Illustrations by Dadu Shin

The Evening was small in the shadow of the other boats. When I arrived at the dock, it was well past midnight, and a misty rain was falling—the edge of a storm far out at sea. Mick, the captain, was blunt and salty; not old, but weathered. He led me on board and pointed down the ladder to the hull, where I immediately got into bed and fell asleep. When I woke up, Mick had gone into town, and I began to look around in the mute light of the overcast morning.

Our plan that October was to fish for albacore off the coast of Washington State. These would be short trips—four or five days at a time—to train me up for the summer, when I’d join Mick for a real voyage. I’d taken a Coast Guard course at a community college and had my Merchant Mariner certificate, but I’d never worked on a fishing boat before. In the daylight, the Evening looked ramshackle, as if it had survived 80 years in the northern Pacific more by luck than design. I found a few photos of Mick’s family, and the Evening’s Coast Guard certificate. “Constructed 1941, 43 feet, commercial (uninspected).” On deck, fishing lines were tangled with seaweed. Scattered everywhere were about a dozen rubber doormats stamped with the words Thankful, Grateful, and Blessed. On a workbench stood a statue of the Virgin Mary.

We spent a few days waiting for the weather to clear. Mick did paperwork and chores and I tidied the boat. One day we took the catch he had stored in the hold’s briny ice to a cannery on a spit of land between the ocean and Grays Harbor. Water from the Chehalis River flowed into the harbor, forming a standing wave where the two bodies met. I watched a ship leaving the harbor. When it crossed the river bar, it pitched and rolled. Mick and I would be taking the same route in a few days, but the Evening was half the size of that ship, old, and made of wood. The wave looked large enough to swallow us.

That afternoon, Mick suggested that we “take her out for a little spin.” Days of stormy weather had turned the water brown. Bobbing under the surface, barely visible, were entire trees that had washed down the Chehalis. Mick made sure I knew how to use the radio, and reminded me that the Coast Guard was on Channel 16. He pointed out the white canister on one wall that held the emergency radio beacon, which would go off automatically if submerged. The life raft, he explained, would release on its own.

The forecast finally showed minimal wind, minimal swell. We’d leave Thursday, October 12, 2023, and be back Sunday or Monday. On Wednesday night, I went out for a cheeseburger and called my mom. When she asked if I was excited, I said yes.

My parents thought I was throwing my life away. I was 27, and since graduating from the University of Virginia five years earlier, I’d been living in California, where I spent my time working at the counter of a surf shop, running cocktails to tourists on the ferry to Catalina Island, and surfing. In college, I’d talked about going to law school, or taking the Foreign Service exam. But as graduation approached, I began to look down the line at the rest of my life, and I knew I didn’t want that kind of career. I wasn’t sure I wanted any career at all.

I’d read East of Eden and Barbarian Days, and imagined California as a place where I could get far away from my East Coast upbringing, the collar-and-tie of my Episcopal-school childhood. I didn’t break the news to my parents until a week before my departure.

They said I hadn’t thought it through, that it didn’t sound like I had a plan. The lack of a plan was the point, I told them: “I’ll bus tables or whatever—I can find a job when I get there.” I could tell they thought the whole thing was ridiculous. In the end, I blew up at them. I told them I didn’t want the life they had chosen for me. I told them that they didn’t understand me, that I hadn’t asked for and didn’t want the blessings they’d given me.

After I left, I’d call home about once a month. They’d ask how I was doing; I’d tell them I was “figuring things out just fine.”

I bounced around—San Diego, Santa Cruz, Newport Beach—making friends and surfing as much as possible: daily, twice daily, sometimes all day long. But by the summer of 2023, I was restless. I would never have admitted it to my parents, but my job at the surf shop was getting old. Even surfing itself was beginning to feel rote—the same breaks, the same people, the same wave.

I wanted to get out of California, at least for a little while. I’d go to Australia for a year-long surfing bender. Maybe I’d meet some Australian girl—no, I definitely would—and never come back. I got a work visa. All I needed was enough money to make the trip.

Some of my friends had worked on fishing boats. One of them had spent a few seasons on a salmon boat in Alaska. He had shown me photos and told me the pay was good. In three months, I could earn enough to live on for a year. The idea of being out in deep waters appealed to me. Surf breaks are, by their nature, near shore, and even on my board, I couldn’t seem to escape the sounds of traffic on the Pacific Coast Highway. Bobbing at the ocean’s edge, waiting for waves that had started their lives as swells hundreds if not thousands of miles away, I began to wonder, What’s it like out there?

