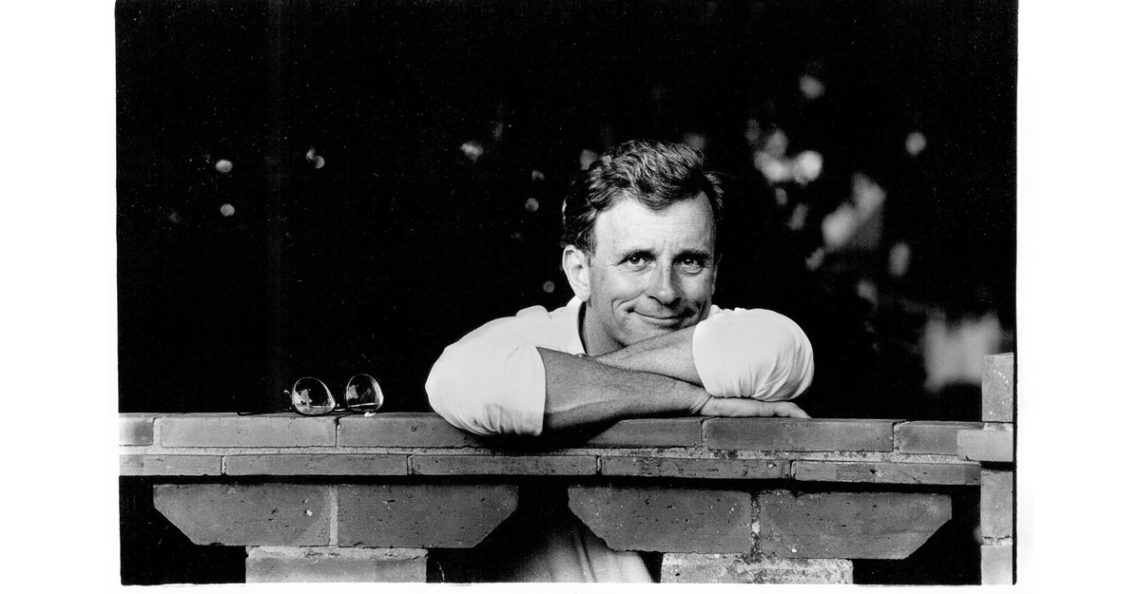

Edmund White had the most beautiful blush. I recall watching him at a celebration of his work while one of his most sexually explicit essays (which is saying a lot) was read aloud—my mind had to perform its own gymnastics just to picture all the right organs in the right receptacles. Ed’s blush somehow managed to overlap his cheeks and spread across his chin, his forehead, his ears, and into his greatest receptacle of all: his kindly, contemplative soul.

No one blushed like Ed. And when you saw him blush, you saw a midwestern child still agog at the wide world and the fact that it would accept him. The path between his homeland of Cincinnati and the salons of New York and Europe seemed smoother than it had been, just like the ease and unaffected nature of Ed’s prose hid the great artistry behind it. You could find Ed dining with Italian baronessas or at some unspectacular joint in Key West or within the wonderfully messy and book-strewn confines of his own apartment, and there would always be the same blush across his face.

He giggled a lot. This may seem like an unimportant fact when talking about one of America’s greatest writers, but Ed’s giggle came from the same place as his blush. He giggled as if you were tickling him, like a naughty child perpetually discovering his naughtiness. Maybe that was the secret to Ed. The co-author of The Joy of Gay Sex was never jaded; he never let go of pleasure, even as age and illness conspired to take it away. He recently published one of his best books, The Loves of My Life, which, yes, is another Ed White memoir but is also a brilliant argument for the importance of sex and love, in all their conjoined variations, to the human animal and, by extension, to the artistic work we animals produce. In the age when the messy mechanics of sex have been asked to depart the page for the world of fetishized porn, Ed demanded that literature retain the ecstasy and desperation and glorious ridiculousness of two (or sometimes many more) bodies thumping against each other. He loved sex the way some of his younger contemporaries love recognition or a well-cooked egg at brunch.

And the joy of love and sex and the joys of talking and writing were all intertwined in Ed’s mind and work. I appreciate gossip myself, but Ed turned gossip into an art form. To hear him gossip was music. He was breathless, engaged, in love with the tale he was telling. And because of the mastery with which he was able to process the endless social parade in front of him, his gossip was a form of prepublishing. People, myself included, told Ed everything, both because we loved him and ached to see him giggle and because we wanted him to be a naughty interpreter of our lives.

It is customary in an appreciation of this sort to mention when one met the recently departed, but I honestly can’t remember. I would guess it was 23 years ago, because as soon as you published your first book, there was Ed in all his blushing, giggling glory. And often next to Ed, holding a single malt, there would be an unsmiling writer of great pretension looking down at you from a great height. I knew immediately which kind of writer I wanted to be.

I remember one drunken night walking through the inner rooms of his apartment as an outrageous party unfolded in the main quarters, taking photos (with an early phone that was barely up to the task) of his bedroom and bathroom, all of it unremarkable and slathered in normalcy, and thinking, This is what a great writer’s home should look like. The lessons of his life and work are there on every page of his books, a portable MFA for the taking. Keep your eyes open, record everything, fall in love constantly, radiate kindness whenever you can, even when you have to dig deep through the morass of history, biography, and bigotry to find it. Many of my best writer friends have passed away in their 50s; Ed lived a full life by every measure, and still his passing is a unique form of loss. No one out there has even a tenth of his blush.

The post The Naughty Interpreter of Our Lives appeared first on The Atlantic.