They took to the streets en masse through last winter, braving icy weather, sitting on freezing pavements through snowy nights to call for the ouster of then-South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol. Politicians praised them as “the hope for the whole nation” who “saved our democracy.”

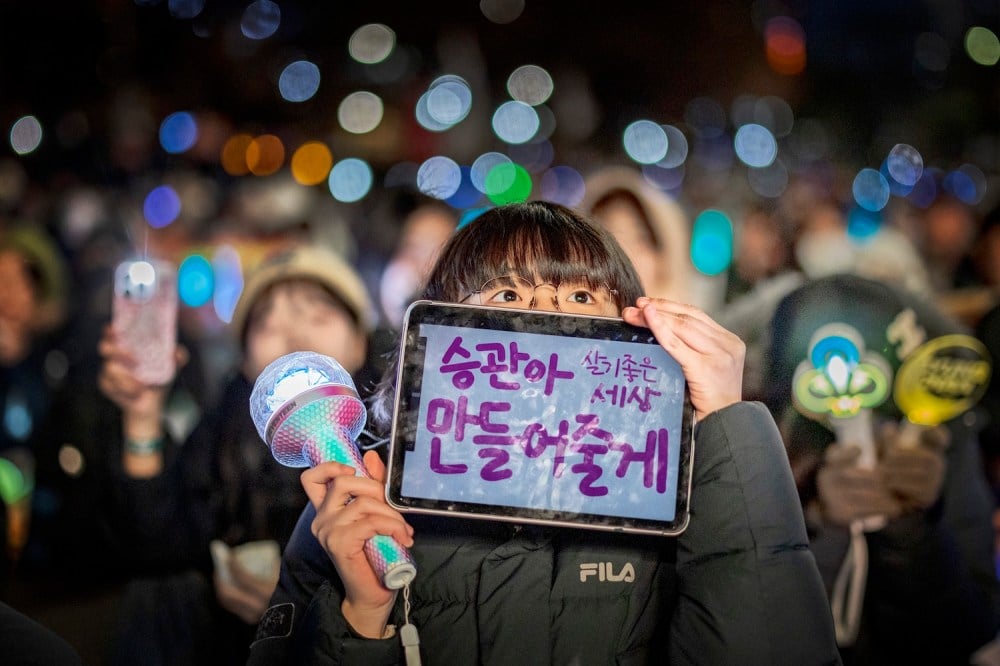

Young women were a major force behind the months-long protests that helped bring down Yoon in April after his unconstitutional declaration of martial law last December. Waving bright K-pop light sticks that turned the streets into a sea of colorful lights, their presence was so overwhelming that the anti-Yoon protesters became known as the “light stick troops” and their movement the “light stick revolution.”

Yoon had risen to power on an anti-feminist platform in 2022, riding a wave of misogynistic sentiment among young men in South Korea—no surprise, then, that young women were highly motivated to remove him from power. But while Yoon’s brief, shock imposition of martial law triggered an ongoing political crisis, it also put the spotlight on one of South Korea’s biggest political failures. Despite the prominent role played by women in pro-democracy demonstrations, both past and present, there are barely any women in positions of political power.

This is no accident but the result of deep, structural inequities. South Korea is the world’s 12th-largest economy as well as a tech and pop culture powerhouse—it also has one of the worst records on women in the industrialized world. The country has the largest gender pay gap among members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), with women earning under 70 percent of what men earn. Women make up only 6 percent of corporate boardrooms.

The political sphere is no different—women account for 20 percent of parliamentary seats, only slightly higher than the share in North Korea and well below the OECD average of 34 percent. When South Koreans hit the ballot box in Tuesday’s presidential election to select their replacement for Yoon, all seven of their options will be men.

The recent outburst of female activism was driven by anger over Yoon’s martial law as well as his anti-feminist policies. But it also highlighted many young women’s desire to challenge the country’s deeply male-dominated politics. One popular political slogan summed up the sentiment: “The hands holding the K-pop light sticks will one day hold the [speaker’s] gavel.”

“Women and girls drove the momentum of many mass demonstrations during our key political moments,” said Jung Choun-Sook, a former two-term lawmaker with the center-left Democratic Party (DP). “But these women were often sidelined as cheerleaders with no real political power once the protests were over and the political dust settled. I really hope that things will be different this time.”

Twenty percent of parliamentary seats being held by women might seem low, and it is. But it is still a record for South Korea, the result of decades-long efforts by women such as Jung.

Unlike in many other countries where women fought for years to win suffrage, equal voting rights for women were included in South Korea’s first constitution, which was drafted after the end of Japanese colonial rule in 1945. Still, when the country’s first elections were held in 1948, not one of 198 elected officials was a woman.

It was only in a by-election held a year later that the country elected its first female parliamentarian, Im Yeong-sin. Im, a close friend of then-President Syngman Rhee, later also served as trade minister, facing down protests from some male officials that “those who urinate while standing can’t report to a person who urinates while seated.” This would set the tone for the years to follow.

Women remained a tiny minority in the National Assembly, comprising about 10 out of 300 seats all the way until the 1990s. It was only after the country introduced gender quotas in 2000—requiring political parties to nominate women for at least 30 percent of proportional candidate seats—that the number of female lawmakers started to increase meaningfully. Feminist groups pushed for the change, and a strong wave of feminist and #MeToo movements have further fueled calls for more political representation of women and paved the way for landmark laws to combat gender discrimination and violence.

In response to these shoots of progress, the women’s movement has faced a major backlash. The right-wing People Power Party (PPP)—of which Yoon was a member until he became president—began tapping into growing anti-feminist sentiment among young men to win elections. Under Yoon’s administration, budgets to help victims of gender violence and discrimination were slashed. The country’s gender equality ministry—which Yoon had threatened to dismantle—lost much of its influence. Women perceived to be feminists faced growing threats of discrimination, bullying, or physical attacks for reasons including simply having short hair.

