By the art world’s own accounting, the spring auction season fell short of even its lowest target. Reaching for a combined estimate from $1.2 billion to $1.6 billion, the three major auction houses fell short at $1 billion when excluding the hefty buyer fees that inflate their totals.

Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Phillips all underperformed their own estimates, which the companies had previously said were conservative predictions based on a market that has continued to decline over the last three years. Analysts placed the blame largely on an uncertain global economy and the changing tastes of collectors.

Art stars flopped or sold below expectations in auctions that were stressful to watch. A $70 million Giacometti sculpture went unsold despite four minutes of coaxing from a desperate auctioneer. A $30 million Warhol painting was yanked mid-sale when the consignors realized nobody would pay its asking price. A radiant Mondrian painting with a pre-sale estimate of about $50 million scooted to the finish line when a single bidder, presumably its guarantor, paid $47.6 million, including fees.

“We saw estimates not reflecting where the market was, but reflecting what the auction house’s agreement was with the consignor,” said Natasha Degen, the chairwoman of art market studies at the Fashion Institute of Technology. “Maybe this isn’t the time when people want to acquire record-breaking trophy work.”

Bonnie Brennan, the chief executive of Christie’s, said she hoped for a stronger auction season in the fall. “Our market is one that thrives on stability,” she said. “We are just in a time of great uncertainty.”

As reasons for optimism, she pointed to records set for women and a handful of artists of color; an impressionist painting by Monet that sold for nearly $43 million, including fees, after a five-minute match among three bidders; and energetic wrestling for artworks priced at $7 million and below.

But after several years of declining sales, the art market is trying to lower the benchmark for success as it experiences thinner bidding from collectors, with lower price points. Here are five major trends from this auction season that define the art market’s current downturn.

Lowering Expectations and the Price Ceiling

Last May, 12 paintings sold for more than $20 million each, after fees, across Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Phillips’s marquee spring sales. Only six lots sold in that price range last week, all of them at Christie’s.

It was already a step down from previous years, when $50 million paintings were the measure of success, thanks to historic artworks coming out of estates, offered to buyers who enjoyed a booming financial market and low interest rates. But not a single artwork sold for $50 million or more this season, though two carried estimates at that level.

There was also some evidence of price depreciation, which could affect collectors motivated by the idea that artworks consistently outperform the stock market as an investment vehicle. Not including changes in inflation, which would increase the gap between the prices, here are three examples of falling values in repeat sales:

-

A painting of a cover girl by Kerry James Marshall from his celebrated “Pin-Up” series that sold for $5.5 million in 2019 decreased in value by 30 percent, fetching $3.8 million at Christie’s on Monday.

-

A painting by Lucio Fontana that sold for nearly $14 million in 2017 decreased in value by 46 percent, selling for $7.5 million at Christie’s in the same sale.

-

A Baroque egg sculpture by Jeff Koons that sold for $6.2 million in 2011 decreased in value by 63 percent, bringing only $2.3 million at Sotheby’s on Thursday.

Brennan, of Christie’s, said that new material typically performs best at auctions. “Freshness is always one of the key measures of success,” she said. “Collectors love discovery.”

Karina Sokolovsky, a spokeswoman for Sotheby’s, also pointed to examples of works by artists who have appreciated in value after longer periods of holding, such as a Willem de Kooning painting that was last offered in 1993 for $222,500 that sold for $3.2 million on Tuesday, and an Ed Ruscha work that sold in 2009 for $1.8 million that returned to auction last week for $7.8 million.

Signs That Postwar Masters Are Losing Their Audience

Many of the blue-chip brand names disappointed this season, despite a marketing push from executives that emphasized a “flight to quality” after several years of financial speculation on young artists.

But the flight might have landed the auction houses in the bargain bin. Frank Stella, Ellsworth Kelly, Franz Kline and Robert Motherwell all hammered at or below their low estimates — or went unsold.

“There are definitely not many new buyers who are as keen on some of these American masters,” said Morgan Long, an art adviser based in London, while noting that Mark Rothko, Roy Lichtenstein and Alexander Calder “are still hugely popular internationally with a wide demographic.”

“We are looking at a distinct generational market shift as more of these works come to market from American collections and garner very thin interest,” she added.

That shift has become apparent in the Warhol market, which rarely produces the mega-sales it once did. Experts have said the artist’s most consequential works are held in private collections and by museums that are reluctant to sell.

“There are certain artists where their values have stayed consistent, sometimes for 10 or 20 years,” said Robert Manley, an executive at Phillips. “They’re good artists to buy because they hold their value.” But as for the growth potential, he added: “If it hasn’t happened in the past 10 years or so, chances are that it might not happen in the next 10.”

Female Artists Provided a Spark

Still surprisingly undervalued were works by women — of all ages and ethnicities.

