congress will kill me,” Huntington despaired as the price of owning a congressman approached $500,000.

Wealth flocked to Washington, the journalist Jack Shafer observed in 2021, building Gilded Age mansions not far from where Bezos, Zuckerberg, Peter Thiel, Eric Schmidt, and Trump’s part-time crypto czar David Sacks would acquire properties a century and a half later. (Musk reportedly preferred to sleep at the office.) “Mine owners, old family money, publishers, railroad money and plantation proprietors charged into the city,” wrote Shafer in Politico,

purchasing large plots of land that radiated out of the hub that was Dupont Circle and erected costly, showy, status-proclaiming mansions on the neighborhood’s broad streets…. Where there weren’t outright government concessions and contracts to be won, there were laws, policies and treaties that could be fashioned to the economic advantage of a plutocrat.

Many of these handsome structures, now converted to office space or diplomatic missions, remain familiar Dupont Circle landmarks today.

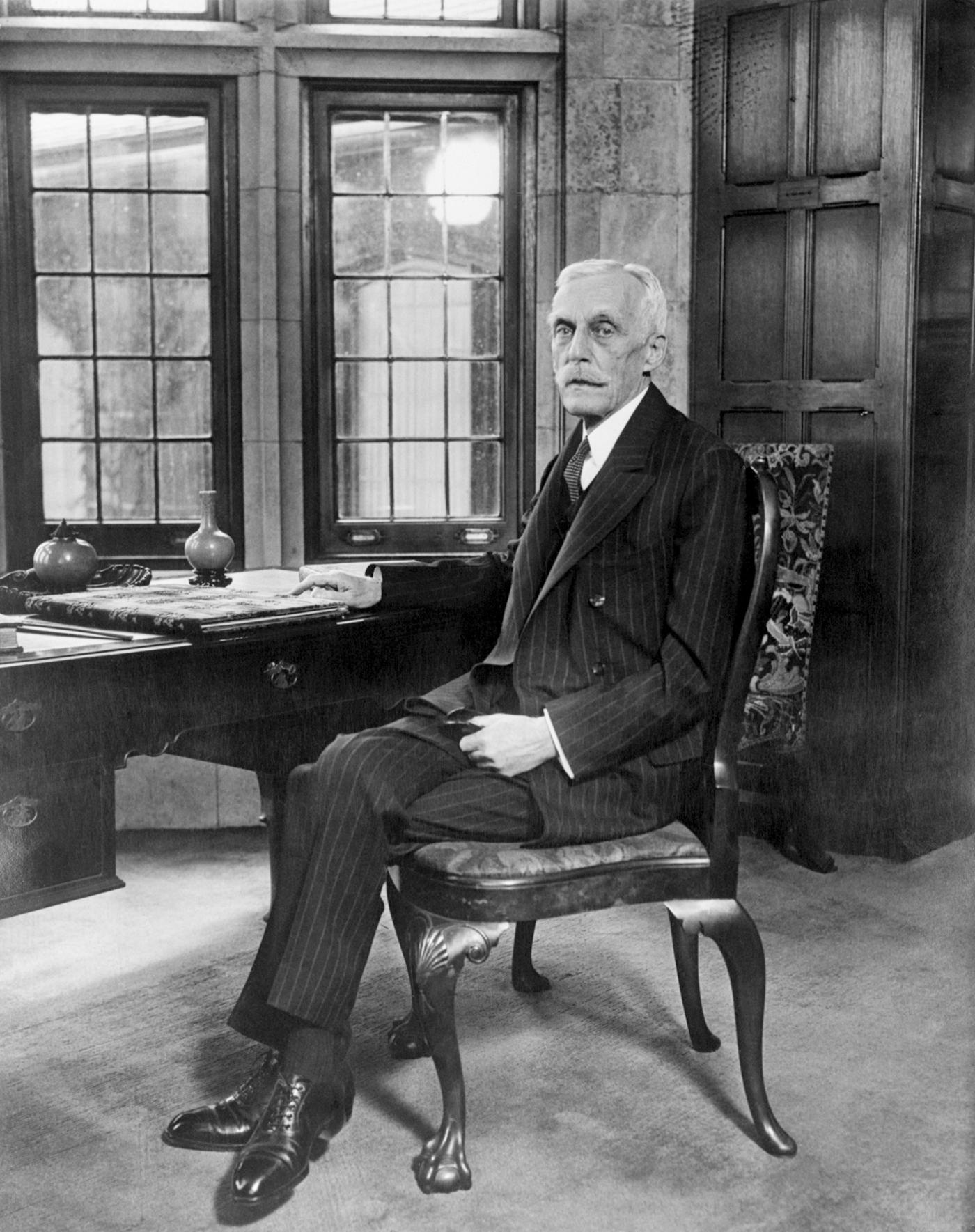

Andrew Mellon did the Gilded Age oligarchs one better. His innovation was to eliminate the middleman and take a government job himself—in Mellon’s case, as treasury secretary—much as Trump would do a century later. Though not a billionaire in his own time, Mellon was probably the third-richest person in America (after Rockefeller and Ford), with a net worth that peaked in 1930 at around $350 million—$7 billion in today’s dollars. Unlike Trump, Mellon was a cultivated man around whose personal art collection he built Washington’s National Gallery. But in most important ways, Mellon was a Trump-style oligarch avant la lettre.

Like Trump, Mellon was a nepo baby who made good. On graduating from the Western University of Pennsylvania in 1873, Mellon went to work for his Irish-born father, Thomas, in Pittsburgh at the aptly named T. Mellon and Sons (later known as the Mellon Bank). Within eight years, Thomas would recall gratefully, Andrew was “able to take the entire management of it upon himself.” Mellon fils greatly expanded bank operations, helping to create the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa), Gulf Oil, and Union Steel, which later merged with U.S. Steel. In 1921, President Warren G. Harding named Mellon treasury secretary. As with Elon Musk a century later, Mellon’s nomination rewarded a huge transfusion of campaign cash—in Mellon’s case, a loan to Harding’s campaign of $1.5 million ($25 million in current dollars).

Mellon’s great project as treasury secretary under Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover was to lower taxes. During World War I, the top marginal income tax rate had shot up to 77 percent on income above $1 million ($23 million in current dollars), and when Mellon assumed office, it was still 73 percent. Mellon dropped that to 25 percent. He still paid about a million per year in taxes, but as Mellon biographer David Cannadine points out, he ought to have paid much more, because “Mellon’s income more than doubled in these years.”

