Charles B. Rangel, the former dean of New York’s congressional delegation, who became the first Black chairman of the powerful House Ways and Means Committee, only to relinquish that position when he was censured for an ethics violation, died on Monday. He was 94.

His death was announced by his family. The announcement did not say where he died.

A mainstay of Harlem’s Democratic old guard, Mr. Rangel was first elected to Congress in 1970, toppling the raffish civil rights pioneer Adam Clayton Powell Jr., a 13-term incumbent. He went on to serve in the House longer than any other New Yorker but one: Emanuel Celler, who represented Brooklyn for nearly 50 years until his defeat in 1972.

Mr. Rangel retired in 2016 after winning a 23rd term despite the ethics allegation — making him the ninth-longest continuously serving member of the House in American history.

In 2000, he was instrumental in persuading Hillary Clinton to enter electoral politics by running for the Senate from New York when Daniel Patrick Moynihan retired.

Mr. Powell’s absences from Washington and his refusal to pay a slander judgment had prompted the House in 1967 to strip him of a committee chairmanship and exclude him from Congress. A decade later, Mr. Rangel also got caught up in an ethics investigation.

Mr. Rangel had successfully lobbied to become the first Black member of the Ways and Means Committee in 1974, and to win the chairmanship in 2006 when Democrats regained control of the House. But he was forced to give up the gavel early in 2010 after the House Committee on Ethics admonished him for violating congressional gift rules by accepting corporate-sponsored trips to the Caribbean.

On Dec. 2, 2010, at the age of 80, Mr. Rangel stood silently in the well of the House of Representatives as Speaker Nancy Pelosi meted out the censure verdict, delivered by a vote of 333 to 79.

He was the 23rd member of the House to be censured and the first in nearly three decades. Exactly one month earlier, even with the charges pending, he had been overwhelmingly re-elected by his constituents in Manhattan and in enclaves of the Bronx and Queens.

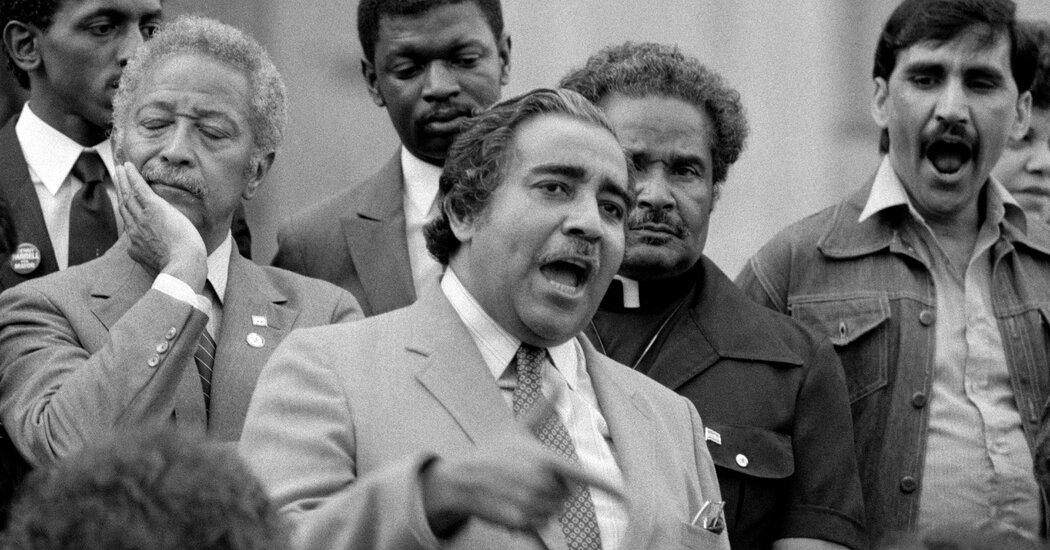

Mr. Rangel was the last surviving member of the venerable group of Harlem elder statesmen known as the Gang of Four. The others were David N. Dinkins, the city’s first Black mayor; Percy E. Sutton, the former Manhattan borough president; and Basil A. Paterson, who was a state senator and secretary of state, and whose son, David Paterson, was lieutenant governor and then interim governor of New York from 2008 to 2010.

For decades, the closest anyone had come to unseating Mr. Rangel was in 1994, when he handily defeated a son of Mr. Powell’s. But by 2012, as the 13th District’s political center of gravity had edged north from Harlem toward a Dominican enclave in the Washington Heights section of Manhattan, he was threatened for renomination by State Senator Adriano Espaillat. Mr. Espaillat went on to succeed Mr. Rangel in 2016 after the congressman decided not to seek re-election.