Another friend put me in touch with his old captain, a man named Michael Diamond. He introduced himself as Mick when we talked briefly over the phone. I’d do the practice runs with him in the fall to prepare for a three-month voyage over the summer. Then, Australia. He texted to confirm: “2 trips then you trained for next year.” “We can fish til they are gone and quit biting!”

We longlined for albacore that first day. We had some luck, bringing in maybe two or three dozen fish. It was hard work, but exhilarating, and the more we caught, the more I liked it. We fished until sunset, and ate rib eye for dinner. I climbed down to my bunk and fell asleep.

The second day, I woke at sunrise. The Evening was rocking from side to side, and it was harder to climb the ladder than it had been to go down it the night before. On the main deck, Mick had already gotten to work, setting up the lines on the boat’s starboard side.

The day before, we could see the horizon in all directions; now we had only a few hundred yards of visibility, and the boat pitched in the rising swells. We brought in two or three fish. By noon, Mick had called me off the deck to take cover from the wind and rain in the wheelhouse, where he lit a cigar.

The combination of the rolling boat and the smoke made my stomach turn. I needed fresh air. I went back outside. Waves were breaking over the bow, soaking my clothes, but I remained on the deck, bracing myself on the rails, for nearly an hour. When I couldn’t handle the cold anymore, I went back into the wheelhouse and found Mick resting in his berth—the rough seas had gotten to him, too. The Evening was on autopilot, on course back to the harbor.

I sat in the captain’s seat and tried to keep watch through the windshield, but I could barely see the waves before they slammed into the glass. The boat was rolling and pitching. As Mick slept, I watched our progress on the electronic chart: The boat was a small black triangle in a field of gray. We were maybe 20 miles offshore, and at our speed, it would be hours, well after sunset, before we reached the harbor. I was dizzy and nauseated and anxious, but watching our path in two simplified dimensions on-screen, I felt sure we’d make it.

But the storm kept picking up. An hour passed, then another, and we were still far from land. I half-crawled to the back of the wheelhouse and looked out the porthole. Waves began washing over the rails. A cooler was swept out to sea. There went our sandwiches. An even bigger wave pushed the stern underwater. I could feel the Evening’s center of gravity shift past the point of rebalancing. It was like leaning too far back in a chair.

I walked with one foot on the floor and the other on the wall to reach Mick. I shook him awake. “I think we need to get off now,” I told him. I reached for the radio and sent out a Mayday.

Mick opened his eyes but didn’t seem to understand. I pulled him out of bed and helped him into the seat behind the wheel. I couldn’t tell what was wrong with him. I could see seawater against the wheelhouse windows. We had to get out. I was sure Mick would follow, but when I turned around, he was frozen in the seat, gripping the armrests, looking straight through me. I shouted to him to come outside, but he didn’t move. Then I fell into the sea.

