Photographs by Sarah Blesener

The Toyota pickup hit the tree that May morning with enough explosive force to leave a gash that is still visible on its trunk 39 years later. Inside the truck, the bodies of three teenage boys hurled forward, each with terrible velocity.

One boy died instantly; a second was found alive outside the car. The third boy, Ian Berg, remained pinned in the driver’s seat, a bruise blooming on the right side of his forehead. He had smacked it hard—much harder than one might have guessed from the bruise alone—which caused the soft mass of his brain to slam against the rigid confines of his skull. Where brain met bone, brain gave way. The matter of his mind stretched and twisted, tore and burst.

When the jaws of life freed him from the wreckage, Ian was still alive, but unconscious. “Please don’t die. Please don’t die. Please don’t die,” his mother, Eve Baer, pleaded over him at the hospital. She imagined throwing a golden lasso around his foot to keep him from floating away.

And Ian didn’t die. After 17 days in a coma, he finally opened his eyes, but they flicked wildly around the room, unable to sync or track. He could not speak. He could not control his limbs. The severe brain injury he’d suffered, doctors said, had put him in a vegetative state. He was alive, but assumed to be cognitively gone—devoid of thought, of feeling, of consciousness.

Eve hated that term, vegetative—an “unhuman-type classification,” she thought. If you had asked her then, in 1986, she would have said she expected her 17-year-old son to fully recover. Ian had been handsome, popular, in love with a new girlfriend—the kind of golden boy upon whom fortune smiles. At school, he was known as the kid who greeted everyone, teachers included, with a hug. He and his two friends in the car belonged to a tight-knit group of seniors. But on the day he would have graduated that June, Ian was still lying in a hospital bed, his big achievement being that he’d finally made a bowel movement.

“What kind of life is that?” Ian’s brother Geoff remembers thinking. When he first arrived at the hospital, he had looked around the room for a plug to pull. The two brothers had talked about scenarios like this before, Geoff told me: “If anything ever happens to me and I can’t wipe my ass, make sure you kill me.” Angry that their mother was keeping his brother alive, Geoff fled, moving for a time to St. Thomas.

Three months after the accident, when doctors at the hospital could do no more for Ian, Eve took him home. She was adamant that he live with family, rather than under the impersonal care of a nursing home. That she had ample space for Ian and all of his specialized equipment was fortuitous. A few weeks before the accident, Eve’s husband, Marshall, had stumbled upon the Rainbow Lodge, an old hotel for hunters and fishers, for sale near Woodstock, New York. He loved the idea of a compound for their big blended family—his two grown children plus nieces and nephews, as well as Eve’s four kids, of whom Ian is the youngest. The sale was finalized while Ian was in the hospital.

At the lodge, Eve and a rotating cast of caretakers kept Ian alive: bathing him, pureeing home-cooked meals for his feeding tube, changing the urine bag that drained his catheter. She also devised a busy schedule of therapies, anchored by up to six hours a day of psychomotor “patterning”—an exercise program she’d read about in which a team of volunteers took each of Ian’s limbs and moved them in a pattern that mimicked an infant learning to crawl. Friends and acquaintances came to help with patterning; some started living in the lodge’s guest rooms, staying for months or even years. They formed a kind of unconventional extended family, with Ian at the center. Every Sunday, Eve cooked big dinners for the crowd.