Against this backdrop came Yoon’s martial law debacle—driving Arden Jung, a 31-year-old graphic designer, to spend every single weekend from December to April marching on the streets of Seoul.

“There was this boiling anger among women like me about all the attacks on women, whether misogynistic violence or AI-generated deep-fake porn crimes,” she said. “So, when the [anti-Yoon] protests began, I thought: ‘Now is the time to go out and speak my mind. We’ve really had enough—we can’t take this anymore.’”

She took part in nearly 30 demonstrations, waving a large flag emblazoned “Introvert” to encourage other introverts to come out and join her. The flag went viral, and she soon found herself surrounded by throngs of protesters who silently marched along with her.

Women ages 20 to 40—who comprise 12 percent of the total population—accounted for about a third of hundreds of thousands of protesters during the peak of the anti-Yoon rallies. Many women like Jung were already well prepared, having led or joined numerous women’s street protests in recent years—whether campaigning for abortion access or condemning widespread tech-based sexual abuse.

“In many [anti-Yoon] protests, the front rows were always occupied by young women waving K-pop light sticks,” said Park Hee-won, an organizer of the recent rallies. “I could even recognize some of them because they were always there on the front rows, day after day, week after week, rain or shine.”

For months, women took to the protest stage calling for the creation of an anti-discrimination law, more gender equality education at school, and reforming a restrictive law that defines rape on the basis of physical violence, not consent.

Yoon’s impeachment brought hope for the young women seeking these changes. But political polarization in the country—especially the widening “gender divide” among its youth—has complicated such prospects.

South Korean voters have often been split by region or generation, with older people supporting the PPP and those in their 40s and 50s, who came of age during the anti-military dictatorship movement of the 1980s, largely voting for the DP.

But voters under 40 are sharply divided by gender. Women tend to vote for the DP or more progressive parties, while men are supporting right-wing parties such as the PPP, according to several surveys and the election results of recent years.

Ironically, this has led to both of the main parties shunning women’s issues.

“The PPP thinks, ‘Young women won’t vote for us anyway,’ and the DP thinks, ‘They’ll vote for us anyway, so we need to work harder to woo young men,’” said Jung, the ex-lawmaker.

Since Yoon and the PPP weaponized anti-feminism, gender equality and feminism have become “controversial, burdensome issues few would want to touch” across the political aisle, Jung said. Many politicians and activists agree.

“It’s the presidential election season. But no gender policies or policies for gender equality are being announced anywhere,” Chung Choon-saeng, a lawmaker of the liberal minority Rebuilding Korea Party, said in early May. One news magazine called the upcoming election “the presidential election for the half [of the population].”

While women expect little from the PPP, there has been growing anger at the DP’s silence on the issue. Lee Jae-myung, the DP’s presidential candidate and front-runner in the race, positioned himself as a champion of women’s rights during his failed 2022 presidential bid against Yoon. This time around, he remained mum on the issue for months, only announcing policies to combat gender violence and workplace discrimination after weeks of public criticism and mounting calls by rights groups to “respond to the voices of women voters.”

“For us, it’s considered strategically unwise to describe certain policies as those for ‘women’ or ‘gender equality’ too much because as soon as we utter those words, it becomes a source of political controversy, leaving us vulnerable,” one senior DP aide said on the condition of anonymity. The party is instead taking a “low-key approach” by incorporating women’s issues in policies for youth, labor, or other fields “quietly” so as not to risk offending young male voters, the aide said.

But Jung warned that women’s issues are at the heart of many pressing problems faced by South Korean society.

South Korea has the world’s lowest birth rate, with women far less likely to want to marry or have children than men, posing a looming demographic disaster for the economy. Researchers point to the patriarchal family culture and the significant double burden on working moms, who are much more likely to experience career setbacks in male-dominated workplaces.

With fewer babies born each year, South Korea is also one of the world’s fastest-aging societies. It’s expected to lose more than half of its 51 million population by the end of the century. Half its population is expected to be above the age of 65 within 50 years—already, 40 percent of South Korea’s older people live below the poverty line, the highest among the advanced economies. Women make up 60 percent of the above-65 population and have a significantly higher rate of poverty than men in that age group.

“How are we going to tackle all these problems if the government and politicians don’t openly address gender inequality?” Jung said.

Things have reached the point that some young women look to avoid romantic relations with men all together, under the slogan of “4B,” or four “nos”—to childbirth, marriage, dating, and sex with men. Part of a social trend dubbed “birth strike” or “marriage strike,” Yoon and the PPP have capitalized on this phenomenon to stir up more anti-feminist sentiment.

Undeterred, more “no-marriage women” or “willfully unmarried women” are forming communities with like-minded peers to grow old together and care for one another, pointing to potential solutions for the challenges that lie ahead. They call for more policy support for one-person households or laws that extend rights and services available to conventional families to a broader range of companionships that includes those not related by blood or marriage.

Jung, the protester, says she feels stuck between a rock and a hard place. She is desperate to push the PPP out of power but also wary of being taken for granted by the DP, “like fish that have already been caught” and thus no longer need to be fed. But she remains optimistic, saying her experience of the solidarity formed in recent protests marked a “turning point” for many like her.

“Protests and political mobilization have been literally our daily life for the past four months,” she said. “I’m ready to hit the streets again if politicians keep refusing to listen to our voices. We’ll watch how—or whether—the politicians will respond to our voices with our eyes wide open, our fists clenched, and our light sticks and flags ready.”

The post South Korean Women Are Powerful—and Powerless appeared first on Foreign Policy.