As soon as one presidential election ends, the next one begins.

Potential Democratic nominees are starting to make some noise. California Gov. Gavin Newsom has been hosting a podcast in which he engages conservative voices to demonstrate his centrist bona fides. Maryland Gov. Wes Moore has been making the rounds, giving speeches and vetoing legislation establishing a reparations commission. Former Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg keeps giving lectures and interviews targeting independents and red America. Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro is talking about “getting shit done” while Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Sen. Bernie Sanders have been drawing huge crowds in their rallies against oligarchy. Former Vice President Kamala Harris has not decided what she will do. Many other prospects are waiting for the right moment to enter the fray.

The challenge that they all face is formidable. Democrats will have to contend with the deep unpopularity of their party in the aftermath of Joe Biden’s presidency. According to the polls, congressional Democrats are not trusted or liked. Another major survey found that, despite the tumult of tariff policies, as late as April, more Americans trusted President Donald Trump to do a better job with the economy than Democrats. Democrats, voters say, are more out of touch with the electorate than Republicans. The new spate of books about the 2024 campaign fuels distrust about Democrats that stems from perceptions that the party leaders were dishonest about Biden’s mental condition.

Finding the best candidate will not be easy. Some of the search will revolve around the personality and charisma of the individuals interested in the job. Who does best in the contemporary media ecosystem? Which candidate draws the most energy and crowds at rallies?

Yet to win the general election, the criteria must be much broader. Democrats need a true coalition builder, a politician with the strategic savvy to break through the calcified electoral map by putting together a campaign to bring out loyal voters and win back the battleground states that went red in 2024.

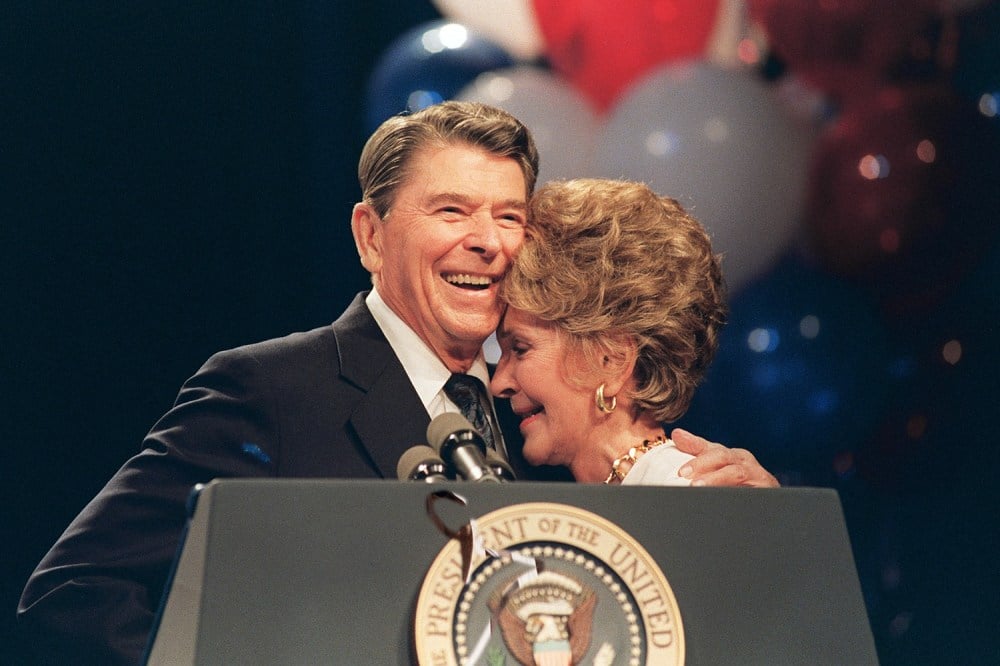

For a candidate who met such a challenge, Democrats should look to their opponents’ history. Though antithetical to the principles they represent, Ronald Reagan’s path to the presidency in 1980 offers an instructive roadmap about what needs to be done in the next few years.

When Reagan, a former Hollywood actor, California governor, and conservative spokesperson, decided to run for the presidency, the United States was in terrible shape. The economy was reeling from stagflation—the double punch of high inflation and unemployment that Keynesian economists had previously insisted was impossible—and an ongoing energy crisis that kept Americans waiting in long lines for gas and paying higher prices to heat their homes. Deep divisions existed over issues such as race and gender relations, cultural values, and the role of the free market.

Public distrust in government, fueled by Vietnam and Watergate, kept worsening over the decade. There was minimal confidence in the capacity or legitimacy of U.S. foreign policy. By the time the fall campaign got underway, the Soviet Union had invaded Afghanistan—shattering any hope that the policy of détente, which sought to ease relations with the Soviet Union, could continue. American hostages were being held captive by revolutionaries in Iran.

Elected in 1976, Democratic President Jimmy Carter had become deeply unpopular. His approval rating had fallen to 39 percent by the end of March. Perceived by many voters to be an ineffective leader, Republicans warned that it would have catastrophic effects if Carter were given four more years. Meanwhile, Massachusetts Sen. Ted Kennedy mounted a serious primary that rallied Democrats who believed Carter had moved their party in the wrong direction.

In 1976, when Reagan had challenged Republican President Gerald Ford in the primaries and nearly won, a majority of the punditry still suspected the former California governor was too radical to win national office. They were wrong. In November 1980, Reagan won the highest office and kicked off a two-term presidency that transformed national politics by shifting the country to the right. Besides being highly effective in front of the television cameras, how did he pull it off? How did Reagan save the GOP from the wreckage of Watergate? How did he put together a conservative coalition that would outlast his time in office and which continues to shape national politics?