Meanwhile, Cannadine observes, repeal of a 25 percent gift tax in 1926 (Mellon also halved the estate tax to 20 percent) “made it possible for Mellon himself to begin transferring his immense holdings to his children, and toward the end of the decade, he would begin to make such untaxed gifts in increasing amounts.” The Mellon fortune was intact enough a century later (about $14 billion, per Forbes) to allow Andrew’s grandson Timothy—a financier who complained in a 2015 memoir that the Great Society made Black people “even more belligerent”—to become the Republicans’ second-biggest donor (after Musk) in the 2024 election, giving $197 million.

It was Andrew Mellon who pioneered the favored Trump abuse of siccing the Internal Revenue Service (then called the Bureau of Internal Revenue) on his enemies. The enemy in this instance was Senator James Couzens, a Michigan Republican who previously had been a vice president at Ford and reputedly was the richest man in Congress. Couzens had infuriated Mellon by initiating a congressional investigation of the tax agency that risked exposing tax underpayments by Mellon companies. Mellon retaliated by directing the Bureau of Internal Revenue to investigate possible tax underpayment in Couzens’s sale some years earlier of Ford stock to Henry Ford. The investigation concluded that Couzens owed $11 million in taxes (though a Board of Tax Appeals created by Mellon himself would later conclude that Couzens was actually owed a $900,000 refund).

Also like Trump, Mellon was a tariff advocate. As treasury secretary, Mellon helped secure tariff protection for Alcoa that, a New Republic editorial observed in 1926, “enabled it to raise the prices of its product.” Unlike Hoover, Mellon was untroubled by the 1930 Smoot-Hawley tariff that plunged the country deeper into the Great Depression. Perhaps because his own net worth was at its zenith, Mellon remained oblivious to the prospect of a sustained economic downturn. As late as May 1931, Mellon was telling the American Bankers Association that “conditions today are neither so critical nor so unprecedented as to justify a lack of faith in our capacity to deal with them in our accustomed way.” This was, Mellon said, “no time to undertake drastic experiments.” His son, Paul, would recall seeing the following graffito on a gas-station urinal around that time:

Mellon pulled the whistle,Hoover rang the bell,Wall Street gave the signal,And the country went to hell.

Representative Wright Patman, a populist Texas Democrat, initiated impeachment proceedings against Mellon, prompting Hoover to move Mellon from Treasury to the U.S. Embassy in London. There, Mellon persuaded the British foreign office to allow Gulf Oil, in which he owned a majority stake, to drill in Kuwait. Mellon died in disgrace five years later, fending off tax investigations by the Roosevelt administration.