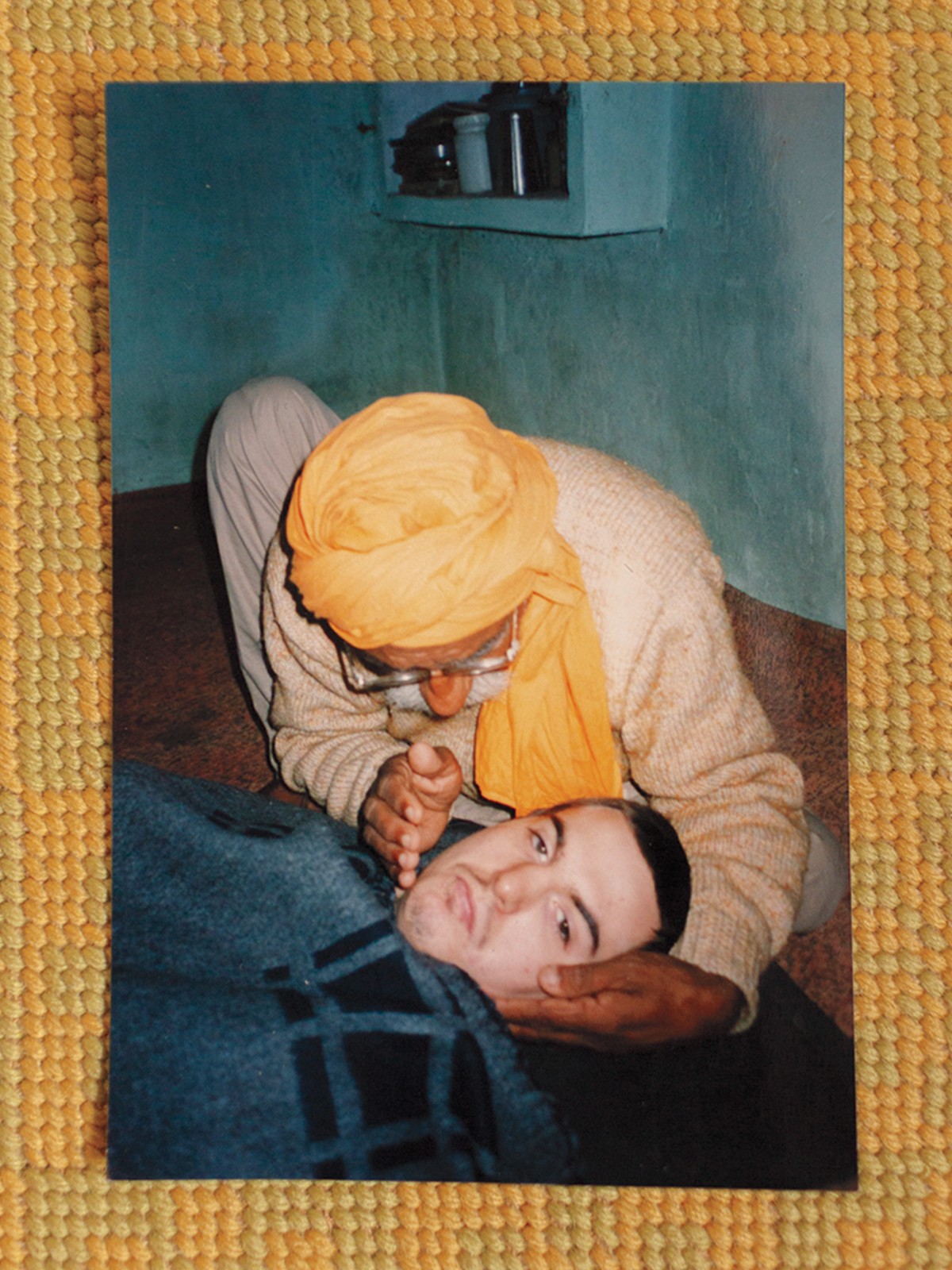

The patterning exercises, which are not based on science, ultimately did not really help Ian. But his mother didn’t dwell on this. She made regular calls to the National Institutes of Health to inquire about the latest brain-injury research. And where mainstream medicine failed, Eve—who had moved to Woodstock in the ’60s as a “wannabe bohemian slash beatnik”—turned enthusiastically to alternatives. Ian was treated by the spiritual guru Ram Dass; a “magic man” with a pendulum; a craniosacral therapist; a Buddhist monk; Filipino “psychic surgeons”; and a healer in Chandigarh, India. Eve and Marshall took him on the 7,000-mile journey to India themselves, pushing him in a rented collapsible wheelchair. When, after all of this, Ian’s condition still did not improve, Eve became angry. It was one of the rare times that she allowed disappointment to puncture her relentless optimism.