Mr. Espaillat’s victory ended the Black political establishment’s grip on a congressional district that had been represented by an African American since Mr. Powell was first elected in 1944. And it affirmed the gradual shift in the city’s Black power base from Harlem to Brooklyn.

People often disagreed with Mr. Rangel. His long years in office and perhaps a sense of entitlement prompted rivals to accuse him of taking his congressional constituents for granted. But hardly anyone disliked him.

Mr. Rangel, who was a roly-poly 5-foot-11 (he once quipped that he had lost 5,000 pounds in a life of on-again, off-again dieting), was known for his sculpted mustache, his raspy, adenoidal voice and his Cheshire-cat grin. He was Charlie to constituents and to colleagues who, had there been a congressional yearbook, would have voted him Mr. Conviviality.

Except perhaps during Mr. Dinkins’s four-year term as mayor of New York, from 1990 through 1993, and even during David Paterson’s stint as governor after Eliot Spitzer resigned in 2008, Mr. Rangel was arguably the most powerful Black elected official in the state.

“I’m a successful politician who more than happens to be Black,” he once said.

Although he ventured politically beyond Harlem only once, unsuccessfully seeking the Democratic nomination for City Council president in 1969, he won re-election with monster margins in a district where, by 2010, only about one in three residents was Black.

And in the 2004 presidential election, Mr. Rangel’s constituency generated the largest margin of Democratic votes for John Kerry — more than 90 percent — of any congressional district in the country.

Harlem Born and Bred

Charles Bernard Rangel was born in Harlem on June 11, 1930, the second of three children. His mother, Blanche Mary (Wharton) Rangel, whose family was from Virginia, was a seamstress and a domestic worker. His father, Ralph Rangel, who was born in Puerto Rico, was often unemployed and abusive and left home when Charles was about 6.

Early on, Charles’s career path did not appear to be promising, either. He often skipped school, but his maternal grandfather, an elevator operator at the Criminal Courts Building downtown, helped keep him from getting into worse trouble. It was his grandfather’s desire to continue working beyond the mandated retirement age of 65 that introduced Mr. Rangel to politics.

“I had to go hat in hand to the neighborhood Democratic political club to plead for an extension,” he recalled in his 2007 memoir, “And I Haven’t Had a Bad Day Since: From the Streets of Harlem to the Halls of Congress,” which he wrote with Leon Wynter. Making a case for his grandfather to the district leader, whose influence extended to patronage appointments in the Criminal Courts, provided Mr. Rangel with his first taste of “how dealing with powerful people gets things done, and might make you powerful, too.”

He attended Harlem public schools but dropped out of DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx to enlist in the Army in 1948. He fought in the Korean War, where, while wounded by shrapnel from a Chinese shell, he led his all-Black unit to safety from behind enemy lines at Kunu-ri. He won a Bronze Star for valor but was self-effacing about the honor: “I appeared to be less scared than the 43 enlisted men who followed me.” He was only a private at the time; he left the service as a staff sergeant.

His experience that day helped inspire the title of his autobiography.

Mr. Rangel returned to school after the war and enrolled in New York University, where he made the dean’s list and graduated in 1957. He went on to St. John’s University Law School, graduating in 1960. The next year, he was hired as an assistant United States attorney in Manhattan, where he served under Robert M. Morgenthau.

In 1964 he married Alma Carter, a social worker, whom he had met at the Savoy Ballroom in Harlem. His wife died before him. He is survived by their son, Steven; their daughter, Alicia Rangel Haughton; and three grandsons.

Also in 1964, he entered into a political marriage that would endure nearly as long, when he and Mr. Sutton, a member of the State Assembly, organized the John F. Kennedy Democratic Club. When Mr. Sutton became Manhattan borough president, Mr. Rangel ran for his State Assembly seat. In 1966, he was elected to the first of two terms.

In 1970, in a squeaker Democratic primary, Mr. Rangel dislodged Adam Clayton Powell Jr., who had been accused of growing remote from his constituents.

The district was reconfigured several times at its fringes — it now includes East Harlem, Washington Heights, the Upper West Side and a slice of Astoria, Queens — but its cornerstone remained Central Harlem, including the house where Mr. Rangel grew up and the Lenox Terrace apartment where he lived at his death.

Politically Nimble

As a congressman, Mr. Rangel impressed his colleagues with his gregarious political agility and his impishness. He was able to forge alliances without betraying his bedrock liberalism or his urban roots, and to deftly deliver a biting remark without drawing blood.

When a group of Texans was testifying before his committee, Mr. Rangel couldn’t help commenting on how courteous they were to one another.

