The Oval Office clash between U.S. President Donald Trump and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky before a full-court media, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio stating that Ukraine is “not our war,” and Russian President Vladimir Putin’s acquiescence to any U.S. annexation of Greenland have increased speculation on whether the United States is jettisoning the decades-old model based on allies and partners and adopting a spheres-of-influence approach in its grand strategy. These signals have been buttressed by Trump’s recent speech in Saudi Arabia, in which the president rejected what he saw as previous U.S. presidents’ tendencies to “look into the souls of foreign leaders and use U.S. policy to dispense justice for their sins.”

The big promise with spheres of influence is the reduction, if not elimination, of the risk of world war. As great powers carve up the world, limit their defined interests, and respect one another’s backyards, they have less disputes and less reasons to engage in conflict. Or so goes the claim.

This promise should not be dismissed lightly. In our nuclear and hypersonic age, great-power wars count as among the existential threats to humankind. We are in a world more dangerous than the later phases of the Cold War in many respects. The last few years have seen growing risks of a direct Russia-NATO clash in Ukraine and a deterioration of security relations with China over Taiwan and the South China Sea, not to mention great power-magnified tensions in the Sahel and the Middle East. Arms control hangs by a thread, and the decline of unipolarity has Washington anxious. If spheres of influence dramatically reduce chances of a world war, that can only be a good thing.

But in the final analysis, spheres of influence cannot be the solution in our times. Washington’s conceptualization of its own sphere is too expansive and will not be acceptable to China; in an interconnected world, geographic partitioning is extremely challenging; and the global south is not what it once was and could resist such a configuration in direct and indirect ways.