Mellon was in many ways a more upstanding citizen than Trump, and certainly a more competent businessman. But the lesson of his career in government is largely the same: Fantastically wealthy people who remain active participants in the economy have no place in government. As The New Republic put in 1926, Mellon was

too preposterously rich to occupy with public credit the position of Secretary of the Treasury…. Whenever public business is entrusted to a man with conspicuous and enormous private interests, the discussion of most questions of public policy, which his work involves, is confused by irrepressible and distracting personal considerations.

The same sentence could have been written last week, substituting “president” or “DOGE leader” for “treasury secretary.” The voting public heeded this lesson from the Great Depression through the early 1970s. Then it proceeded to forget it.

VI.

The Oligarchs’ Waterloo

The Great Depression cured America of empowering oligarchs. President Franklin Roosevelt, though himself a beneficiary of inherited wealth (his net worth at death was $1.9 million), was at worst a benign oligarch. More to the point, he is generally agreed, after Abraham Lincoln, to be the second-greatest president in American history. Roosevelt relished being called a traitor to his class. He condemned “economic royalists” who, “thirsting for power, reached out for control over government itself.” He said that the 1929 crash “showed up the despotism for what it was,” and that his election in 1932 “was the people’s mandate to end it.” Roosevelt required the oligarch class to pay minimum wage, give employees a 40-hour workweek, and recognize labor unions, among other regulatory measures, and he increased the top marginal tax on income above $1 million from 25 percent to 63 percent. Later Roosevelt raised the top marginal rate to 79 percent for income above $5 million, and during World War II he raised the top rate to 94 percent, dropping the threshold to $200,000 ($3.7 million in current dollars). The top threshold remained above 90 percent most years until the mid-1960s, when it dropped to 70 percent most years until 1982.

Great fortunes continued to be built—among those who created or expanded their fortunes during the Depression were Getty, Howard Hughes, and Joseph Kennedy. But the political influence of would-be oligarchs diminished. The exception was the benign oligarch Kennedy, whom FDR appointed chair of the newly created Securities and Exchange Commission in 1934. Though credited with getting the agency up and running, Kennedy “stepped down before newer, tougher regulation went into effect,” according to an official SEC history. Kennedy then wrote (with uncredited help from New York Times columnist Arthur Krock) a book titled I’m for Roosevelt for the 1936 campaign, in which Kennedy sought to reassure his fellow business leaders that “the New Deal is founded upon a basic belief in the efficacy of the capitalistic system,” and that “no civilized community ever existed without restraints.” The oligarchs didn’t buy it, but Roosevelt won a landslide reelection anyway. In 1937, Roosevelt named Kennedy ambassador to London, and Kennedy proceeded to end all prospects of a continued career in government by opposing U.S. entry into World War II. This was partly because Kennedy feared “the loss of foreign trade that’s going to threaten to change our form of government.” His net worth at the time of his death in 1969 was about half a billion.

Joe Kennedy’s oligarchical legacy was his children, three of whom became senators and one, John F. Kennedy, president. To varying degrees, all three followed the FDR model of playing traitor to their class. But we shouldn’t overlook that John F. Kennedy successfully championed lowering the top marginal tax rate from 91 to 70 percent (signed into law by Lyndon Johnson after JFK’s assassination); that Robert Kennedy prosecuted the (outrageously corrupt) Teamsters president Jimmy Hoffa, bitter enemy of the Chamber of Commerce; and that some years later, Edward Kennedy helped push through deregulation of trucking and airlines (policies that, to be sure, were supported at the time by other liberals in good standing like Ralph Nader). In joining Trump’s billionaire-dominated administration, the patriarch’s grandchild, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., might be said finally to uphold the family’s class interest. But Bobby Jr. is a uniquely hard case, personally opposing both big business and the public interest in his crackpot crusade against vaccination.

One hopes that the billionaire Illinois Governor Jay Pritzker, who’s running unofficially for the Democratic nomination in 2028, will also play traitor to his class, but be prepared for surprises. His sister Penny, along with two other Chicago billionaires, helped persuade Obama not to support a pro-union “card check” bill that was a forerunner to today’s Protecting the Right to Organize Act. Pritzker is as yet undeclared on whether he supports the PRO Act. If he never endorses it, that will tell us a lot.

From the 1930s through most of the 1970s, American government remained oligarch-unfriendly. Where economic inequality had flourished under Mellon, it shriveled after he left government. Instead, incomes either grew more equal or, at worst, grew no more unequal. Income share for the top 10 percent, which had risen to nearly 50 percent under Mellon, fell to 35 percent or less under Roosevelt and his successors until 1979 (when it started climbing again). Gross inequalities based on race and gender persisted, of course, financial and otherwise, but wages were converging. The economist Simon Kuznets of Johns Hopkins attributed this to “the dynamism of a growing and free economic society.” The oligarchs were dethroned. The Nobel Prize–winning economist Claudia Goldin of Harvard and Robert Margo of Boston University called this “the Great Compression.”

