In the opening scene of Spent, billed on its cover as a “comic novel,” Alison Bechdel’s cartoon avatar, also named Alison, has rearranged her sock drawer in an effort to stave off “the feeling of impending doom.” Ever since she was born on the page four decades ago, Bechdel’s fictional self has regularly journeyed between insecure and panicked, conveyed by the artist through subtle downturns in her tiny dash of a mouth. She perseverates about impending nuclear war, environmental disaster, “patriarchal death culture,” girlfriends cheating on her, the local gay bookstore where she works closing down.

For fans who have followed Bechdel from underground lesbian cartoonist in the 1980s to best-selling author of Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic, and then watched with amazement as her life on the page went 3-D in a multiple–Tony Award–winning musical, the doom-tinged update in Spent will not come as a shock: She can still get pretty freaked out.

Bechdel’s latest title refers to late-stage capitalism, the semi-facetious frame for the book (which is broken into “episodes” titled “The Commodity,” “The Process of Exchange,” and so on), but like almost everything else in her graphic storytelling, the title is also self-referential: It describes her age and her state of exhaustion, and perhaps hints at a concern that aging lesbians might not command much of an audience. Cartoon Alison now has lines under her eyes and graying hair, though otherwise she looks more or less as she did 40 years ago: butch haircut, eyes wide and worried, hunched shoulders, and, even in her 60s, the air of a teenage boy who does and doesn’t want to be picked for the team.

So imagine my surprise when, toward the end of Spent, after Alison has suffered through months of writer’s block, a public-speaking flop, an awkward trip to Hollywood, an encounter with her Donald Trump–loving sister, and a couple of anxiety dreams, I came to this caption (spoiler alert): “Alison experiences an unfamiliar sensation. Could it be … happiness?”

The last scene, a full double-page drawing, finds Alison sitting on the grass at sunset outside her Vermont house, watching a bird do loops in the sky. If you look closely at the reclining figure, you can see that her mouth is unmistakably upturned. Over the decades, I’ve come to know the many moods of Bechdel’s avatar, and not all are dark. There’s also sardonic, horny, intellectually lit up. But relaxed? That brand of happiness feels new, and now ? Signs of real-world doom crop up everywhere in Spent, including in Alison’s dreams. Yet as the novel winds down, a palpable calm arrives.

Bechdel’s gift as an artist is evoking the spirit of the moment through expressions, gestures, the way two bodies lean subtly toward or away from each other. More often than not, her scenes feel too claustrophobic to linger on. But this one is a wide and soothing expanse of tamed nature, and I studied it closely for clues. Up the hill stands a barn, sturdy and welcoming, and nearby, playful goats are happily entertaining themselves. The birds are chirping (“twittertwittertwitter,” “peent!,” “twitter”). The reeds in the foreground look like they’re dancing. Alison is with her girlfriend, Holly, surrounded by friends. I felt at first confused, then seduced, and ultimately … jealous? What does Alison Bechdel know that we don’t? And how, for all these years, in a remote corner of Vermont and mostly stuck in her own head, has she figured out just what to say to the rest of us?

Bechdel began publishing her comic series Dykes to Watch Out For in the ’80s, the same decade that Alan Moore’s Watchmen and Art Spiegelman’s Maus appeared. Graphic novel was just emerging as a term (Moore dismissed it as pompous marketing-speak for “Big Expensive Comics”). The men were writing and drawing about war and murder; Bechdel wanted to focus on her friends. She has given several explanations over the years for why she landed on DTWOF, all of them personal: Comics still had something of an outsider aura that resonated with the lesbian separatist crowd she hung out with. Also, comics did not resonate with her highbrow mother, an English teacher and a talented amateur pianist. But mostly Bechdel talks about being unable to find her own quotidian queerness reflected in any artistic form, so she created one.