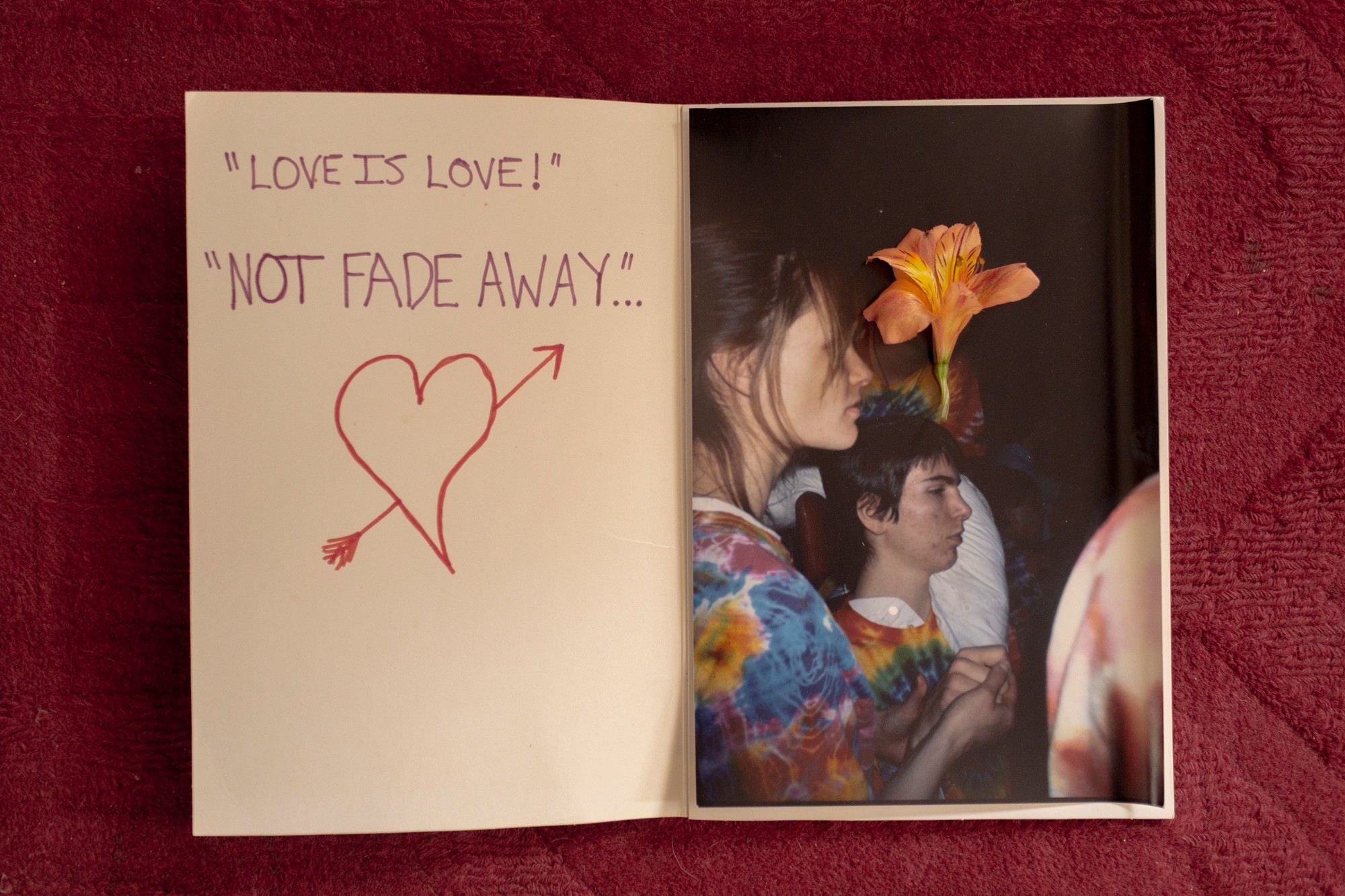

Still, like so many other family members of vegetative patients, she held on to a mother’s belief that Ian could understand everything around him. She took care, when shaving him, to leave the wispy mustache he had been trying to grow. When his high-school friends went to see the Grateful Dead, she brought him along in his wheelchair and a tie-dyed shirt. She kept believing for herself as much as for Ian: If her son was aware, it would mean her gestures of love were not unseen, her words not unheard.

Science would take decades to catch up with Eve, but she turned out to be right in one crucial respect: Ian is still aware. Doctors now agree that he can see, he can hear, and he can understand, at least in some ways, the people around him.

Over the past 20 years, the science of consciousness has undergone a reckoning as researchers have used new tools to peer inside the brains of people once thought to lack any cognitive function. Ian is part of a landmark study published in The New England Journal of Medicine last year, which found that 25 percent of unresponsive brain-injury patients show signs of awareness, based on their brain activity. The finding suggests that there could be tens of thousands of people like Ian in the United States—many in nursing homes where caretakers might have no clue that their patients silently understand and think and feel. These patients live in a profound isolation, their conscious minds trapped inside unresponsive bodies. Doctors are just beginning to grasp what it might take to help them.

For Ian, the signs were there, if not right at the beginning, at least early on. Three years after the accident, he began to laugh.