VII.

The Great Forgetting

It didn’t last. In a 2012 book, I call the period that followed the Great Compression, which persists to this day, the Great Divergence. (I borrowed the play on Goldin and Margo’s phrase from Paul Krugman.) I might also have called this period the Great Forgetting. As memories of the Great Depression faded, New Deal regulations limiting risk in the banking sector and other industries melted away; support for labor unions dwindled; antitrust prosecution grew less ambitious; minimum wage increases grew more infrequent; stock buybacks, previously banned as a form of stock manipulation, were made legal; and taxes on the rich grew less onerous.

Much of the impetus for the Great Forgetting, University of Arizona historian David N. Gibbs reports in his 2024 book Revolt of the Rich, was corporate dissatisfaction with its own performance amid spiraling inflation and rising global competition. “Is the Rate of Profit Falling?” asked a 1977 paper by Harvard’s Martin Feldstein and a 22-year-old wunderkind named Lawrence Summers. Yes, it was. The annual rate on return of nonfinancial capital, they found, had dwindled from 10–13 percent in the 1950s and 1960s to an average of 7.9 percent in the 1970s. In 1975, William Simon, treasury secretary for President Gerald Ford, complained that capital formation in the United States was “the lowest of any major industrialized country in the free world.”

Rather than blame themselves—rich people are famously terrible at that—or even the unique economic disruption from President Richard Nixon’s taking the United States off the gold standard in 1971 and the Arab oil embargo in 1973—the business community blamed ascendant liberals and the left. And not just businesspeople. Journalists got into the act, too. In 1974, Gibbs reports in Revolt of the Rich, Business Week advised that many Americans would have to “accept the idea of doing with less so that big business can have more.” The following year, the respected economist Arthur Okun, who’d been President Johnson’s chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, gave a series of lectures at Harvard that argued economic equality and economic efficiency were in conflict; increase one, and you’d decrease the other. (Not a lot of people believe this anymore.)

Such sentiments fell on well-tilled soil. Nixon, whose White House famously once proposed firebombing the Brookings Institution, was, Gibbs writes, actively raising money to elevate the profile of a backwater pro-business think tank called the American Enterprise Institute, which had attracted little attention since its founding during the New Deal. By 1971, Charles Colson, who led the effort with fellow White House staffer Bryce Harlow, could boast in a memo, “we have now more than doubled their operating budget,” and “they are taking on a number of assignments that are very important to us.” Harlow had spent the previous several years playing Johnny Appleseed for the nascent corporate lobby, traveling the country to urge big business to be more aggressive in defending its interests. Lewis Powell did the same in 1971, shortly before he went on the Supreme Court, in a memo to the Chamber of Commerce that complained “the American economic system is under broad attack” from “Communists, New Leftists and other revolutionaries,” by which he meant, principally, Ralph Nader. Barron’s editor Robert Bleiberg seconded this in 1972: “Perhaps the most downtrodden and persecuted of all American minorities [is] corporate enterprise…. Isn’t it about time that investors began to fight back?”

Oligarchs bankrolled this counteroffensive. Among those whom the White House solicited for assistance building AEI was the oligarch Richard Mellon Scaife, grandnephew of Andrew Mellon, from whose fortune Scaife inherited more than $500 million. (Scaife would die a billionaire in 2014.) Scaife was Nixon’s second-largest fundraiser in 1972 and would later provide crucial seed money to the Heritage Foundation and the Manhattan Institute. Still later, Scaife would bankroll smear campaigns against Bill and Hillary Clinton. Scaife was no one’s idea of a benevolent philanthropist; asked in 1981 by a female reporter why he contributed so much money to the New Right, he replied, “You fucking communist cunt, get out of here.”

Others who funded right-wing nonprofits included the billionaire oligarchs Joseph Coors and Charles Koch, along with assorted oligarch-funded organizations including the John M. Olin Foundation and the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation. “Enormously wealthy right-wing donors,” wrote the journalist Jane Mayer in her 2016 book, Dark Money, “transformed themselves from the ridiculed, self-serving ‘economic royalists’ of FDR’s day into the respected ‘other side’ of a two-sided debate.”

The foundations, Mayer observed, constituted a “weaponizing” of traditional philanthropy. The Olin Foundation began life in 1953 as a conventional, paternalistic organization that gave money to museums and hospitals. Its funder, John Olin, was former president of the Olin Corporation, a privately held conglomerate founded in 1894 by his father, Franklin, that owed much of its prosperity to government contracts during two world wars. Fortune’s “Super Rich” list of 1957 ranked Olin and his brother Spencer the thirty-fifth wealthiest Americans, with a combined net worth of more than $75 million (about $870 million in today’s dollars).