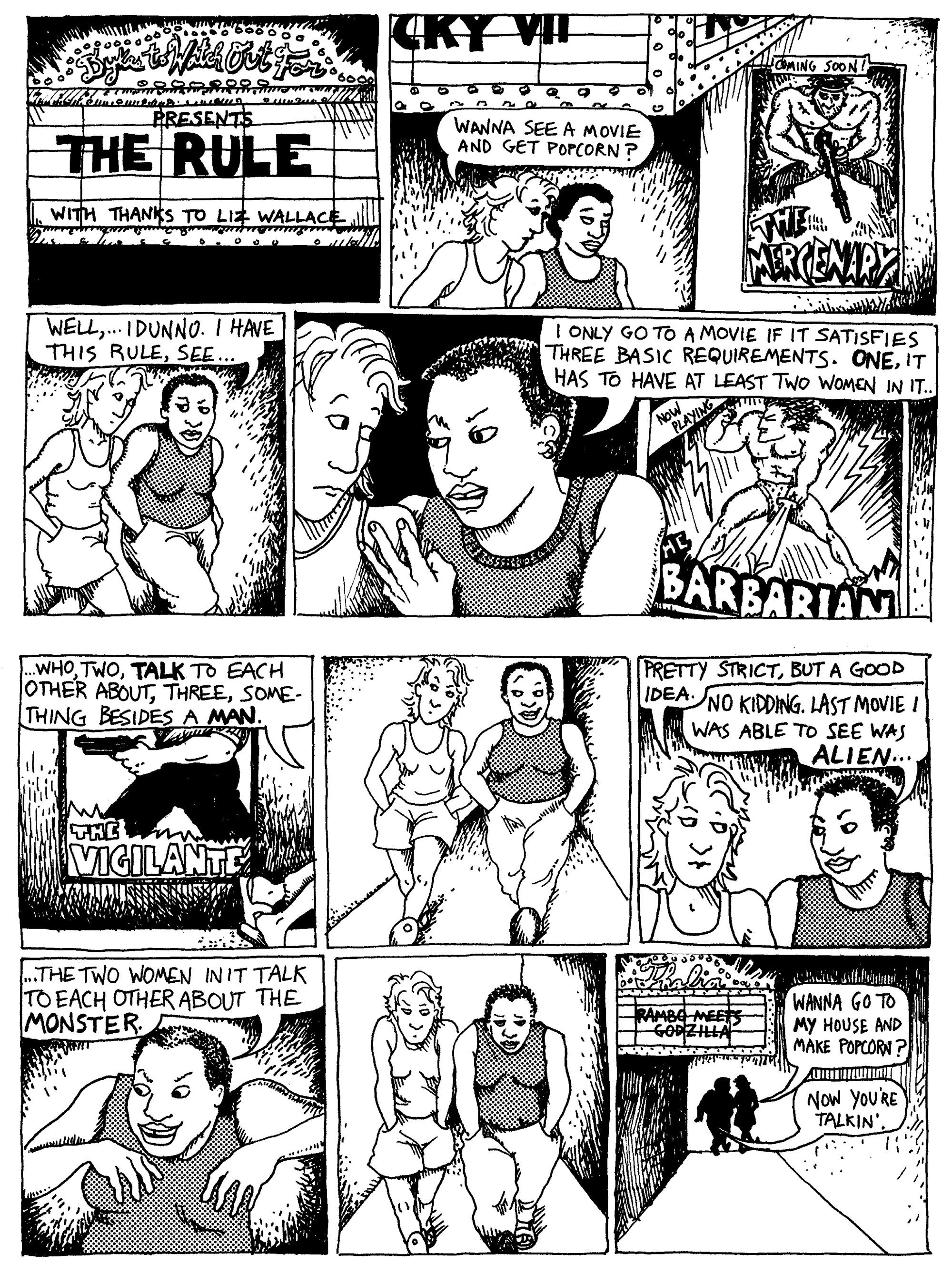

The strip, which was serialized in more than 50 alternative newspapers for 25 years, could be as soapy as Friends and Sex and the City, but with a lot fewer men and meat products, and almost no shopping. The Alison character, the neurotic hub of the collective, went by “Mo.” Coming of age in an unnamed midwestern city, she and her activist friends had sex, broke up, ate Szechuan vegetable pulp, and complained about the “Republican lynch mob.” When Mo would have panic attacks, her friends would suggest that she “cut back on the Earl Grey.” In “The Rule,” which ran in 1985 and soon inspired a cultural trope, two women discuss what movie to see, and one lists her three requirements: It has to feature at least two women who talk to each other about something other than a man. This became known as the Bechdel Test, and no matter how many times Bechdel says that the list was a joke, Reddit still loves it. (In the strip, by the way, the pair can’t find such a movie, so they go home.)

By the end of Dykes to Watch Out For’s run, in 2008, a gay character was the lead in one of the aughts’ most popular network sitcoms, and gay marriage had been legalized in two states. For decades, Bechdel had captured queer life with pitch-perfect mocking-insider’s affection, and then she made a career turn that might have seemed a cultural retreat of sorts: She decided to let Mo morph into “Alison,” the protagonist of a pair of family memoirs. But the more Bechdel turned inward, the more famous she got, and along the way, fame gave her something new to feel ambivalent, even panicked, about.

