This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

During Donald Trump’s first stint as president, the political scientist Daniel Drezner maintained a very long thread on the site formerly known as Twitter. Each entry had the same text—“I’ll believe that Trump is growing into the presidency when his staff stops talking about him like a toddler”—followed by the latest example.

Trump’s second term has been similar to his first, just ratcheted up a notch, and his childlike impatience is Exhibit A. The president has a very short attention span, gets frustrated when things don’t work quickly, and tends to demand fast changes in policy. When Russia’s Vladimir Putin is not willing to end the war in Ukraine in 24 hours, rebel groups aren’t quickly cowed by air strikes, or trade wars do not prove so easy to win, Trump gets bored and restless. Then he tries to shake things up with ill-tempered social-media posts, broadsides at policy makers, or premature declarations of victory.

During his first term, some of Trump’s advisers worked to moderate those impulses. That meant he got sick of them quickly and cycled through them, but it did slow the speed with which he changed positions. Now that there are fewer of the proverbial adults in the room—whoops, there’s that infantilizing language again—Trump’s impatience has become a central thread for understanding his administration.

In the case of the war in Ukraine, for instance, Trump’s unrealistic expectations led to him blowing up at President Volodymyr Zelensky in an Oval Office meeting. Earlier this month, he posted that he was “starting to doubt that Ukraine will make a deal with Putin,” who had suggested peace talks in Turkey. “Ukraine should agree to this, IMMEDIATELY,” Trump wrote, as though a yearslong conflict could and should be resolved so abruptly. Zelensky took understandable umbrage at the Oval Office ambush, but he seems to have realized that by adopting a more conciliatory tone, he can underscore Putin’s intransigence. Now, as my colleague Tom Nichols wrote yesterday, Trump is raging against Putin, who has been entirely focused on dragging out a war of attrition. That may sap Ukraine’s resources, but it also saps Trump’s patience.

A more patient president would pose less threat to the constitutional order. Some of Trump’s most notable collisions with the law and courts are less a product of him wanting powers that he doesn’t have than about him wanting things to happen faster than his powers allow. The president has a great deal of leeway to enforce immigration laws, but he is unwilling to wait while people exercise their right to due process, so instead he tries to just erase that right.

Trump could lay off many federal workers using the legally prescribed Reductions in Force procedure; instead, he and Elon Musk have attempted to fire workers abruptly, with the result that judges keep blocking the administration. Similarly, Trump could try to get Congress to close the Education Department or rescind funding for NPR, especially given the sway Trump holds over Republicans in both the House and the Senate. Instead, he has tried to do those things by executive fiat. Last week, a judge blocked his effort to shut down the department, and this week, NPR sued the administration over the attempt to slash funding, arguing that only Congress can claw back funds it has appropriated. (Politico reported today that the administration is finally planning to ask Congress to bless spending cuts made by Musk’s U.S. DOGE Service.)

As these examples show, impatience is also a threat to Trump’s own agenda. This is especially apparent in the case of trade. Although Trump has been a fan of protectionism since the 1980s and has been the president on and off since 2017, he still hasn’t taken the time to think through a plan for actually implementing tariffs.

Consider the baffling path of trade policy toward the European Union over the past week. On Friday, Trump abruptly declared that he would “recommend” 50 percent tariffs on the EU. “I’m not looking for a deal,” he said later that day. “We’ve set the deal—it’s at 50 percent.” On Sunday, he said that he was delaying the tariffs until July 9. He now says that both sides have agreed to trade talks. This kind of unpredictability certainly got attention from EU officials, but the strategy that brings them to the table is unlikely to make them very trusting of Trump’s good faith as a negotiator.

And why would they believe him? They’ve seen the pattern of his impatience. Trump has threatened, levied, suspended, and re-levied tariffs on Canada and Mexico, and threatened more tariffs on China. This vacillation has earned lots of headlines and induced lots of foreign officials to try to make nice with Washington, but it hasn’t produced much in the way of actual trade agreements. Earlier this month, the White House trumpeted a “historic trade win for the United States,” which actually amounted simply to the U.S. backing down from enormous tariffs on China, and China canceling its retaliatory measures.

Trump’s impatience makes him not only an unreliable negotiator; it makes him a weak one. When he spoke with U.K. Prime Minister Keir Starmer earlier this month, Trump was desperate to notch a win, having already claimed without any evidence to have struck 200 trade deals (more than the number of countries the U.S. recognizes in the world). The result was an extremely vague “preliminary” agreement that gave Britain relief from Trump’s tariffs without resolving many of the concrete trade questions between the two nations.

The White House dutifully boasted that this was a “historic trade deal.” The president may no longer have aides who speak about him in the press like he’s an exasperating child, but his approach hasn’t matured at all.

Related:

Here are three new stories from The Atlantic:

- David Frum: The Trump presidency’s world-historical heist

- How America lost control of the seas

- The administration takes a hatchet to the NSC.

Today’s News

- Elon Musk said that President Donald Trump’s tax bill would increase the federal deficit and that it “undermines the work” of his Department of Government Efficiency.

- Trump pardoned the reality-TV stars Todd and Julie Chrisley, who have served more than two years in prison for tax evasion and bank fraud.

- Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said that Mohammed Sinwar, Hamas’s Gaza chief, has been killed in an Israeli air strike.