Olin was radicalized in 1972 when the Environmental Protection Agency, created just two years earlier, issued regulations tightening production of the pesticide DDT, of which the Olin Corporation controlled 20 percent of the American market. The Olin Corporation was also targeted for dumping mercury into the Niagara River and other waterways. “My greatest ambition now,” Olin said in a 1977 interview, “is to see free enterprise re-established in this country. Business and the public must be awakened to the creeping stranglehold that socialism has gained here since World War II.” That same year, Olin hired Ford’s bomb-throwing Treasury Secretary William Simon to be president of the Olin Foundation, where he worked to create a conservative “counter-intelligentsia.”

The billionaire counteroffensive was further torqued by a series of Supreme Court decisions loosening restrictions on campaign finance by equating money with speech. These began with Buckley v. Valeo (1976), which ruled that government-mandated restrictions on campaign spending, including by independent committees and a candidate’s own funds, violated the First Amendment. The culminating decision was Citizens United (2010). That ruling is remembered as eliminating a 117-year prohibition on political campaign spending by corporations. But publicly held corporations of the type that dominate the S&P 500, and with which we’re most familiar, don’t typically want to spend on campaigns (apart from company political action committees, where contributions are limited and come technically from individual employees). Public corporations shun such activity because they don’t want to rile stockholders.

What Citizens United really did was open the floodgates to campaign spending by private corporations, which is to say companies owned by oligarchs. It was the billionaires’ Magna Carta. The ruling eliminated virtually all restrictions on independent campaign expenditures, based on the presumption that these weren’t coordinated with political candidates. (That this presumption was wrong was plainly obvious to anybody who was paying attention.) The ruling begat Super PACs, which (unlike regular PACs) could accept and give unlimited amounts, and “dark money” 501(c)(4)s—ostensible “social welfare” nonprofits, which allowed billionaire “philanthropists” to spend unlimited funds directly on political campaigns, with only slightly more restrictions, without disclosing their source. Meanwhile, for unrelated reasons, the number of publicly held corporations—the type that, Citizens United be damned, didn’t like giving to political candidates—shrank during this period by nearly half, from about 7,000 in 1996 to about 4,000 in 2020. In that sense, capitalism itself was getting less democratic and more hostage to the whims of oligarchs and their privately held companies.

In 2024, Citizens United enabled Trump to treat his official campaign as an afterthought and to focus fundraising efforts on Super PACs that Citizens United presumed he wouldn’t control, but did. About 44 percent of all the funds that supported Trump in 2024 came from 10 individual donors. Although Kamala Harris outspent Trump overall (demonstrating that money isn’t everything), of the top 10 donors to either candidacy—the bulk of it to outside groups—seven supported Trump. Harris won the money race, but Trump won the billionaire oligarch race.

But now I’m getting ahead of our story.

VIII.

The Reagan Reversal

In retrospect, the oligarchs eliminated the New Deal consensus with astonishing speed. Setting Nixon’s 1968 election as the starting gun and Ronald Reagan’s 1980 election as the finish line, it was the work of a dozen years. This was all the more remarkable, given the major setback of Watergate, which gave Democrats enormous congressional gains in 1974 and the presidency in 1976.

Watergate was an oligarchic hiccup, given that the most plausible reason for the Nixon White House–directed break-in at the Democratic National Committee was to retrieve evidence Nixon believed (wrongly) to be there of a $100,000 cash bribe (or perhaps $50,000) that he’d accepted from the billionaire Howard Hughes. When Hughes gave the bribe, he was worried that the Justice Department’s antitrust division wouldn’t let him buy the Dunes Hotel in Las Vegas, and also that the Atomic Energy Commission permitted nuclear testing in Nevada. “Howard Hughes wanted to own the president,” former Hughes deputy Robert Maheu explained in a 1973 deposition after Hughes fired him, “choose his successor, members of the Supreme Court, senators, congressmen, and politicians at all levels.”

Another oligarchical aspect of Watergate was its financing by slush funds solicited from corporations (illegally) and the rich, collected on occasion by Nixon’s oligarch best friend and factotum, the Florida multimillionaire Bebe Rebozo. Among Nixon’s most generous campaign donors was the oligarch W. Clement Stone (net worth: $500 million), a deeply eccentric self-made insurance tycoon who wore spats and began each day saying, “I feel happy! I feel healthy! I feel ter-r-r-ific!” Stone contributed nearly $5 million to Nixon’s presidential campaigns in 1968 and 1972 and later said he would have given $10 million if asked.