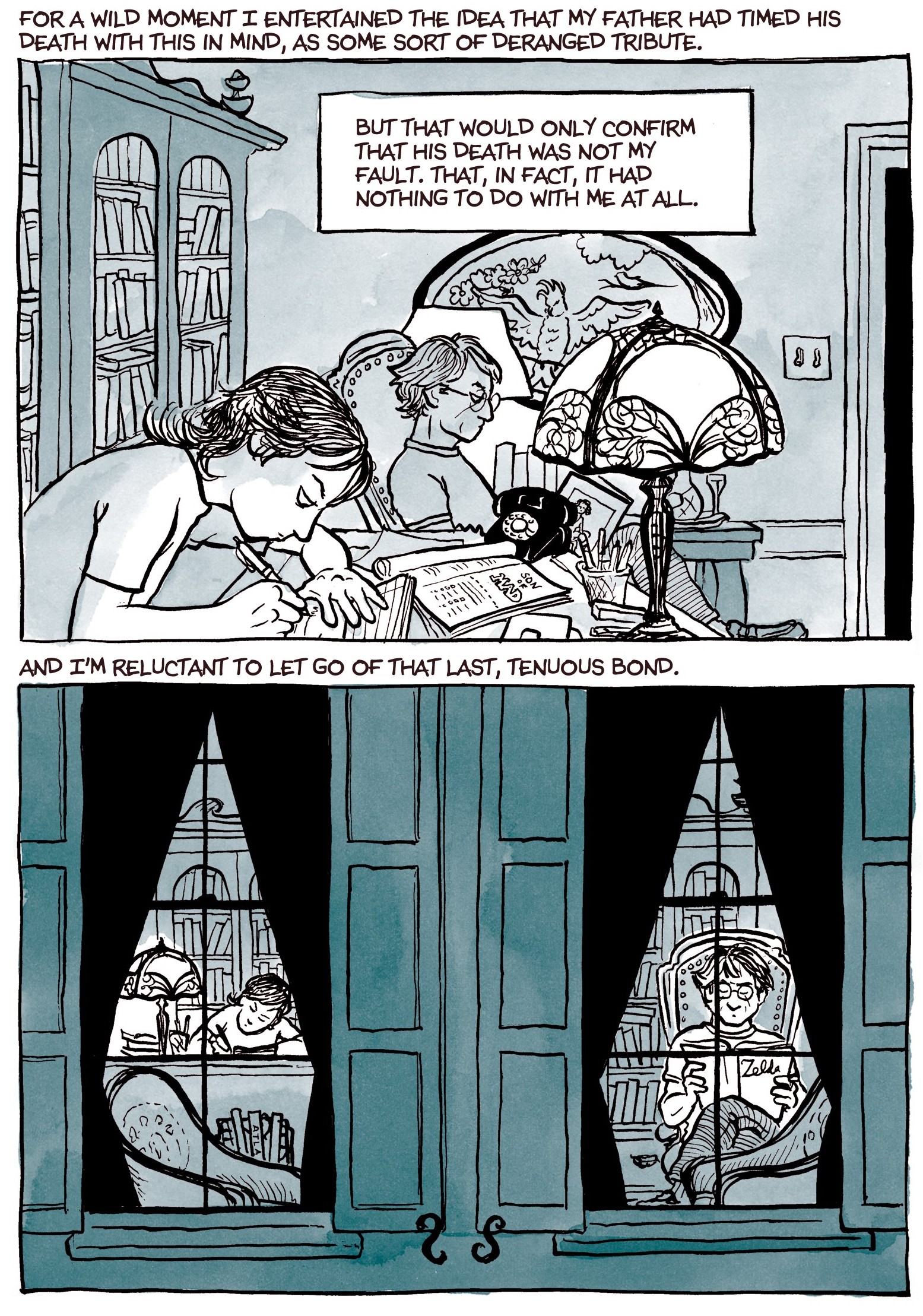

Nothing about the central, bewildering tragedy in Bechdel’s 2006 breakout, Fun Home, suggests an obvious mainstream hit: In 1980, months after 19-year-old Alison came out as a lesbian to her parents, her father, who’d been sleeping with men but hiding it, got hit by a truck—or, Bechdel intimates, put himself in the path of a truck. But Bechdel achieved the alchemy of memoir at its best, making her singular experience so specific and vivid that it became generalizable.

Although she didn’t call it that, her subject was emotional neglect. Early on, we learn that her father was “monomaniacal” in his dedication to restoring the old Gothic Revival house they lived in. If one of the children couldn’t hold up a mirror or a giant Christmas tree long enough to suit their decorator father, he might hit them. “I grew to resent the way my father treated his furniture like children, and his children like furniture,” Bechdel wrote. She portrayed a man besieged by his own demons, and then, in Are You My Mother? A Comic Drama (2012), a mother who couldn’t be bothered to pay attention. And who among us can’t relate to some version of parental dysfunction? A bit later, her sometimes-exhausting internal monologues arrived on Broadway in song form, which aired out the neurosis. The effect was to turn Fun Home into a gentler story of self-discovery.

Spent is not technically autobiographical, although I’ve come to think of it loosely as the third in a trio of memoirs: Moving beyond Bechdel’s biological family, it revolves around her chosen family, which feels genuinely more fun and more like home. The main character is, again, Alison. Her girlfriend shares the name Holly with Bechdel’s real-life partner (Holly Rae Taylor), and the setting is Vermont, where they actually live. But Holly’s job has been tweaked, and their friend circle consists of various fictional characters from DTWOF—older now, some saddled with jobs and progeny, all as libidinous as ever—who live together in a group house as part of a “longitudinal study on communal living” (invented, as far as I know, but perfectly plausible in Vermont).