Eve was in the kitchen with him, idly singing the Jeopardy theme song in a silly falsetto when she heard it: “Ha!” Laughter? Laughter! “Other than a cough, it was the first sound I heard from him in three years,” she told me. In time, Ian started laughing at other things too: stories Eve made up about a cantankerous Russian named Boris, the word debris, pots clanging, keys jangling. Fart and poop jokes were a perennial favorite; his brain seemed to have preserved a 17-year-old’s sense of humor. His friends and family took that to mean the Ian they knew was still in there. What else might he be thinking?

At the time, Ian was not regularly seeing a neurologist. But even if he had been, most neurologists in the ’80s would not have known what to make of his laughter; it flew in the face of conventional wisdom.

Doctors first defined the condition of the persistent vegetative state in 1972, less than a decade and a half before Ian’s accident. Fred Plum and Bryan Jennett coined the term to describe a perplexing new class of patients—people who, thanks to advances in medical care, were surviving brain injuries that used to be fatal, but were still left stranded somewhere short of consciousness. This condition is distinct from coma, a temporary state in which the eyes are closed. Vegetative patients are awake; their eyes are open, and they may be neither silent nor still. They can moan and move their limbs, just without purpose or control. And while their bodies continue to breathe, sleep, wake, and digest, they seem to have no connection to the outside world. Today, experts sometimes refer to the vegetative state as “unresponsive wakefulness syndrome.”

Back then, the two doctors also distinguished it from locked-in syndrome, which Plum had helped name a few years prior. Locked-in patients are fully conscious though immobile, except for typically their eyes. (Jean-Dominique Bauby wrote his famous 1997 memoir about locked-in syndrome, The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, by blinking out one letter at a time.) In contrast, Plum and Jennett considered the vegetative state “mindless,” with no cognitive function intact.

What, then, could the laughter mean? By the ’90s, some of the most prominent experts on consciousness—including Plum and Jennett themselves—had begun to realize that they had perhaps too categorically or hastily dismissed patients diagnosed as vegetative. Researchers were documenting flickers of potential consciousness in some supposedly vegetative patients. These patients could utter occasional words, grasp for an object every now and then, or seem to answer the odd question with a gesture—suggesting that they were at least sometimes aware of their surroundings. They seemed to be neither vegetative nor fully conscious, but fluctuating on a continuum.

This in-between space became formally recognized in 2002 as the “minimally conscious state,” in an effort led by Joseph Giacino, a neuropsychologist who specializes in rehabilitation after brain injury. (Coma, vegetative, and minimally conscious are sometimes collectively called “disorders of consciousness.”)

One day in spring 2007, Marshall, Ian’s stepfather, slipped on a mossy stone and fractured his hip. As he and Eve waited for an ambulance, the phone rang. Giacino had heard about Eve’s NIH inquiries, and he was interested in meeting Ian—he wondered if the minimally conscious diagnosis might apply to him. If so, Ian could qualify for a new experimental trial.

Giacino didn’t make any promises. Still, after all those years, Eve told me, “he was the first voice of positive possibility that I heard.” So even as Marshall lay next to her with his broken hip, neither of them dared hang up the phone.