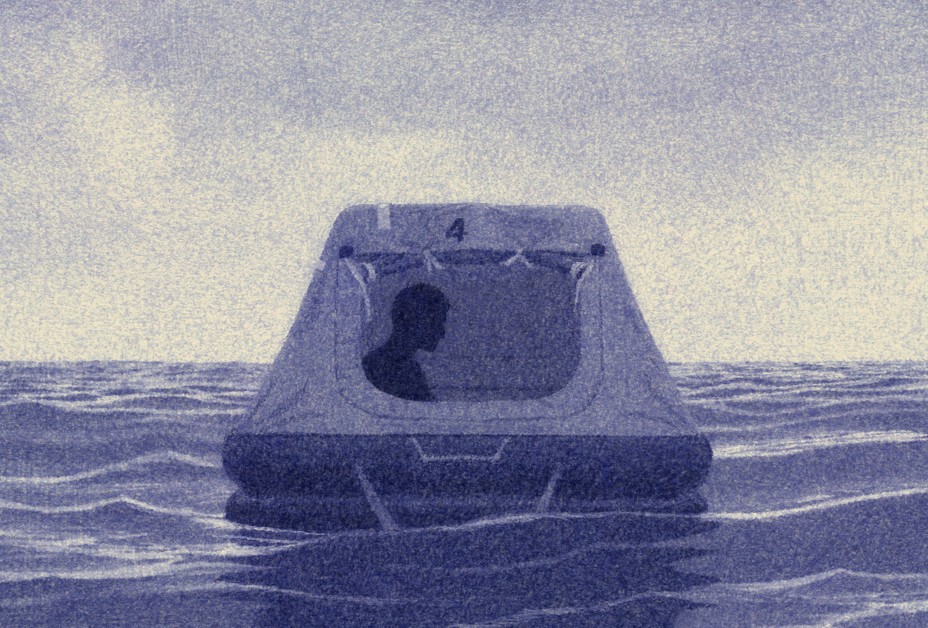

I was too shocked to feel cold. I could see the lines coming off the now-submerged masts and prayed I wouldn’t get tangled in one and be dragged down with the boat. I found the lid of the fishhold—a piece of wood insulated with foam—floating nearby and pulled myself on top of it. I was sure the Mayday had been transmitted. A helicopter would appear in no time to save us. I needed to stay afloat for half an hour, an hour at most. Then I saw the lifeboat, undeployed, floating in its canister a few feet away. I swam over and yanked the rip cord, and the raft inflated. I climbed in.

Gasping and shaking in the raft, I searched for Mick but couldn’t see him. The Evening had rolled onto its port side and was almost completely submerged. Then the bow rose suddenly upward and broke the surface. A plume of exhaust rushed out of the exposed pipe on the wheelhouse roof and the ship sank quickly. No more than five minutes had passed since I’d woken the captain.

The life raft was small but sheltered, like a kiddie pool but sturdier, and with a camping tent on top. The sides shuddered in the wind and rain, but I felt relatively safe inside. Certain that rescue was coming and exhausted by shock, I fell asleep.

When I awoke, the storm was still raging. I opened the flap for a moment, and saw the sun low in the sky. I didn’t know how much time had passed since I’d fallen asleep—maybe an hour, maybe an entire night. I needed to find some way to situate myself in this strange new reality, and began by taking inventory.

I had the clothes on my back: wool cap, flannel shirt, pants, boots, and a sweater, a Christmas gift from my grandmother. I had my phone (destroyed) and my wallet. On the raft, I found a collapsible oar, a first-aid kit, a small fishing kit, two emergency blankets, and an assortment of signals: four hand flares, three rocket flares, and three cans of orange smoke. I had food—a box of maybe a dozen emergency rations, which looked like beige bars of soap and tasted like oily shortbread—and two liters’ worth of drinking water, in individual packages.

The oar was useless in the rough seas, and I had no clue which way to row. I immediately wasted two flares, firing them into the air in the deluded hope that an approaching rescuer would see them. In the fishing kit was a razor blade, intended for filleting a hooked fish, though it seemed to invite another use. I thought of throwing it overboard, but instead stashed it away.

I tried not to worry. Getting a helicopter airborne probably took a little time, especially in a storm. Worst case—if our Mayday hadn’t been heard—someone would figure out we were missing and come looking. We were supposed to be gone for only four or five days, and if we didn’t return as planned, someone would notice—the harbormaster, or another captain, or our families. We’d left on Thursday and the ship had gone down on Friday. At the very latest, I figured I’d be rescued by Monday or Tuesday. I didn’t worry, at first, about my food or water running out. I just had to wait.

I thought a lot about Mick, wondering if I could have done more to save him, wondering why he’d been catatonic as the boat sank. I hadn’t seen any alcohol or drugs on the boat. Had he been seasick? Paralyzed by fear? Either way, I felt furious with him, and then guilty for my fury.

My first three or four days on the raft, the sky was so dark with storm clouds that I could barely see the sun move from east to west. With nothing to mark the hours, each day felt like it contained far more than 24. I remembered reading about Franciscan monks and how they ordered their days around work and prayer, and I decided I needed to devise my own routine, starting with a regular lookout.

Every morning, and then periodically throughout the day, I unzipped the flap that kept the wind and water out of the raft and checked to see if anything was out there—land, or a boat, or a plane. I bailed out water and wiped off the condensation that had accumulated inside the raft from my breath. I removed my clothes, one piece at a time, and hung them up on an interior bar of the shelter to dry, though they never fully did. I added new tasks when the need arose, such as blowing into a valve to reinflate the raft when it began to sag, and organizing and reorganizing my water, food, and flares.