While the group house cycles through comic sexual and domestic dramas, Alison is nearby nursing her most recent anxiety—her growing fame. Bechdel isn’t purely making this up: Taylor has remarked in the past that Bechdel craves fame, even as she finds that craving pathetic—and she’s astute enough to know that famous people lamenting the burdens of fame are insufferable. So in this latest version of her avatar, she’s created an Alison whose dilemma parodies contemporary celebrity culture, while also parodying herself, the author.

In the novel version, her memoir hasn’t been turned into a brilliant Broadway musical but has instead become a schlocky TV series controlled by a showrunner who loves explosions and dragons. Alison’s friends at the group house invite her over to watch episodes together (“Hollywood in da house!”), and she sits cross-armed on the couch, looking miserable. In the meantime, Holly (an artist and the owner of a composting-bin company in real life) is getting ever more famous through her viral wood-chopping videos, which both annoys Alison and makes her jealous, particularly as people in their Vermont town start to recognize Holly first. (The caption of Alison’s dream one night: “Must … generate … content …”)

To escape the pain of having her name linked to commodified junk, Alison decides to write her own television series, and lands on the idea of a reality-TV approach to showing “people how to free themselves from the grip of consumer capitalism and live a more ethical life!” Out in Hollywood, her pitch to all the major networks initially seems to be a hit, and the grip of the entertainment complex only tightens. Over at the group house, the queers continue to protest and organize, all the while still obsessing over sexual arrangements that we now call bisexual polycules.