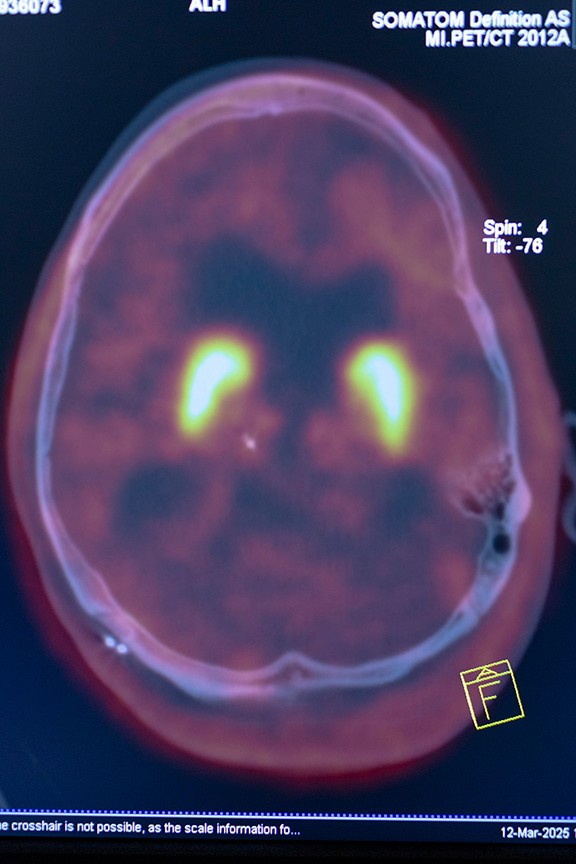

Around this time, in 2006, an astonishing case report came out from researchers led by Adrian Owen, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Cambridge; it suggested that even vegetative patients could retain some awareness. Owen found a 23-year-old woman who had been in a car accident. Months later, she still had no response on behavioral exams. But in an fMRI machine, her brain looked surprisingly active: When she was asked to imagine playing tennis, blood flowed to her brain’s supplementary motor area, a region that helps coordinate movement. When she was asked to imagine visiting the rooms of her house, blood flowed to different parts of her brain, including the parahippocampal gyrus, a strip of cortex crucial for spatial navigation. And when she was told to rest, these patterns of brain activity ceased. Based on the limited window of an fMRI scan, at least, she seemed to understand everything she was being asked to do.

“Unsettling and disturbing” is how one neurologist described the implications of the study to me. Also: controversial. Another doctor recounted a scientific meeting soon after where the speakers were split 50–50 on whether to accept the results. Was the fMRI finding just a fluke? Owen did not inform the woman’s family of what he found, because the study’s ethical protocol was ambiguous about how much information he could share. He wishes he could have. The woman died in 2011, without her family ever being told that she might have been aware.

Over time, Owen and his group identified more patients with what they came to call “covert awareness.” Some were vegetative, while others were considered minimally conscious, based on behaviors such as eye tracking and command following. The researchers found that outward response and inner awareness were not always correlated: The most physically responsive patients were not necessarily the ones with the clearest signs of brain activity when asked to imagine the tasks. Covert awareness, then, can be detected only using tools that peer at a brain’s inner workings, such as fMRI.

In 2010, one of Owen’s collaborators, the Belgian neurologist Steven Laureys, asked a minimally conscious patient, a 22-year-old man, a series of five yes-or-no questions while he was in an fMRI machine, covering topics such as his father’s name and the last vacation he took prior to his motorcycle accident. To answer yes, the patient would imagine playing tennis for 30 seconds; to answer no, he would imagine walking through his house. The researchers ran through the questions only once, but he got them all right, the appropriate region of his brain lighting up each time.

It is hard to say what experience of human consciousness some colored pixels on a brain scan really depict. To answer intentionally, the patient would have had to understand language. He would also have needed to store the questions in his working memory and retrieve the answers from his long-term memory. In my conversations with neurologists, this was the study they cited again and again as the most compelling evidence of covert awareness.

A few years later, using the same yes-or-no method, Owen found a vegetative patient who seemed to know about his niece, born after his brain injury. To Owen, this suggested that the man was laying down new memories, that life was not simply passing him by. In yet another case, Owen used fMRI not just to quiz a 38-year-old vegetative man, but to actually ask about the quality of his life 12 years post-injury: Was he in pain right now? No. Did he still enjoy watching hockey on TV, as he had before his accident? Yes.

Most researchers I spoke with were reluctant to speculate about the inner life of these brain-injury patients, because the answer lies beyond any known science. The brains of minimally conscious patients do activate in response to pain or music, Laureys told me, but their experience of pain or music is likely different from yours or mine. Their state of consciousness may resemble the twilight zone of drifting in and out of sleep; it almost certainly differs from person to person. Owen believes that some of his vegetative patients may actually be “completely conscious,” akin to a locked-in person who is fully aware, but cannot move even their eyes. Until that is proved otherwise, he sees no reason not to extend them the benefit of the doubt.