Stone preached a self-help gospel that he called PMA (for “positive mental attitude”) and claimed to have schooled Nixon in its precepts after his twin political defeats in the 1960 presidential election and the 1962 California gubernatorial election (the latter was where Nixon famously told the press, “you don’t have Nixon to kick around anymore”). “I found this terrific change in this man,” Stone told an interviewer in 1973, “this drastic change, almost 180-degree turn from somewhat of a negative personality to a positive personality.” Stone also insisted sunnily that “not a dime” of his money funded any of the unethical activities exposed in the various Watergate scandals, which seems improbable but was never disproved.

Ronald Reagan’s closest friends were a group of deeply conservative West Coast businessmen, known collectively as the kitchen cabinet, who’d gotten wealthy during the postwar boom in Los Angeles. The billionaire in this crowd was Walter Annenberg (net worth at death: $8 billion), whose annual New Year’s Eve dinner at his Rancho Mirage estate, Sunnylands, Reagan attended regularly. As president, Reagan named Annenberg’s wife, Leonore, White House chief of protocol. (Annenberg had previously been ambassador to London during the Nixon and Ford administrations.)

Reagan’s wife, Nancy, absorbed most of the criticism for the couple’s taste for lavish living, with critics comparing her to Marie Antoinette. The former Hollywood actress punctured this image in 1982 by making fun of it at the annual Gridiron Club dinner, singing to the tune of “Second Hand Rose” that she gave her secondhand clothes “to museum collections and traveling shows.” But as the Reagans prepared to leave Washington six years later, Time reported that she’d received gifts of designer dresses worth tens of thousands of dollars, ostensibly borrowed, and not reported them on the couple’s tax returns, prompting the first lady to claim they had been returned.

In retrospect, Nancy’s hazing was a bit sexist, because Ronald Reagan loved the rich no less than his wife did, and the ramifications were considerably more profound. Some trimming back of taxes and regulations had already occurred under President Jimmy Carter, but Reagan greatly accelerated these, dropping, for instance, the top marginal income tax rate from 70 percent to 28 percent. Reagan’s Democratic successors would ameliorate these changes somewhat, but mostly they couldn’t stop the pendulum from swinging rightward (the top rate has never again reached 40 percent). Even President Biden, who moved economic policy the furthest leftward of any of them, never made much headway on taxes. By 2018, Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman reported in their 2019 book, The Triumph of Injustice, effective tax rates on capital fell below effective tax rates on labor for the first time in at least 100 years. The proximate cause was Trump’s 2017 tax cut. Meanwhile, labor’s share of national income (relative to capital) fell from 67 percent in 2000 to 60 percent in 2024—its lowest level, the George Mason University economist Tyler Cowen calculated, since 1929. Human beings were losing ground to the almighty dollar.

Billionaires benefited the most. Last year, Zucman reported that although income taxes are progressive up to incomes of about $21 million, they reverse course and turn regressive after that, leaving billionaires with an effective tax of 8 percent. That’s less than half the effective tax paid by the “merely” rich. One reason was a growing reluctance to tax estates. The top marginal rate on estates dropped from 77 percent under Roosevelt and his successors to 70 percent under Carter to 55 percent under Reagan. President George W. Bush phased out the estate tax entirely in the early aughts, thereby enlarging the estates of billionaires John Kluge, Walter Shorenstein, and George Steinbrenner. President Obama revived the estate tax but didn’t dare raise the top threshold beyond 40 percent, where it remains today.

For the superrich, the Reagan Reversal didn’t happen solely at the federal level. States also started competing to eliminate the “rule against perpetuities,” which limited how many generations you could shield capital from taxation in a family trust. Before the 1980s, most states enforced the rule against perpetuities. But a wave of deregulation initiated by Congress in 1986 spread to the states, and today most states have repealed it. Even before Trump, it was the best time in at least a century to be a billionaire.

IX.

Trumpigarchy

Donald Trump has a troubled history with the Forbes 400. He first appeared in the 1982 tally with a net worth of $100 million, according to a 2018 Washington Post essay by former Forbes reporter Jonathan Greenberg. Trump tried and failed to persuade Greenberg that his family’s real estate business was worth more than $900 million. He even got his lawyer, Roy Cohn, to pester Greenberg. But Forbes went with $100 million. Trump and Cohn performed this Mutt and Jeff routine again in 1983, with Cohn now trying to persuade Greenberg that Trump was worth $700 million. Against his better judgment, Greenberg wrote that Trump had $200 million. In 1984, Greenberg bumped Donald up to $400 million after receiving a phone call from a fictitious “Mr. Barron” who was really and quite obviously Trump. “Mr. Barron” claimed Donald owned 90 percent of the family business, but Greenberg later found out that during that period Trump “had zero equity in his father’s company,” and that he should never have appeared on the Forbes list at all.