Which one of these worlds—the capitalist vortex or the polycule-friendly group house—is more real? Life at the house seems more entertaining, but is that just a foolish fantasy designed to trick us into thinking that there is safe harbor somewhere? Or even worse, a dangerous fantasy at a time when funding a longitudinal study on communal living could get your whole university canceled? I started to wonder where Bechdel was leading us. Read too much news and you’re in the vortex. Retreat too much and you’re lost in a bubble. Or maybe that’s just black-and-white thinking, as therapists like to say. Maybe what she has learned over time, which many of us haven’t quite, is that although you can never outrun your own anxiety, you’ll never be sorry about taking a break from your own head to indulge in some friend drama next door.

Four decades ago, Bechdel stumbled into chronicling an outsider niche during the Reagan era, and she has since grown into a lesbian icon on a national stage. She weathered the AIDS crisis, has witnessed the Obergefell v. Hodges watershed and the mainstreaming of RuPaul, and now finds herself in a country where state lawmakers are trying to undo gay marriage. In Spent, she shows Alison alone at her desk trying to work on her next book, but instead obsessively Googling marauding militias, monkeypox, Musk. Meanwhile, at the group house, they take turns weighing in on the train wreck that is modern politics while playing a rollicking game of cards. “I see your abortion pill ban …” says one player, “and I raise you armed white supremacists protesting drag queen story hour in Ohio!”

Maybe if you and your friends have been worrying and talking about the patriarchal death spiral for decades, you’ve built up more stamina than the average person. You’ve probably learned by your 60s that you can’t stop the spiral, or stop fretting about it either. You have, though, discovered that solidarity can really help (even if you’re not the most sociable person)—and that you can show the rest of us that working the worry into a game of cards with old friends once in a while is more than fine.

“Where had her youthful idealism gone?” Alison asks herself at one point, a question in the air these days. Bechdel’s trajectory suggests an answer: Idealism is still simmering, especially in a rich life lived among others, and it’s still there partly because it isn’t necessarily a drop-everything call to gear up for crisis. Even as Bechdel gets more famous, and the world keeps spinning forward and backward, her real life hasn’t changed much. She has remained a semi-loner who sticks to a rigid routine in rural Vermont, which includes making morning coffee for Holly; tirelessly photographing herself in positions she intends to draw; working long hours at her desk, only sometimes productively—and watching her world.

A graphic novelist, unlike a regular novelist, has to leave room for the pictures. The neurotic inner monologue can take up only so much of the page. The cartoon Alison is situated in a space outside herself, with Holly, and goats, and neighbors. On that last, restful page of Spent, the caption reads: “And she knows that whatever happens in those coming days, she will get by with a little help from her annoying, tenderhearted, and utterly luminous friends.” Mind you, these are not Bechdel’s real friends. They are creations she’s lived with for decades. In that way, though, they are just as concrete as her actual friends, and still standing after all these years, just like the trees, the reeds, and the birds. Still standing.

* Lead image: Excerpted from the book Spent, provided courtesy of Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. © 2025 by Alison Bechdel. Reprinted by permission.

Image 1: Excerpted from the book Dykes to Watch Out For, provided courtesy of Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. © 1983 by Alison Bechdel. Reprinted by permission.

Image 2: Excerpted from the book Fun Home, provided courtesy of Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. © 2006 by Alison Bechdel. Reprinted by permission.

This article appears in the June 2025 print edition with the headline “The Secret to Happiness.”

The post Alison Bechdel’s Search for Solace appeared first on The Atlantic.