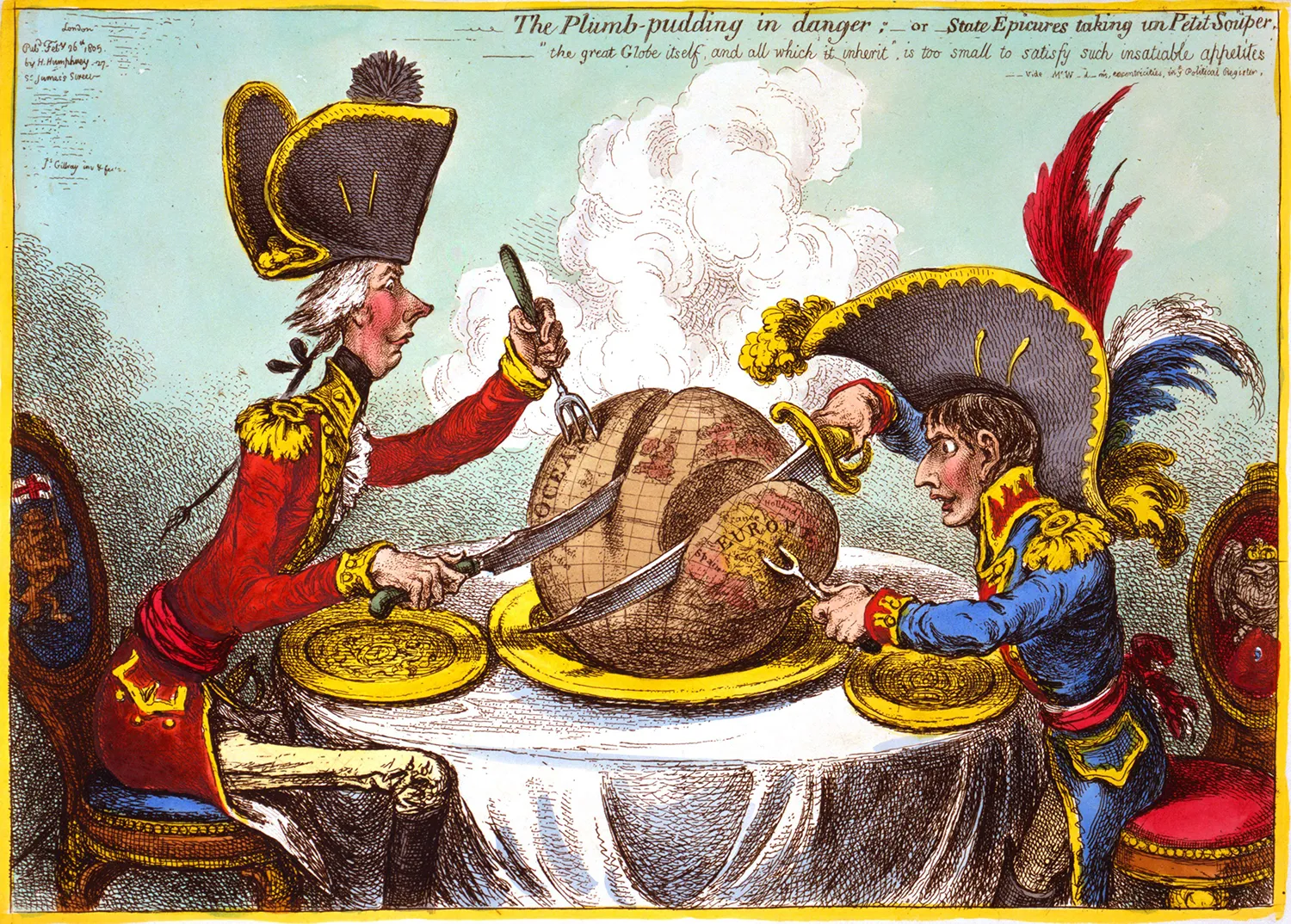

Spheres of influence are a type of great-power arrangement to order the world. Traditionally, they involve an implicit territorial partitioning among the great powers coupled with a shared understanding of how to maintain the arrangement and resolve differences. (The partitioning is about delineating zones of dominance, rather than merely influence, so perhaps “spheres of control” is a better name.) The term was first used in the context of the Great Game (a 19th-century struggle between the British and Russian empires), when in 1869 Russian diplomat Alexander Gorchakov assured Lord Clarendon, Britain’s foreign secretary at the time, that Afghanistan lay “completely outside the sphere within which Russia might be called upon to exercise her influence.” A series of great-power consultations had begun with the Congress of Vienna in 1814-15, followed by the infamous Berlin Conference of 1884-85, which apportioned Africa among European powers. These great-power concerts aimed to achieve a balance of power on the European continent as well as delineate zones of control in territories beyond.

In the current context, we can imagine an implicit partitioning scheme among the three great powers—the United States, Russia, and China—as follows: Washington would be preeminent in the Americas, Europe, parts of the Middle East, Japan, and Australia; Moscow in the Russian “near abroad”; and, perhaps, Beijing would hold sway in a part of East Asia and most of Southeast Asia. Other arrangements are also imaginable.

To be clear, the United States has no formal spheres-of-influence policy, and there’s unlikely to be a pronouncement to that effect anytime soon, if ever. But there are multiple signs that a very different grand strategy is being experimented with than during the decades of unipolarity since the end of the Cold War.

The Biden administration strived valiantly to maintain U.S. primacy. Though it occasionally gave a rhetorical nod to multipolarity, its policies on the ground were to maintain U.S. domination globally and in all dimensions of power: military, economic, and institutional. The new administration’s clearer acknowledgement of multipolarity is a promising beginning to reforming U.S. foreign policy.

Beyond more definitive rhetoric, the Trump administration’s policies are in keeping with this understanding of a multipolar world. Its skepticism toward multilateralism and globalism, near-elimination of foreign aid, embrace of territorial expansion in the Western Hemisphere, and willingness to cede a backyard to Russia are all major breaks from the past. After a short trade war, the United States and China have now announced what appears to be a breakthrough agreement. Previously, Trump himself has expressed skepticism about defending Taiwan and shown an eagerness for a grand bargain with Chinese President Xi Jinping. Trump has also shown a willingness for a nuclear arms reduction deal with Russia and China, with defense budgets on each side cut by half. And whereas former President Joe Biden played it safe and refused to reenter the Obama era-negotiated Iran nuclear deal, Trump has initiated major talks with Tehran that could avoid the specter of regional war in the Middle East and effectively recognize the country as a player.