“I notice you all call each other Colonel,” he said. Yes, one of the Texans explained, the title was an honorary one, and he offered to bestow it on Mr. Rangel, too. The congressman replied, “Sure beats ‘boy.’ ”

Years later, after Vice President Dick Cheney singled out Mr. Rangel’s elevation to the Ways and Means chairmanship as evidence of a Democratic tax-and-spend agenda, Mr. Rangel professed surprise. “He doesn’t normally get involved with any of this tax stuff,” Mr. Rangel said of Mr. Cheney. “He’s just war, war, war.”

Mr. Rangel said that winning his seat on the tax-writing Ways and Means committee was not easy, but that it was important to his state, his city and his constituents.

“Oh, my God, I had the support of Governor Rockefeller and Mayor Lindsay to get on Ways and Means,” he recalled in 2016. “They were telling me I had to get on the committee to help the city. I got on to fill the vacancy left by Hugh Carey when he ran for governor.”

He said he endorsed Mr. Carey for governor only after Mr. Carey agreed to lobby his congressional colleagues to support Mr. Rangel as his successor on the committee.

Mr. Rangel was content to remain in Congress, biding his time as he rose in seniority and occasionally playing the role of kingmaker.

He participated in the Judiciary Committee’s Watergate hearings, which led to the resignation of President Richard M. Nixon; sought to stem the influx of illegal drugs as chairman of the Select Committee on Narcotics Abuse and Control; and used his leverage on Ways and Means to create empowerment zones for economic development, expand the earned-income tax credit, promote a tax credit for affordable housing, pump more Medicare money into New York hospitals, and widen opportunities for trade with Africa and the Caribbean.

Mr. Rangel was sometimes accused, usually by liberals, of being too pragmatic. But he rarely shied away from being provocative.

He repeatedly introduced legislation to abolish the all-volunteer Army. “There’s no question in my mind,” he said in 2006, “that this president and this administration would never have invaded Iraq, especially on the flimsy evidence that was presented to the Congress, if indeed we had a draft and members of Congress and the administration thought that their kids from their communities would be placed in harm’s way.”

In a world of arcane tax policy, in which a single word could generate millions of dollars in profits to industry and to campaign coffers, Mr. Rangel developed a reputation for being “an eloquent listener,” as one lobbyist put it.

But the ease with which Mr. Rangel maneuvered through the system raised questions about whether he had also manipulated it.

In 2010, he was investigated by the Ethics Committee for allegations that he failed to pay federal taxes on $70,000 in rental income from a home he owned in the Dominican Republic, and for his use of several rent-stabilized apartments in a Harlem building provided by a real estate developer. He had moved into the building well before Harlem’s revival as a residential neighborhood.

The New York Times reported that he was paying below-market rent for the apartments, despite rules prohibiting House members from accepting gifts worth more than $100.

The investigation was expanded to include amendments to his House financial disclosure statements indicating that he had failed to report hundreds of thousands of dollars in income and assets from 2002 through 2006; they included an investment account valued at $250,000 to $500,000, tens of thousands of dollars in municipal bonds, and $30,000 to $100,000 in rent from a multifamily brownstone he owned.

Investigators also explored whether he had improperly used his office to raise money for a charity — the Charles B. Rangel Center for Public Service at the City College of New York — from donors who had business before his panel.

A Painful Reminder

Mr. Rangel attributed the lapses mostly to accounting errors; he said he had never intended to evade taxes or profit unfairly. But a House subcommittee found him guilty of 11 of the 12 improprieties with which he was charged, and his colleagues, rejecting a lesser reprimand, voted for censure.

The accusations embarrassed his fellow Democrats, forced him to step aside as committee chairman, and sorely tested his good humor. Until the end, he kept an improbable painting hanging in his Washington office: a portrait of his deposed predecessor, Adam Clayton Powell Jr. It was, Mr. Rangel explained, “a reminder of what can happen in Washington.”

He all but acknowledged, though, that the ethics charges would indelibly blemish that judgment. “Sixty years ago,” Mr. Rangel said as the charges were formally lodged, “I survived a Chinese attack in North Korea, and as a result I wrote a book saying that I hadn’t had a bad day since. Today, I have to reassess that statement.”

“The older I get, the more I think of how I can make my case with St. Peter in order to get into heaven with some decent accommodations,” he wrote in his memoir. “I’ve spent all of my life preparing this case.”

“If St. Peter’s not overly impressed with my legislative record,” he added, “then I’ll just have to tell him that I did the best I could.”

Moments after he was censured in 2010, Mr. Rangel told his colleagues: “I know in my heart I am not going to be judged by this Congress. I’ll be judged by my life in its entirety.”

Remy Tumin contributed reporting.

Sam Roberts is an obituaries reporter for The Times, writing mini-biographies about the lives of remarkable people.

The post Charles B. Rangel, Longtime Harlem Congressman, Dies at 94 appeared first on New York Times.