Evening Read

How a Recession Might Tank American Romance

By Faith Hill

Even in this country’s darkest economic times, romance has offered a little light. In the 1930s, more jobs opened up for single women; with money of their own, more could move away from family, providing newfound freedom to date, Joanna Scutts, a historian and writer, told me. Nearly a century later, a 2009 New York Times article cited online-dating companies, matchmakers, and dating-event organizers reporting a spike in interest after the 2008 financial crash. One dating-site executive claimed a similar surge had happened in 2001, during a previous economic recession. “When you’re not sure what’s coming at you,” Pepper Schwartz, a University of Washington sociologist then working for PerfectMatch.com, told the Times, “love seems all the more important.”

Now, once again, people aren’t sure what’s coming at them.

More From The Atlantic

- A reality check for tech oligarchs

- Trump’s campaign to scare off foreign students

- The David Frum Show: J. D. Vance’s bargain with the devil

Culture Break

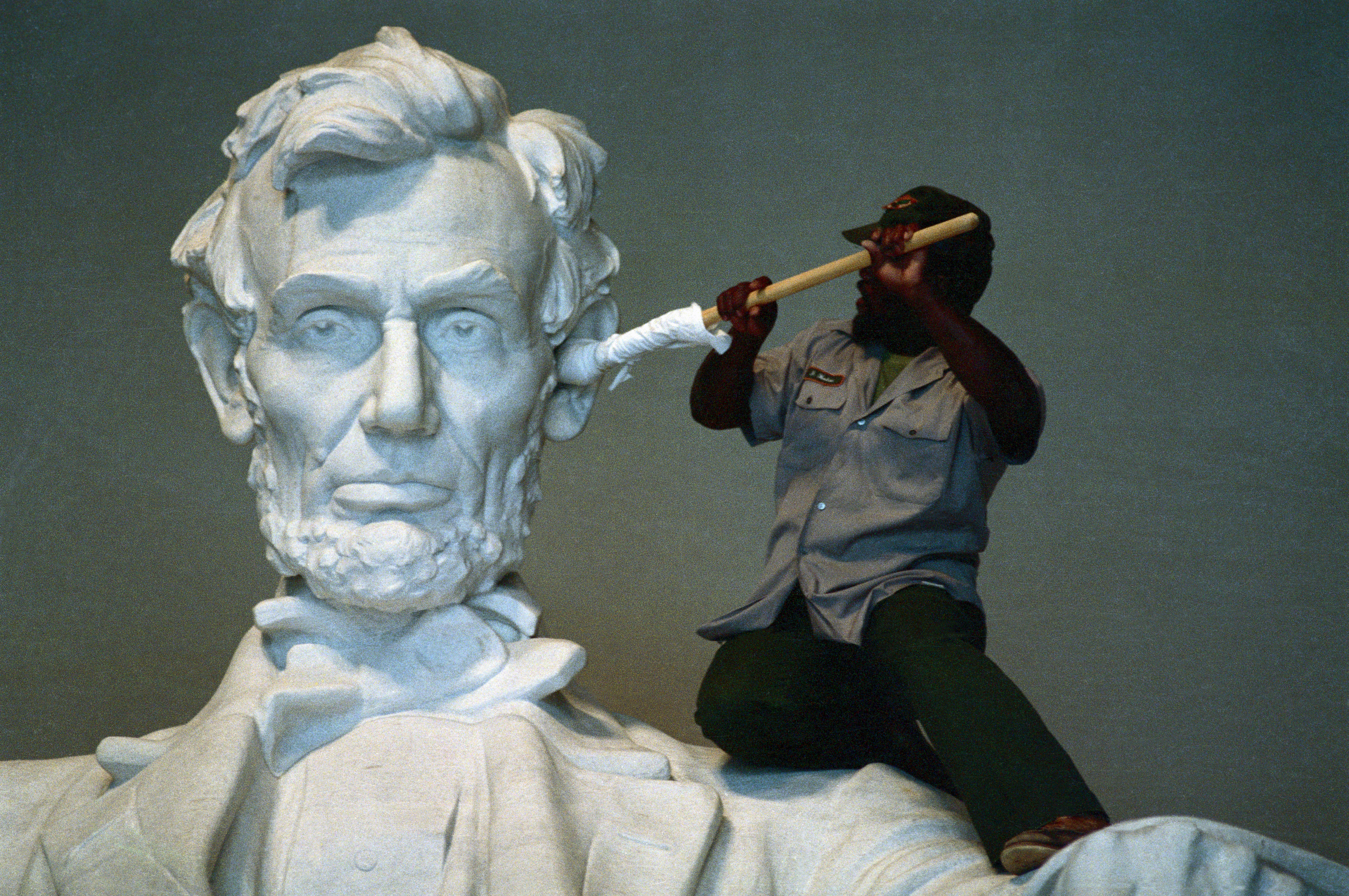

Take a look. These photos show the people who clean the ears of Abraham Lincoln (and other statues).

Watch. Friendship (out now in theaters) captures a “friend breakup” and the lengths to which one man will go to get his bro back, Shirley Li writes.

Stephanie Bai contributed to this newsletter.

Explore all of our newsletters here.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

The post The President’s Pattern of Impatience appeared first on The Atlantic.