While showing signs of dealmaking elsewhere, the administration has zeroed in on the Western Hemisphere as a focus; Rubio has spoken of it as a “common home.” The expressed desire to acquire the Panama Canal, Greenland, and Canada indicates that the United States is focusing on the Americas more intensely than it has in decades. These moves suggest a return to the Monroe Doctrine and perhaps even its 1904 Roosevelt Corollary, in which Washington arrogated itself the right to intervene in the Americas. In addition, Washington’s high tariff policies have treated Latin American states less harshly than most others—a nod toward a “Fortress Americas” model that creates both a place at the table for Latin American states and a buffer against Chinese encroachments.

If the United States were to limit its zone of domination to its backyard and a set of allies and partners in Europe and Asia, Russia and China would likely find it quite acceptable. But Washington’s gaze is turning out to be much broader. Trump’s lecturing of South African President Cyril Ramaphosa in the Oval Office on false claims of genocide of white South Africans was a deep intrusion into the sovereignty of Africa’s leading power. The Trump administration has also taken aim at the BRICS grouping and decided to boycott the upcoming G-20 summit in Johannesburg. And the prospect of control over valuable cobalt reserves probably explains its sudden interest in diplomatic mediation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Most recently, the United States is pressuring much of the world to exclude China from their economies using its tariff policy as a tool. U.S. Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth’s recent trip to the Philippines and Japan showcased continuity with the Biden administration’s focus of countering China in Beijing’s neighborhood. Manila is now an increasingly critical node in that strategy, which includes a focus on Taiwan. Last but not the least, Washington’s assertion on mining rights to valuable seabed resources in the international waters of the high seas—in contravention of the international norm—indicates that the United States may even be doubling down on its domination of the global commons.

Clearly, the United States’ desired sphere of influence ranges far and wide, well beyond its own hemisphere and core alliances. What we are likely witnessing is not an attempt for a roughly balanced partitioning of the world among the great powers but rather limited geographic and other concessions to Russia (and perhaps China, as signified by concessions in the recent trade deal)—all in pursuit of expanded U.S. control over important global minerals, supply chains, and key geographies across the global south as well as a souped-up domination of the global commons.

Would Moscow and Beijing be amenable to such a scenario? If its energy and defense sales are mostly unaffected, and an understanding reached with Washington over the Arctic, Russia will likely be reasonably pleased. After all, Moscow is the weakest of the three great powers, with a limited security horizon. But China has emerged as a peer competitor to the United States across practically all domains. Beijing is now a player with a truly global reach when it comes to trade, investment, technology, and supply chains. With the country’s rapid rise, China’s security perimeter of interest has also expanded. Beijing has long chafed at U.S. attempts to confine it to within the first island chain. China is unlikely to sign on to an assigned sphere of influence limited only to its coastal waters.

The great-power competition explicitly embraced by the United States in the first Trump term also securitized global trade and investment. This marked a rejection of the “flat world” thesis of the 1990s—the heyday of the unipolar era. Championed by geopolitical analyst Thomas L. Friedman among others, this theory posited that frictionless movement of goods, people, and ideas would increasingly be our future. Borders would become porous, arbitrage would drive economics, security would be collectivized, and Western military interventions would mainly be humanitarian. Instead, the revenge of geopolitics, inaugurated in 2017 with Trump’s first presidency, revealed the world to be lumpy rather than flat. Geography, along with nationalism and sovereignty, turned out to matter hugely.

But it would be a mistake to overcompensate for the errors of the flat world thesis and adopt the opposite view—that interdependence can be reconfigured at will, and at low costs, by powerful states. Trade, investment, and supply chains have gone so thoroughly global in the 21st century that it is hard to imagine even the current tariff war partitioning them neatly. When it comes to critical resources and manufactured products, no country is even close to self-sufficient.

Unwinding, reshaping, and stabilizing new supply chains along geopolitically preferred lines could take many years, probably decades, to realize, with significant scarcities and inflation as the price to be paid along the way. And many of these supply chains also run across the global south, which has also changed dramatically in recent decades.

The 19th century’s spheres-of-influence project was forged over the heads of a mostly colonized global south, which had practically no say in how the great powers of the day determined the destiny of its various peoples. But a contemporary great-power concert to carve up the world will be greatly resented by the wide swath of developing states stretching from Mexico City to Manila. And the difference today is that some of them can do something about it.