Trump eventually became a real billionaire, but he fell off the Forbes 400 list from 1990–1995 and in 2021 and 2023—these last two times partly because there were by now so many billionaires in America that the Forbes 400 list couldn’t include them all.

Trump’s travails with the Forbes 400 (and with money generally) reflect two traits—prevarication and instability—that are also the hallmarks of his presidencies. He’s an oligarch, but a shaky one, with a $500 million fraud judgment hanging over his head (the case is still on appeal in New York) and more than half his net worth (now $5.2 billion, per Forbes) tied up in social media and crypto stakes (which he didn’t pay for) that monetize his presidency and blatantly violate the emoluments clauses of the Constitution. If Aristotle saw aristocracy degrading into oligarchy, Trump is oligarchy degrading into kleptocracy.

In his first term, Trump passed—with lobbying assistance from Fred Smith, the oligarch president of FedEx (net worth: $5 billion)—a tax cut that, according to the nonprofit Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, will this year deliver an average of more than $60,000 to the one percent and less than $500 to the bottom 60 percent. Trump also lowered the top corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent. He now wants to lower it to 15 percent and to extend the first-term cut another 10 years.

Trump also harbors fantasies of displacing much of the progressive income tax with revenue raised from tariffs that, at least for now, he can impose without consulting Congress. “Instead of taxing our citizens to enrich other countries,” Trump said in his inaugural address, “we will tariff and tax foreign countries to enrich our citizens.” Trump’s commitment to this fever dream explains why he keeps slapping tariffs everywhere, taking them off when they send the stock and/or bond markets into a tailspin, then later reimposing them. He really wants that revenue! Trump’s billionaire oligarch Commerce Secretary Lutnick is reportedly working to set up something called the External Revenue Service to collect the duties.

You would think that if a government of, by, and for billionaires could do nothing else, it could keep the stock and bond markets from tanking. After all, nobody has more to lose from a plunging market than a billionaire. But a gift for making money does not translate into a gift for understanding economic policy. If it did, Andrew Mellon would have reacted less foolishly to the 1929 crash.

More charitably, Trump’s billionaires had every reason to conclude, from Trump’s first term, that when the interests of the MAGA rabble conflicted with those of the oligarchs, Trump would choose the oligarchs. Save for a few tariffs (which helped some workers and hurt others), and a somewhat tougher trade agreement with Mexico and Canada, endorsed by the AFL-CIO, that Trump no longer honors, the working class got bupkes out of Trump’s first term. Trump appointed anti-union members to the National Labor Relations Board, which governs labor-management conflicts; he reduced the number of workplace safety inspectors at the Occupational Safety and Health Administration; he dismantled fiduciary protections for retirement funds established by Obama; he allowed poultry plants with records of severe injuries such as amputations to increase line speeds; he threatened to veto any legislation that raised the minimum wage to $15; and he tried to repeal the Affordable Care Act.

The billionaires were correct to presume Trump would continue to screw the working class in his second term and, because of his anti-immigration stance, pay no political price for it. Theoretically, Trump’s crackdown on immigration threatened oligarchs by eliminating cheap labor, but it never achieved sufficient scale to cause them economic harm, and likely never will. They were also correct to presume that Trump would once again throw a wrench into the regulatory machinery (this time through mass firings, often illegal) and extend and expand the 2017 tax law’s giveaways to the rich. These are so pricey (along with proposed tax exemptions for overtime pay and tips that may never come to pass) that congressional Republicans briefly floated a tax hike on the wealthy. But Trump shot that down, first by suggesting he’d pay a price in the next election (never mind that Trump is barred by the Constitution from running again) and then by saying “a lot of the millionaires would leave the country.” The real reason he couldn’t support this was that it would bleed the oligarchs.

So yes, the billionaires were mostly correct in believing Trump would pamper them. Where they went wrong was in presuming Trump would not destroy the economy. He didn’t during his first term, but there’s a decent chance he will in his second, and the billionaires in his Cabinet (and his half-billionaire Treasury Secretary Bessent) may be powerless to stop him. At least one of those billionaires, Commerce’s Lutnick, spends half his time publicly egging Trump on to keep tariffs high (while privately saying he shouldn’t). The fact that Democrats always manage the economy better than Republicans, by any metric you can name, and have done so for the better part of a century, has never penetrated the billionaire oligarch’s skull, because that would require him to recognize that a.) lowering taxes does very little to stimulate economic growth and (as the bond market will tell you) quite a bit to undermine it; and b.) reducing regulation, especially in the financial realm, is profoundly destabilizing, as witnessed in the savings and loan crisis of the late 1980s and the subprime mortgage crisis of two decades ago.