Tossed by the waves, I could never sleep more than an hour or two at a time. I hadn’t been dry, not completely, since I’d fallen into the ocean. Soon the emergency blankets were worn to shreds. The silver foil deteriorated, exposing a sharp plastic mesh that cut into my waterlogged fingers. I tossed the scraps overboard, and from then on, I used the dry bag—a small rubber rucksack—as a blanket. It was hardly bigger than a pillowcase, but by ripping one of its seams and pulling my knees tight against my chest and my arms against my sides, I was able to cover myself nearly up to my collarbone. Desperate for any bit of warmth, I ignored the cramping discomfort it caused.

I prayed often, always aloud. At first, pleas for rescue. Over and over, I asked God to save me—not my soul, but my physical self. After days of praying the same prayer, I tried offering God something in return. First, I apologized for every past transgression I could remember. Any injustice or sin I feared I may have committed, I tried to atone for, so God would listen to my prayers. I used what I could recall of the Ten Commandments to accuse myself. I hadn’t honored the Sabbath in years; I had lied; I had coveted; I had stolen. Worst of all, I hadn’t honored my mother and father. I asked God to forgive me for the way I had treated my parents.

The life I’d chosen had put me in this situation. All the self-assurance I’d had that I could figure everything out on my own had led me here, and now I was going to lose my life and my parents were going to lose their son. Their doubts about my decision rose up in my mind and became my own doubts. I saw that my mom and dad had tried to discourage me not because they wanted to control me, but because they loved me. I wished I could tell them that I understood them now. I told God that I was sorry, for everything, and that if he gave me the chance, I’d do my best to make everything right.

I saw my first ship after five or maybe six days of drifting. I launched a flare into the sky. The ship was so close, I had no doubt the crew would spot me. I could see the containers it was carrying; the company’s name, Hapag-Lloyd, was painted on the side. As the rocket arced through the air, I imagined being lifted up out of the ocean. Someone would give me dry clothes and a hot meal, and they’d let me call my mom and dad on a satellite phone. I’d tell my parents what had happened and that I was all right. Then the ship would drop me off at its next port of call, and I’d fly back to California, and my life would return to normal—a happy, beautiful normal. I’d sit in traffic on the 55 with a smile on my face.

But as the flare rose, and fell, and was extinguished in the ocean, the ship kept going. Soon it disappeared over the horizon.

I’d been rationing my water, never consuming more than the equivalent of a small glass every 24 hours. But by the end of my first week on the raft, I knew that my distress signal would never be answered, that the emergency positioning beacon had failed to transmit. I was alone, and I was terribly, terribly thirsty.

What sense was there in suffering if all it meant was postponing the inevitable? I drank as much as I could stomach and closed my eyes. The next morning, I saw that no water was left.

I had strange, vivid dreams. Then I didn’t dream at all so much as hallucinate. As my eyes would begin to close, I’d hear splashing, like the breaching of a school of big fish, and then suddenly I’d feel that the raft was being propelled forward, as if on a towline, over the surface of the water. But every morning, I always seemed to be in the same place, at the center of the jumbled swells—rising, falling, sometimes breaking.

One night I dreamed that the life raft had washed ashore, on the bank of a pond. I stepped into the reeds, and then onto a road that led me to a small house. My friend Jack was sitting on the porch. He waved; he had been expecting me. But I was embarrassed—my clothes were wet and dirty, my hair tangled, my face covered with a patchy beard. I made an excuse. I told him my car had broken down and I was on my way into town to get a screwdriver. I’d be a little late for our appointment. “Don’t worry, take your time,” Jack told me. “Take all the time you need.” I walked back to the pond, climbed onto the life raft, and fell asleep. When I woke up for real, I opened the flap and found myself once again—still—in the middle of the ocean.

Even when I was awake, I had experiences that I couldn’t explain. One day, I sensed that I wasn’t alone in the life raft. I couldn’t see a figure or hear a voice, but I knew they were there, and I knew their name. It was the I.O.B. I said it to myself: “Eye-Oh-Bee.”

Was I losing my mind? I laughed at myself. Only a sane person would be able to laugh at himself, right? But I couldn’t shake the thought of the I.O.B. And I didn’t want to.