Perhaps most importantly, Reagan connected himself to the burgeoning grassroots conservative movement that generated the energy behind Republican politics by the end of the 1970s. Rather than centering himself within Washington and defining himself as part of the establishment, Reagan embraced the forces from below that were reshaping national debates. Reagan allied himself with the evangelical Christians who had mobilized as the Moral Majority by championing conservative cultural values such as limitations on abortion. He opened his doors to disaffected Democrats, from neoconservatives who were no longer comfortable with their party’s perceived pullback from a muscular national security program to a growing number of ethnic urban voters frustrated with the direction of social policy starting in the 1960s under former President Lyndon B. Johnson. One of the most iconic moments in the campaign occurred when Reagan appeared before the National Affairs Briefing Conference in Dallas, representing ministers that officially could not support either candidate. “I know this is a nonpartisan gathering, and so I know that you can’t endorse me, but I only brought that up because I want you to know that I endorse you and what you’re doing.”

To bring these groups into the fold without losing the support of existing factions in the GOP, such as big business, finance, and traditional Midwestern Republicans, Reagan effectively zeroed in on three broad themes that were capable of solidifying rather than fracturing his coalition: anti-communism, reducing the size of government, and lowering taxation.

Though Reagan touched on many specific issues throughout the 1980 campaign, he was disciplined in terms of bringing back the debate to issues that didn’t factor into his emerging support. He attacked Democrats for cutting funding on national security. He insisted that the policy of détente—born of Richard Nixon’s presidency—would never work since the Soviets could not be trusted. He repeatedly made the argument that private markets worked better than federal regulation (famously captured in his inaugural speech, when Reagan told the nation that “government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem”). The only pathway out of the economic malaise, Reagan said, was less government. Building on the tax revolt that rocked California in 1978, culminating in Proposition 13, which capped property taxes, he championed steep reductions in the overall tax rates. “High taxes,” he noted in his acceptance speech at the convention, “we are told, are somehow good for us, as if, when government spends our money, it isn’t inflationary, but when we spend it, it is.”

As he entered national politics, Reagan distanced himself from problematic members of his own party. Though wary of making critical comments about Watergate in particular, Reagan made it clear that he was not part of the old system. During his run for the nomination in 1976, Reagan focused much of his firepower on détente, which Ford had continued after Nixon. Using Secretary of State Henry Kissinger as his foil, Reagan insisted that his own party had entered into dangerous negotiations with the Soviet Union. Unlike his opponents, such as former Republican National Committee Chairman George H. W. Bush, Reagan stood outside the broken party establishment, not within it.

And in 1980, Reagan never let voters take their eye off Carter. Many of Reagan’s speeches and campaign ads promised voters he would defeat Carter and the broken policies that his administration represented. In one address that took place in front of the Statue of Liberty, Reagan famously declared: “A recession is when your neighbor loses his job. A depression is when you lose yours. Recovery is when Jimmy Carter loses his.” Although Wall Street financiers didn’t have much in common with Southern evangelical Christian voters, they could easily unite around their hatred of Carter and Democratic politics.

Reagan defeated Carter with a massive Electoral College victory, 489 to 49 electoral votes. Carter was only victorious in six states and the District of Columbia. Independent candidate John Anderson, a former Illinois Republican who had run championing the center, obtained about 7 percent of the popular vote. By contrast, the right-wing Reagan secured over 50 percent of the popular vote. Republicans also won control of the Senate for the first time since 1954 (Democrats maintained control over the House).

The results were a decisive and formidable victory for Reagan and American conservatism. Notably, Reagan broke through traditionally Democratic territory by winning most Southern states. Other than with Hispanic and Black voters, Reagan shrank Carter’s advantage with several core Democratic constituencies, including American Jewish voters and union families.

Reagan succeeded not by moving to the center but by moving his party to the right. He had taken ideas once perceived to be too radical in mainstream electoral politics and sold them to a majority of the nation. He had connected his candidacy and party to a mass grassroots movement and, in doing so, won the presidency.

In 2025, Democrats can learn a great deal from Reagan’s run.

The successful Democratic candidate must be a person who can energize the grassroots progressive and liberal groups that constitute the party’s heart and soul. While the successful candidate will not be able to please everyone, and there will be fault lines to overcome, the next Democratic nominee must harness rather than run away from the kind of organizations that delivered the vote for Barack Obama in 2008 or Democratic candidates in the 2018 midterms.

A successful candidate will also need to figure out what issues to prioritize that will serve as bridges between the factions, rather than zeroing in on contentious issues that exacerbate wedges.

Like Reagan in 1980, the Democratic nominee can’t be scared to break with their own party establishment, which right now is deeply unpopular with the country. Democratic voters and independents must be able to see that they would offer something different and fresh.

Finally, regardless of whether Trump attempts to circumvent the 22nd Amendment and run for a third term, the candidate will need to keep voters focused on the threat that MAGA Republicanism poses to education, the social safety net, the economy, foreign policy, and the nation’s cherished constitutional fabric.

To be sure, the Democratic nominee will face challenges that simply did not exist in 1980. For example, the current media is more fractured and polarized. The Republican Party is far more radical, willing to do whatever is necessary to protect power. Political preferences have also hardened in the age of polarization, making it far more challenging to shift any voter preferences.

But this is what it will take. As the Democrats start sorting through this decision, the party would do well to keep a clear set of criteria in mind, avoiding an exclusive focus on personality and viral moments, to keep focused on who can forge a coalition that can land Democrats in the White House by January 2029.

The post What Ronald Reagan Can Teach Democrats in 2025 appeared first on Foreign Policy.