Few world leaders have taken up the job so late in life yet have so little experience. Few can have won an election and been so unpopular even on victory. Few can have faced the enormity of the challenges that Friedrich Merz faces with so little confidence among his citizens that he can meet them.

Germany’s 10th postwar chancellor is only weeks into office, but judgments were being made about him even before he took over. Most of these are influenced by a national propensity to see the glass as half-empty. Yet, at the age of 69, Merz knows he doesn’t have long to make a mark.

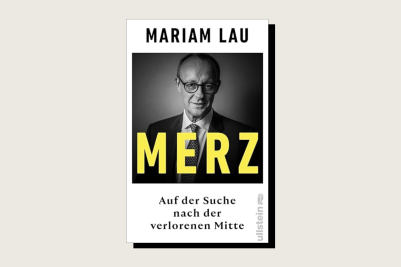

Who exactly is he? A spate of biographies, published early in the election campaign, shed a little light. A new book adopts a different approach. Mariam Lau, a journalist at the weekly Die Zeit and one of the most authoritative experts on German conservatism, takes a thematic approach in Merz: Auf der Suche nach der verlorenen Mitte. She seeks to explain how Merz will deal with the likes of Presidents Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin and how he’ll try to kick-start the German economy. She asks whether he has a problem with women (he has been accused of being patronizing or sexist) and whether he would be ready to wage war for his country.

Lau begins by probing his past and a grandfather whose prominent support for the Nazis is being increasingly chewed over in the media; it is making the requirement even more urgent that Merz succeeds in the task he has set himself—to distance his Christian Democrat-led government from the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) while differentiating it from the legacy of former Chancellor Angela Merkel.

The picture emerging of Merz is of a man whose flaws are open for all to see but whose resilience is underestimated. The subtitle of Lau’s book—“The Search for the Lost Center Ground”—makes clear that this is the direction in which he wishes to head. Yet, if that is so, he sometimes has a strange way of showing it. As Lau writes, Merz has a track record of getting himself in trouble. “One could almost speak of the ‘Merz Disease,’” she writes, “airing a resentment, doubling down on it when faced with headwinds, only to have to give in at some point.”

The author seeks to disentangle two extraordinary U-turns that Merz took during the election period. Having said he would never deal with the AfD, in late January he submitted a motion in the Bundestag, Germany’s parliament, advocating a clampdown on immigration, knowing that the only way it would pass would be with support from the far right. The bid failed because of a rebellion from furious MPs within his own ranks.

A few weeks later, having insisted that he would not contemplate loosening the “debt brake” that severely restricted public borrowing, he did just that. By a sleight of hand, he used the outgoing parliament to pass a constitutional change allowing for a huge injection of money for spending on defense and public infrastructure. He was now denounced by all sides as untrustworthy, too. Lau contends that he had little choice but that he could have acted earlier. The execution may have looked unprincipled, but Germany has ended up in a better place—finally giving itself the tools to grow and modernize.

The first about-turn had no such caveats. It was an unmitigated disaster, one that has left a lingering suspicion about his relationship to the AfD. Some of Merz’s allies want to remove the “firewall” that rules out cooperation with the party at the regional and national levels. He insists he will not do so.

Instead, he wants to weaken the appeal of the far right by dealing with its signature issue—immigration. On day one of his leadership, he instructed Interior Minister Alexander Dobrindt to impose border checks and to turn asylum-seekers away at the border. Whether it succeeds in bringing down illegal migration or increases confidence in the state’s ability to control overall figures—rather than being purely performative (there’s little stopping people trying again and again to get in)—is another matter. His partners in the coalition, the Social Democrats, are prepared to go along with it.

Far more open is the approach to the economy. The Social Democratic Party has watered down Merz’s commitments to cut Germany’s generous welfare payments or to countenance other radical reforms to the tax code or pensions system. As Lau notes, the entire structure of modern Germany was based on stability and on removing the opportunities for leaders to seize untrammeled power. The Basic Law (the constitution enacted in 1949) ensured that coalitions were required to be formed at all levels of government; power was shared, only involving moderate parties, and the regional states enjoyed considerable autonomy. Leaders such as Konrad Adenauer, Germany’s first postwar chancellor, “stood for a break with all things ideological, as well as for stability, reconciliation, a longing for normality and democratic boredom.”