The I.O.B. brought me a sense of peace I hadn’t ever felt on the life raft. It wasn’t great company—it was silent and invisible, after all—but for the first time I felt like something, someone, was there to witness my continued existence, my choice to stay alive. I had often thought that if I died, and my body was never recovered, no one would ever know how desperately I had clung to life, how I’d fought to live even when despair felt absolute and overpowering. My parents wouldn’t know; my friends wouldn’t know. But the I.O.B. knew.

Not long after the I.O.B. appeared, I decided to open the flap, just a little, to see if anything was visible. In the eddy was a sunfish—a large, flat, primordial-looking bony fish—just a few feet from me. Its long, narrow dorsal fin broke the surface, oscillating gently, as if it were waving. I waved back.

By now I had lost track of time completely. The sea grew calm. One night, before the last of the clouds cleared, I was able to collect some rainwater to drink. It tasted cold and sweet. I even managed to catch a small fish. I bled it with the razor blade, and ate it to the bone. I threw the line back in the water, but didn’t catch another. Sometimes I could see land on the horizon, and I tried to row toward it, counting my strokes, into the hundreds, the thousands, but I never made it any closer.

I’d seen maybe five or six ships by then, most so far off that they’d looked like two-dimensional paper cutouts pasted on the horizon. I wasted my last rocket on them, and lit the hand flares, and popped canisters of thick orange smoke. For days I prayed that God would send more ships, but each time one passed and didn’t stop, I was left so bereft, so gutted by the brush with hope, that I began to feel that I would rather never see another. Now I had only one flare left. Holding on to it felt like holding on to life itself.

With the clearing of the storm, the temperature had dropped. During the day, the sun hitting the side of the raft was enough to keep me warm, but when night came, the cold set into my damp clothes and skin, and I shivered so violently, I couldn’t sleep. I was out of food, out of water. I knew I would not survive much longer. But even as my hope for rescue began to evaporate, so did my despair.

I was going to die. I didn’t look forward to it. I wanted to see my mom and dad again, my brother and sister, my friends. There was so much I still wanted to do. I fantasized about the smallest, most mundane things—waking up in bed, getting in my car, waiting at a red light, grabbing coffee, working. I wanted to do it all again, every day, forever and ever. But the idea of getting off the raft was becoming a distant hope, like winning the lottery—it would be really nice if it happened, but I didn’t expect it to, and I wasn’t going to tear myself up about it.

A peace I hadn’t known to look for found me. Where before I’d dreaded sunsets—the precursors to cold nights and strange dreams, and the mark of yet another day lost to the raft—now they were only sunsets, and sometimes I found them beautiful.

Yet another freezing, trembling night. At last the sun rose. Its light hit the side of the life raft, and I could feel it warming up, as if someone had lit a woodstove in the corner. Maybe now I could finally get some sleep. I pulled my hat down over my eyes and tried to let myself doze off, but I couldn’t—I couldn’t neglect my morning ritual, the first duties of my watch. I compromised with myself: I would do the morning lookout, and then get to sleep.

When I crawled across the raft and opened the flap, I saw it immediately—a boat, close enough that it actually looked real, and coming closer. I turned to get the flare, which I’d wedged into a corner. I hesitated. This was my last one.

Before I lit it, I began to scream at the very top of my lungs. I screamed until I felt as if my lungs were imploding, and kept going. When the boat was as close as it was going to get, I finally lit the flare.

The flame burned to the base, and when it reached my hand, I dropped the flare in the water, where the hot, burning metals cooled and groaned. I kept screaming, waving my hands over my head. I looked and sounded like a madman. When at last I ran out of breath, I fell silent. And in the silence, I heard someone answer me.

“We see you, we’re coming, we see you.”