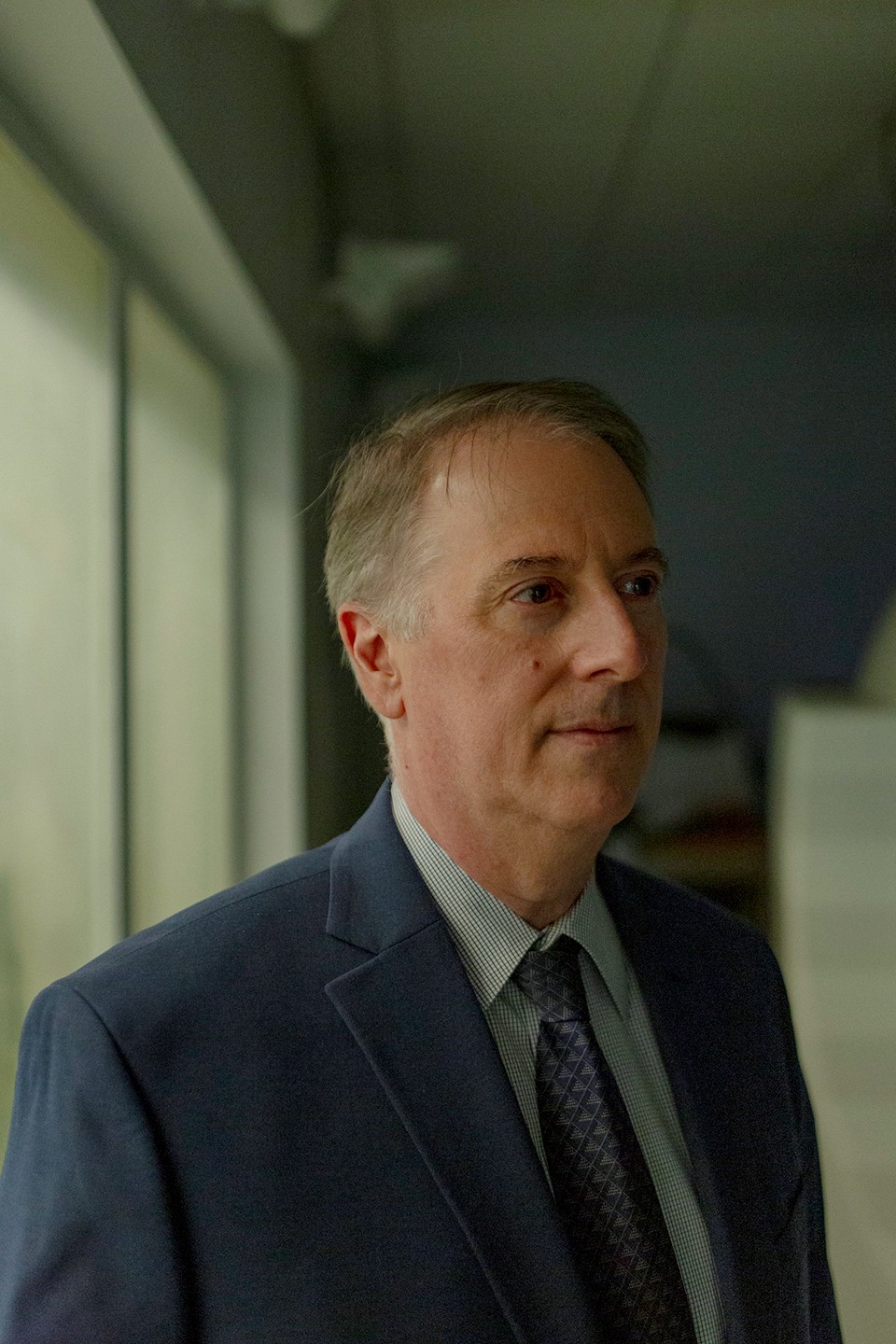

Several months after the phone call from Giacino’s office, Ian’s family made the trip to New Jersey to meet the researcher. In the exam room, Giacino put Ian through an intense battery of tests. He found that Ian could intermittently reach on command for a red ball. He laughed at loud noises, such as keys jangling, which Giacino said could be a simple response to the sound. But Ian also laughed appropriately at jokes, especially adolescent ones, as if he understood humor and intent. These behaviors were enough to qualify Ian for a brand-new diagnosis two decades after his accident: not vegetative, but minimally conscious.

Giacino’s collaborators were eager to put Ian in an fMRI machine, to see what might be happening inside his brain. On a separate trip, this time to an fMRI facility in New York City, his family met Nicholas Schiff, a neurologist at Weill Cornell and a protégé of Fred Plum’s. Schiff, too, was intrigued by Ian’s laughter, and the possibility that he understood more than he could physically let on. Schiff’s team showed Ian pictures and played voices—to see whether his brain could process faces and speech—and asked him to imagine tasks such as walking around his house.

Ian’s brother Geoff was also at this scan, having by then returned to New York. Crammed into the small fMRI control room with all the scientists peering at Ian’s brain, he remembers being incredulous at the things they wanted his brother to imagine. “You really think he can understand you?” he asked.

