Decades ago, Pete Wilson did something unusual. The U.S. senator came home to run for California governor.

The path to power typically goes the opposite direction, with governors trading the statehouse for the (perceived) influence and prestige of being one of just 100 members of a club that fancies itself — not so humbly or precisely — as “the world’s greatest deliberative body.”

Wilson bucked that sentiment.

“It is a much more difficult role,” he said of being governor, and one he came to much prefer over his position on Capitol Hill.

It turns out that Wilson, a Republican who narrowly prevailed in a fierce 1990 contest against Democrat Dianne Feinstein, was onto something.

Since, then five other lawmakers have left the Senate to become their state’s governor. Several more tried and failed.

Although it’s still more common for a governor to run for Senate than vice versa, in 2026 as many as three sitting U.S. senators may run for governor, the most in at least 90 years, according to the nonpartisan Cook Political Report.

Clearly, the U.S. Senate has lost some of its luster.

There have always been those who found the place, with its pretentious airs, dilatory pacing and stultifying rules of order, a frustrating environment to work in, much less thrive.

The late Wendell Ford, who served a term as Kentucky governor before spending the next 24 years in the Senate, used to say “the unhappiest members of the Senate were the former governors,” recalled Charlie Cook, founder of the eponymous political newsletter. “They were used to getting things done.”

And that, as Cook noted, “was when the Senate did a lot more than it does now.”

What’s more, the Senate used to be a more dignified, less partisan place — especially when compared with the fractious House. An apocryphal story has George Washington breakfasting with Thomas Jefferson and referring to the Senate as a saucer intended to cool the passions of the intemperate lower chamber. (It helps to picture a teacup filled with scalding brew.)

These days, both chambers are bubbling cauldrons of animosity and partisan backbiting.

Worse, there’s not a whole lot of advising going in the Senate, which reflexively consents to pretty much whatever it is that President Trump asks of the prostrated Republican majority.

“The Senate has become an employment agency where we just have vote after vote after vote to confirm nominees that are are going to pass, generally, 53 to 47, with very rare exceptions,” said Colorado Sen. Michael Bennet, a Democrat who’s running to be governor of his home state.

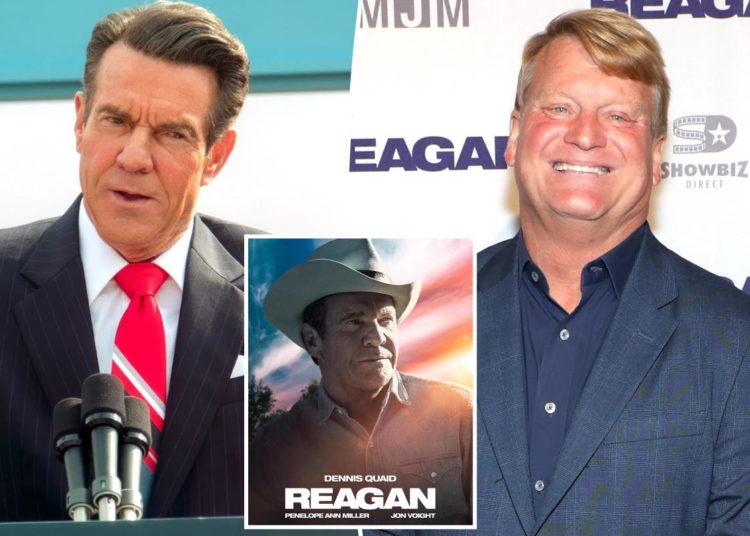

The other announced gubernatorial hopeful is Alabama Sen. Tommy Tuberville, a Republican who’s made no secret of his distaste for Washington after a single term. Tennessee’s Marsha Blackburn, a fellow Republican fresh off reelection, is also expected to run for governor in her state.

Bennet arrived in the Senate 16 years ago and since then, he said, it’s been “really a one-way ratchet down.”

“You think about the fact that we’re really down to a couple [of] bills a year,” he said this week between votes on Capitol Hill. “One is a continuing resolution that isn’t even a real appropriations bill … it’s just cementing the budget decisions that were made last year, and then the defense bill.”

Despite all that, Bennet said he’s not running for governor “because I’m worn out. It’s not because I’m frustrated or bored or irritated or aggravated” with life in the Senate, “though the Senate can be a very aggravating place to work.” Rather, working beneath the golden dome in Denver would offer a better opportunity “to push back and to fight Trumpism,” he said, by offering voters a practical and affirmative Democratic alternative.

Try that as one of 47 straitjacketed senators.

When Wilson took office in January 1991, he succeeded the term-limited George Deukmejian, a fellow Republican.

He immediately faced a massive budget deficit, which he closed through a package of tax hikes and spending cuts facilitated by his negotiating partner, Democratic Assembly Speaker Willie Brown. Their agreement managed to antagonize Democrats and Republicans alike.

Wilson didn’t much care.

After serving in the Legislature, as San Diego mayor and a U.S. senator, he often said being California governor was the best job he ever had. There are legislators to wrangle, agencies to oversee, natural disasters to address, interest groups to fend off — all while trying to stay in the good graces of millions of often cranky, impatient voters.

“Not everybody enjoys it,” Wilson said when asked about the prospect of Kamala Harris serving as governor, “and not everyone is good at it.”

Harris, who served four years in the Senate before ascending to the vice presidency, has given herself the summer to decide whether to run for governor, try again for the White House or retire from politics altogether.

California’s next governor will probably have to take some “very painful steps,” Wilson said, given the dicey economic outlook and the likelihood of federal budget cuts and other hostile moves by the Trump administration. That will make a lot of people unhappy, including many of Harris’ fellow Democrats.

How would she feel about returning to Sacramento’s small stage, wrestling with intractable issues such as the budget and homelessness, and dealing with the inevitable political heat? We won’t know until and unless Harris runs.

The post Barabak: As the Senate loses luster, more members run for governor. Is there a takeaway for Kamala Harris? appeared first on Los Angeles Times.