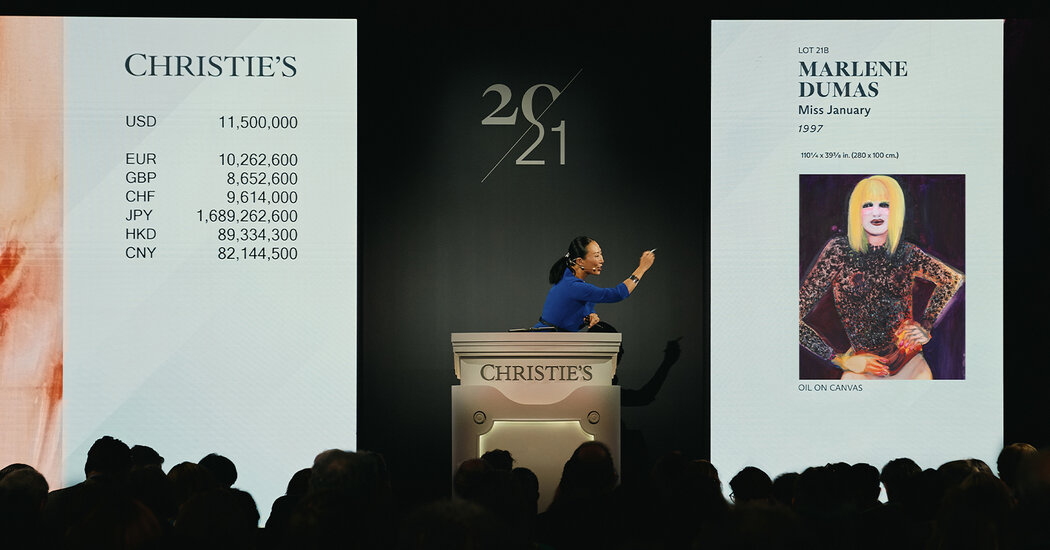

Marlene Dumas’s 1997 portrait “Miss January,” which sold for $13.6 million with fees in Christie’s 21st Century evening auction on May 14, came close to achieving the highest price for an auctioned artwork made by a living female artist, falling just short of the record set by Jenny Saville in 2018 when that $12.4 million sale is adjusted for inflation to about $15.8 million.

The achievement for Dumas, still active at age 71, was preceded one day earlier by a new auction high for the genre-bending 93-year-old artist Olga de Amaral. Bidding drove “Imagen Perdida 27 (Lost Image 27),” a shimmering abstract textile from 1996, to just under $1.2 million at Phillips on May 13; another of her works, “Imagen Paisaje 26 (Landscape Image 26),” sold for only $25,000 less in a Sotheby’s sale 72 hours later.

New top prices were also reached for the female Surrealists Dorothea Tanning and Remedios Varo; the American Abstract Expressionist Grace Hartigan, who died in 2008; and the Austrian-born Pop artist Kiki Kogelnik, who died in 1997. Among the contemporary American women, the renowned sculptor Simone Leigh set a personal record at auction, as did ascendant female artists younger than age 40, including Emma McIntyre and Ilana Savdie.

Except for the Dumas painting, all these lots — as well as three paintings by Danielle Mckinney — surpassed their high estimates thanks to lively bidding, a stark contrast to the subdued, and often nonexistent, competition for many canonical male artists.

Degen, of F.I.T., noted that the female artists in Phillips’s evening sale who did “distinctly better” than their male counterparts “covered the gamut from ultracontemporary to rediscoveries to the more canonical names.”

“Maybe there is a sense they are more competitively priced,” she added.

Tariff Woes and Global Economic Instability Hurt After All

Executives believed that the spring sales were going to be troubled months ago, when senior executives told reporters that they were already focusing on their consignments for November auctions.

In the lead-up to last week’s sales, some of the same executives gamely suggested that the supply pipeline had unfrozen. But now it is clear that the Trump administration’s tariff policies sent a chill through the international art market.

“It did impact us in terms of not being able to get a couple of consignments,” Manley, of Phillips, said. “The tariff uncertainty moment lasted 10 days or so. That was really crucial. It’s one of the reasons our sale was a bit smaller than it is normally.”

Phillips had one of its smallest sales in recent memory with its top seller — a 1984 Basquiat painting once owned by David Bowie — going for just $6.6 million with fees. (Last year Phillips sold a higher-quality Basquiat for $46.5 million.) Its total sales for the week plateaued at $73.5 million with fees, down about one-third from the nearly $110 million it generated in equivalent auctions last May.

There was also a noticeable absence of bidding by Asian collectors, who have been a propulsive force in the art market for 40 years. But the struggling Chinese economy and President Trump’s ongoing trade war with President Xi Jinping have hurt the pocketbooks of the ultrawealthy.

According to information from the auction houses, Asian collectors generally accounted for more than a third of all sales only a few years ago. This season, for example, only 10 percent of buyers in Sotheby’s Modern evening sale on May 13 were from Asia.

Success Is Not About Selling Well. It’s About Selling at All.

Auction houses are trying to reset expectations after two years of declining sales by boasting of their “high sell-through rates,” meaning they sold 80 percent to 90 percent of what they offered, though this year it was often through guarantees.

The security of a dependable sale has replaced thrilling risk.

“When you have a billion-plus-dollar week in one of the major sales, with healthy sell-through rates, that’s compelling,” said Charles Stewart, the chief executive of Sotheby’s, when asked how he defined success this season.

Even the failure to sell a $70 million Giacometti can be spun into a positive: Stewart, in a statement, described it as “a real auction moment” with “no financial engineering behind it.”

Unable to celebrate a record for a painting by Claude Monet, Christie’s promoted a record for the artist’s poplar trees. The auction house also celebrated an obscure German Symbolist named Franz von Stuck, who achieved a record for a work on paper. And Sotheby’s cheered for a light switch sculpture made by Claes Oldenburg.

All of these are signs of an art market working hard to stay where it was before the spring’s major auctions: in flux, but alive.

Zachary Small is a Times reporter writing about the art world’s relationship to money, politics and technology.

The post New York’s Spring Auctions Aimed for Trophies. They Got Troubles. appeared first on New York Times.