More than five decades after decolonization, the global south’s middle powers take great pride in their hard-won autonomy. They have become savvier through the socialization induced by globalization. Most now also have major regional reach. They don’t have the power to reorder the world to their liking. But they do have ways of complicating the spheres-of-influence project. And it is quite likely that many of these states, while they face short-term headwinds due to Washington’s strategic shift, will emerge more resilient in the longer term.

In the shorter term, there is no doubt that the shifts in Washington are bad news for the global south, even among its most dynamic regions. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) could lose a quarter of its projected growth over the next couple of years due to new U.S. trade barriers. The so-called least developed countries, most of them in Africa, could suffer greater humanitarian crises and increased instability.

On the surface, global south states, from Mexico to Vietnam, have responded to America’s turn away from globalism on an individual, not collective, basis. But the stream of government delegations making a beeline for Washington is less a sign of surrender than an indicator of the inherent pragmatism of the new global south. Countries within it want to limit the damage from this new protectionism.

On the other hand, the world is better prepared to weather Washington’s trade revolt than it would have been in the 1990s; the world trading order is already multipolar and getting more so. For instance, ASEAN’s fraction of exports to the United States has steadily reduced since 2000 from about 24 percent to now under 15 percent. In Africa, the United States accounts for only a small fraction of its exports when measured against African imports.

Washington is now widely perceived to be an unreliable partner, and longer-term cost-benefit calculations of global south states have radically changed as a result. Unreliability and volatility will naturally energize strategies of diversification. The appeal of new economic poles—ASEAN, India, Turkey, and the Gulf states, among others—has dramatically increased, even as established middle powers such as the European Union, Canada, and Japan continue to act as stabilizers of the global trading system.

Global south states do not favor either a new cold war between the great powers or a sphere-of-influence carve-up of the world. A strategy of hedging has long been their response. But now Washington is using the tariff tool to force countries to exclude China.

One logical response to this test is bandwagoning. Global south states could choose either the United States or China (or Russia in a few cases) as their chief geopolitical anchor. If bandwagoning became the new trend in the global south, this would be a shot in the arm for a spheres-of-influence world. But Washington may not end up as a net beneficiary. Despite the wariness of some global south states (especially in Asia) toward Beijing, many could end up picking China as the lesser of two risks, if forced to make a choice. Beijing is already among their biggest economic partners and can now also sell itself as being more dependable than Washington.

There is also the intriguing possibility that global south states avoid picking a single great-power patron and instead turn toward deepening ties with one another. This could take the form of stronger regional architectures. Chile and Brazil are leading this charge in Latin America. But it is in Asia where regionalism could truly thrive, with ASEAN already a successful example. In recent weeks, ASEAN, China, Japan, and South Korea have announced a strengthening of their regional financial stability mechanism, the Chiang Mai Initiative. The Philippines, threatened by illegal Chinese incursions, continues to see the United States as its core ally. But Manila is increasingly deepening security partnerships with other Asian powers as long-term insurance against U.S. volatility.

Cross-regional integration, currently very weak, could also get a fillip. The fast-expanding BRICS, an interests-driven coalition between Russia, China, and a set of global south states, could be the hook for such integration. Its rapid expansion and growing attraction are a demand signal for plugging acute failures in the international system. BRICS is not designed to be, and will never become, a security club. But with the United States perceived as an unreliable partner, geopolitical cooperation beyond narrower economic issues is emerging as a common interest for BRICS’s middle powers.

While spheres of influence largely kept peace in Europe for most of the 19th century, the arrangement did not last. As states rise, their interests expand. When a new state—Germany—rose and tried to become a great power, Britain and France could not tolerate it. The resultant disputes, fought over the colonies, acted as major destabilizers. Sordid deals such as the Berlin Conference delayed the denouement but not for long. The concert’s collapse unleashed a horrific world war in 1914.

If territorial control and partitioning became the new benchmark of power and success, any prior understandings between today’s great powers could be short-lived. There are several middle powers in the current order whose ambitions will naturally expand as they rise. Some may even desire their own enhanced zones of control. The promise of peace in a new spheres-of-influence world may ultimately also be illusory.

The post Spheres of Influence Are Not the Answer appeared first on Foreign Policy.