The scientists did. They believed Ian still retained some kind of consciousness. They also thought there was a chance, with luck and the right tools, of unlocking more. This had happened before. In some extraordinary patients, the line between conscious and unconscious is more permeable than one might expect.

In 2003, Terry Wallis, in Arkansas, suddenly uttered “Mom!” after 19 years as a vegetative patient in a nursing home. Then he said “Pepsi”—his favorite soft drink. After that, his mother took him home. Wallis couldn’t move below his neck and he struggled with his memory and impulse control, but he began to speak in short sentences, recognized his family, and continued to request Pepsis. In retrospect, he probably had not been vegetative at all, but minimally conscious during those first 19 years. His mom had seen signs that others at the nursing home had not: Wallis occasionally tracked objects with his eyes, and he became agitated after witnessing the death of his roommate with dementia.

Slowly, over time, Wallis’s brain had recovered to the point of regaining speech. When Schiff and his colleagues later scanned him, they found changes that suggested neuronal connections were being formed and pruned decades after his injury. “Terry changed what we thought about what might be possible,” Schiff told Ian’s family.

There was also Louis Viljoen, in South Africa, who in 1999 began speaking when put on zolpidem, better known as Ambien, a sedative that was, ironically, supposed to put him to sleep. He, too, had been declared vegetative—a “cabbage,” according to one doctor—after being hit by a truck. Within 25 minutes of taking zolpidem, his mother recalled, he started making his first sounds, and when she spoke, he responded, “Hello, Mummy.” Then the effects of the drug faded as rapidly as they’d come on.

Viljoen would continue taking zolpidem every day; he eventually recovered enough to be conscious even without the drug, but a daily dose reanimated him further. “After nine minutes the grey pallor disappears and his face flushes. He starts smiling and laughing. After 10 minutes he begins asking questions,” a reporter who met him in 2006 wrote. Several other drugs, including amantadine and apomorphine, can have similarly arousing effects, though none has worked in more than a tiny sliver of patients. In certain people, for reasons still not understood, they might activate a damaged brain just enough to kick it into gear, “like catching a ride on a wave,” Schiff, who has studied patients on Ambien, told me.

Greg Pearson, in New Jersey, had electrodes implanted in his thalamus in 2005 as part of a study by Schiff and Giacino. The thalamus is a walnut-size region of the brain that sits above the opening at the bottom of the skull, where the spinal cord meets the brain, a position that makes it particularly vulnerable during injury: When a bruised brain swells, it has nowhere to go but down, putting tremendous pressure on the thalamus. Because the thalamus usually regulates arousal—Schiff likens it to a pacemaker for the brain—damage to this region can induce disorders of consciousness. Schiff wondered if stimulating the thalamus could restore some of its function. And indeed, when the electrodes were turned on during surgery, Pearson blurted out his first word in many years: “Yup.” He was eventually able to recite the first 16 words of the Pledge of Allegiance and tell his mother, “I love you.”

A damaged brain, in some cases, might be more like a flickering lamp with faulty wiring than a lamp that has had its wiring ripped out. If so, that circuitry can be manipulated. The neurosurgeon Wilder Penfield realized this decades ago, when he discovered that he could make a conscious patient fall unconscious by gently pressing on a certain area of the brain.

That our consciousness might actually be dynamic, that it can be dialed up and down, is not so strange if you consider what happens every day. We become unconscious when we sleep at night, only to reanimate the next day. Could this dialing back up be artificially controlled when the brain is too damaged to do so itself?

After the publication of the study on Pearson, in 2007, Schiff couldn’t keep up with all the calls to his office. He and his colleagues were now looking for more patients, including people who were even less responsive initially than Pearson—people whose condition would test the extent of what deep-brain stimulation using electrodes could do.

Given his limited but still discernible responses, Ian seemed like the perfect candidate. The researchers were careful not to make guarantees. But Eve harbored hope that Ian could one day tell her, “I love you.” His family agreed to join the trial.

I’ll cut to the chase: Ian’s deep-brain stimulation did not work. At one point during the surgery to implant the electrodes, he said the only intelligible word he’s uttered since 1986—“Down,” in response to being asked, “What is the opposite of up?” Then he lapsed into silence once again. In the months that followed, therapists spent hours and hours asking Ian to move his arm or respond to questions, to no avail.