Neither truth is anything a billionaire oligarch wishes to believe. This is compounded by the fact that the more money you possess, the less likely it is that anybody will ever want to tell you that you’re wrong about anything.

Add all this up and it’s difficult to know who in the Trumpigarchy is servant and who is master. On the one hand, Trump’s political fortunes and personal solvency depend on the goodwill of billionaires. Shortly after the inauguration, the blockchain analysis firm Chainalysis reported that 94 percent of the $TRUMP and $MELANIA memecoins (satire is dead) were owned by a mere 40 crypto “whales” in amounts worth $10 million or more. Their value subsequently fell steeply, prompting Trump to offer the top 220 memecoin holders an “intimate private dinner” with the president where they could “Hear close up, from President Trump, about the future of Crypto!” Everything is for sale.

On the other hand, the crazy Liberation Day tariffs and Trump’s idle threat to renege on some of the $36 trillion national debt, which was so potentially catastrophic that many news outlets pretended he didn’t say it, are a mentally unstable old man’s way of saying nobody, not even a billionaire oligarch, will tell him what to do. Nixon cultivated a “madman theory” to win concessions by frightening North Vietnam and the Soviet Union into believing he might otherwise vaporize them with nuclear bombs. With Nixon, it was an act. With Trump, it isn’t. He’s genuinely unwell, and though he doesn’t seem keen on dropping nuclear bombs, he does like to flirt with creating a global depression. In which case it might finally dawn on billionaires that they chose the wrong horse. Until then, the balance of power between Trump and his billionaires will shift back and forth.

X.

The Road From Here

Aristotle, who was no great fan of democracy, nonetheless concluded that it

appears to be safer and less liable to revolution than oligarchy. For in oligarchies there is the double danger of the oligarchs falling out among themselves and also with the people…. We may further remark that a government which is composed of the middle class more nearly approximates to democracy than to oligarchy, and is the safest of the imperfect forms of government.

Amen. But Aristotle offered no guidance on what to do about an oligarchy that acquires power by democratic means. Nor did he reckon that the middle class would dwindle—from 61 percent in 1971, according to a Pew Research Center study, to 51 percent in 2023.

In 1976, J. Paul Getty died the world’s richest man, with $6 billion. Elon Musk has $431 billion. Correcting for inflation, he’s more than 10 times wealthier than the richest man in the world half a century ago.

Aristotle could not possibly conceive the proliferation and growing wealth of the American billionaire. In 1976, Getty died the world’s richest man, with $6 billion. Musk has $431 billion. Correcting for inflation, the richest man in the world today is more than 10 times wealthier than the richest man in the world half a century ago. Jeff Bezos and Mark Zuckerberg are each six times wealthier than Getty was. Larry Ellison and Warren Buffett are five times wealthier. Even the Walmart heiress Alice Walton is three times wealthier than Getty, and that’s after she spent hundreds of millions to build Crystal Bridges, a world-class art museum in Bentonville, Arkansas.

When you possess this much money, buying political influence looks like a bargain. Warren Stephens spent a combined $7 million to purchase his ambassadorship. But that’s nothing compared to the $31 million he paid a decade ago to buy a mansion in Carmel, California. Jeff Bezos spent $250 million to buy The Washington Post a dozen years ago. But he paid twice that to purchase the world’s largest sailing yacht, which clocks in at 417 feet and plies the seven seas with a support vessel that’s 246 feet long and carries additional crew.

The oligarch Donald Trump, in auctioning himself and American government to the highest bidder, may well match or surpass the stew of corruption that Washington created during the Gilded Age. That’s on him. But it’s on the rest of us that over 50 years, through economic policies that coddled the rich under both Democrats and Republicans, American wealth concentrated to such a degree that a Trump presidency—make that two Trump presidencies—was not only possible, but perhaps inevitable.

We have the power to stop, through more sensible tax and regulatory policies and a resurgence of union organizing, the torrent of wealth flowing upward to billionaires. I worry a lot about what will happen if we don’t act soon. Many people fear an abrupt end to democracy under Trump. I don’t, especially. What I do fear, though, is that unless we find a way to correct the wealth-based power imbalance that gave us Trump in the first place, our democracy will flicker out more gradually. To paraphrase Louis Brandeis: We can keep our democracy, or we can hatch our first trillionaire. We really can’t do both.

All figures in this piece are accurate as of May 28, 2025. The values shown are subject to market fluctuations.

The post How the Billionaires Took Over appeared first on New Republic.