It was in that spirit that Merkel also navigated her 16 years in power, seeing the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) as the party of small steps. She and Merz fell out early—each accusing the other of undermining them. She publicly attacked his parliamentary flirtation with the AfD. He has regular trashed her legacy and what he calls her “asylum-hugging” and “green-hugging.” Merkel recently tried a gesture of reconciliation, appearing as a visitor to the Bundestag to watch Merz’s confirmation as chancellor, only to witness him suffering the ignominy of becoming the first candidate to be voted down. By the time he was elected in a second ballot a few hours later, she was gone.

Lau quotes another writer on conservatism, Edmund Fawcett: “‘[C]onservatives have largely created and learned to dominate a liberal modern world in which they cannot feel at home.’” She continues: “The question of how the insistence on tradition and attachment to one’s homeland are compatible with creative destruction, without which there would be no prosperity and no free market economy, for example, is one that an economic liberal like Friedrich Merz must ask himself.” This goes to the heart of the Merz problem, indeed a problem facing all mainstream center-right parties: How do they reconcile traditionalism with the need for change?

With the British Conservatives languishing in fourth place in opinion polls, and similar parties floundering, is the only route to success the one taken by the likes of Trump—a mix of maximum economic and democratic disruption alongside a so-called return to traditional social values?

Until recently, Lau notes, Merz hated being called a conservative. If he was to be given that moniker, he demanded that the word “progressive” be added to it. Anything else would be seen as “unsafe” or tending toward the extreme. Now, she says, it has gone from a term of abuse to a badge of pride. At the same time, he must run a centrist coalition (roughly where all German governments end up), leaving him open to pushback from the left and fury from the right.

There may be a way through, she suggests, one that can align the different factions: “Merz is also an enthusiastic modernist, in the technological sense. Fusion reactors, carbon dumping in the ground, space travel, mRNA vaccines—the CDU leader is an enthusiastic supporter of the idea that a country like Germany, which is poor in raw materials, should draw much more growth from its wealth of inventions.”

This will not be easy. Old habits, such as a reluctance to embrace digitization and an overreliance on bureaucracy, are embedded. Will Merz take risks to modernize the country? In his speeches so far, he seems to have tended in both directions: in some, seeking to reassure, in others, not shying away from controversy—such as suggesting workers don’t put in enough hours.

Lau also notes a very German set of cliches associated with Merz that will likely always pose a democratic obstacle: “The old white man; the rich, ruthless man; the neoliberal; the unpopular man—behind this dreary folklore lies the rock-solid conviction of many Germans that it is ultimately simply not OK to be right-wing, politically relevant, and then also rich.”

Merz may well do what other leaders have done when confronted by domestic resilience—devote most of their tenure to foreign affairs. He certainly has much on his plate and has already shown dexterity. He has responded quickly to the denunciations of Germany and Europe by senior figures in the Trump administration by making clear the need not just for rearmament but for a new approach to European self-reliance. His overtures to Paris, London, and Warsaw were striking, and the continent’s new security inner core has shown commendable unity toward Ukraine.

Far less certain, and far less commendable, has been Germany’s refusal to countenance any significant criticism of Israel’s near-destruction of Gaza. Merz is following Merkel and others in their guilt-laden paralysis on the issue; indeed, his embrace of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is all the more pronounced.

Lau concludes with the following exhortation: Merz, she says, “is a conservative in an era of authoritarians who must earn the title ‘conservative’ again and again because he occasionally squanders it.” The German business model, with cheap energy from Russia, the Chinese sales market, and the U.S. security guarantee, has hit the wall. The rules-based international order is in tatters; military experts call the current phase “prewar.” She quotes him as saying, “The political center is capable of solving problems.”

With the center cracking all over the Western world, the task the new German chancellor faces is unenviable.

The post Can Friedrich Merz Save Conservatism? appeared first on Foreign Policy.