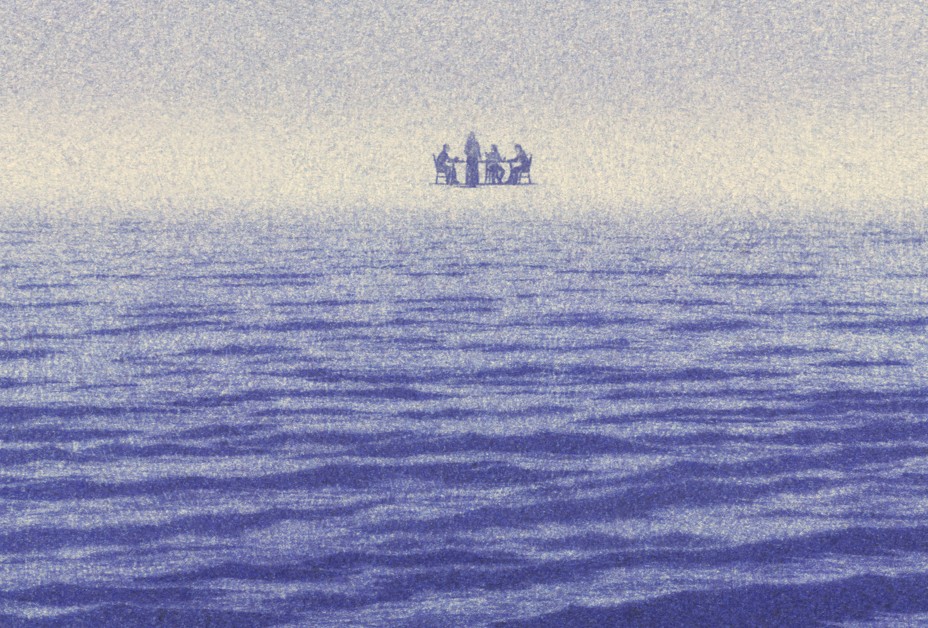

I watched the boat change its course toward me, and the crew lowered a ladder and helped me aboard. The captain cooked me warm food, and a deckhand gave me dry clothes. I ate, and cried, and thanked them. It turned out that I’d drifted far from the harbor. The land I’d seen over the horizon was Vancouver Island, some 150 miles away from where the voyage had begun. The captain said he’d seen life rafts on the ocean before, but they’d always been empty. He asked me how long I’d been in the raft. I asked him for the date.

It had been 13 days.

The Canadian Coast Guard brought me ashore at Tofino, where I was taken to the hospital. Doctors worried that, after days of dehydration and deprivation, my kidneys or heart might fail. They took some blood, ran some tests, and, miraculously, I was fine. I could go home. A nurse brought me fresh clothes and led me to a shower. When I stripped out of my hospital gown, I was shocked by how thin I was—it was as if I could see all the bones and veins beneath my skin.

Two Mounties came to the hospital to take me to the border, and I walked across, back into the United States. Officials kept me there for a few hours, asking questions about the accident. At last they let me go, and a border agent helped me onto a bus to Seattle, where I caught a plane to Baltimore. My parents picked me up. A Welcome Home banner was hanging from the cherry tree in the front yard.

It was nearly November—a month of many birthdays for my family, including my own—and, with Thanksgiving right around the corner, I decided to stay awhile. My brother and sister came home from New York, and for a couple of weeks, the house was full. It was like we were observing a strange holiday that none of us knew how to celebrate. We negotiated the awkwardness by trying to act normal, but of course nothing felt normal. A few days earlier, I had thought I would never walk the dogs with my dad again, or sit in the kitchen drinking coffee with my mom, but there I was doing just that. I wanted to tell everyone how blessed I felt, but whatever words I considered felt far too small. I suspect they felt the same.

A few days after Thanksgiving, I left for California. When I was at the airport, waiting for my flight, I unfolded from my wallet a poem that my dad had written for me. My dad will be the first to say he isn’t much of a poet, and the poem relied heavily on an old Irish toast, but the last words, I’m certain, were his own: “Now carry on.”

Mick’s body was never recovered. In the spring, I drove to San Diego for his memorial. His son told a story about a trip they’d once taken to Hawaii. He and his friend were surfing while Mick fished, waist-deep in the water. A large set rolled in, knocking Mick off his feet. When his son found him washed up on the beach, he was soaked, but he was still holding on to his cigar, and it was still, somehow, lit.

When the memorial was over, Mick’s daughter gave me a hug, and told me she was happy I had come. But I felt guilty—that it was wrong that I was there when their dad was gone.

I’m grateful that I survived, but I don’t know why I did, or what it means. I still have no idea what I want to do with my life. When you’re lost at sea, certain you’re going to die in a life raft, you ask, Why me? and receive no answer. When you’re rescued and restored to life, you ask, Why me? and still there is no answer.

This article appears in the June 2025 print edition with the headline “Lost at Sea.” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

The post Lost at Sea appeared first on The Atlantic.