Geoff, who worked in video production at the time, captured the process on film. He had intended to make a documentary about what he hoped would be his brother’s recovery. In addition to filming Ian in the trial, he’d taped interviews with family members, asking what hearing Ian speak again would mean to them.

He never did make the documentary. Without a miraculous recovery, he felt, the story was just too sad. This past winter, Geoff dug up the old camcorder tapes, and we watched the footage together on the living-room TV. He hadn’t seen it since he filmed it nearly 20 years ago. “Tough to watch,” he said more than once.

After Ian went home, life at the Rainbow Lodge went on largely as it had before. Something did change, though—specifically for Geoff. Knowing that scientists now believed Ian retained some awareness transformed how he related to his younger brother. He started spending more time with Ian, and the two regained a brotherly intimacy. “Ian, are you conscious or are you a vegetable?” Geoff teased during one of my visits. “I think you’re a vegetable. I think you look like a kumquat.”

Geoff eventually took on more and more of Ian’s care; he is now paid through Medicaid as a part-time caregiver, helping Eve, who is 86. Geoff is the one who puts Ian to bed every evening, smoothing out the sheets to make sure he does not lie on a wrinkle all night long. He tucks an extra pillow on Ian’s left side, as his head has a tendency to droop that way.

For Eve, caregiving came naturally; she told me her ambition in life was always to be a mother. She had married at 18 and had three children in quick succession. When their marriage became strained, she and her first husband decided to try an open relationship. In 1964, Eve got a job waitressing at a Woodstock café whose owners let a singer named Bob Dylan live upstairs. She flirted with men. She flirted with Dylan, who took her to play pool and showed her pages of his book in progress, Tarantula. (“Bob was much cuter,” she says of Timothée Chalamet, who starred in the recent Dylan biopic.) Eventually she got divorced; her second husband was Ian’s father. Her third, Marshall, was an artist with a successful marketing career in New York City. Eve and Marshall planned to spend more time there after Ian graduated. The car crash upended everything.

Afterward, Eve threw herself back into the role of devoted mother. (Marshall helped take care of Ian until his death in 2011.) Even now, with Geoff and two nurses who cover five days a week, Eve has certain tasks she insists on carrying out herself. She trims Ian’s nails and hair, now thinning on top to reveal the faint scars from his deep-brain-stimulation surgery. She shaves him. When she speaks to her son, she leans over close, their matching Roman noses almost touching. In these moments, Ian will vocalize—“Aaaaaahh ahhhhhh”—like he is trying to talk with his mother.

“I think Ian lived for my mom,” Geoff told me at one point, thinking back to the hospital, where Eve pleaded over his unconscious body, holding on to Ian with her imagined golden lasso. She had promised Ian then that she would do anything for him if he lived—hence the healers, the studies, and her devotion to him for the past 39 years.

While Ian was recovering from the deep-brain-stimulation surgery, Eve came across a poem by E. E. Cummings that affected her so deeply, she took to reading it aloud to him in a morning ritual. The second stanza goes:

(i who have died am alive again today,and this is the sun’s birthday;this is the birthday of life and of love and wings:and of the gaygreat happening illimitably earth)

Schiff kept probing the outer limits of consciousness in patients with severe brain injuries. Last year, he, along with Owen, Laureys, and other researchers in the field, published the largest and most comprehensive study yet of covert awareness. This is the New England Journal of Medicine study that included Ian, and found one in four vegetative or minimally conscious brain-injury patients to have covert awareness. (Schiff prefers the term cognitive motor disassociation, to highlight the disconnect between the patients’ mental and physical abilities.) “Our experience was Wow, it’s not so hard to find these people,” Schiff told me.

The researchers do not believe that everyone with a disorder of consciousness is somehow cognitively intact—a majority are probably not, according to this study. The most important takeaway, researchers say, is simply this: People with covert awareness exist, and they are not exceedingly rare.

These findings raise profound questions about our ethical obligation to people with severe brain injuries. In his 2015 book, Rights Come to Mind, Joseph Fins, a medical ethicist at Cornell who frequently collaborates with Schiff, argues that such patients deserve better than to be “cast aside by an indifferent health care system,” or left to languish as mere bodies to feed and clean. “For so long, I’d been stripped of any identity,” one brain-injury patient, Julia Tavalaro, wrote in her memoir, Look Up for Yes. “I had begun to think of myself as less than an animal.” She was able to write the book after a particularly observant speech therapist finally noticed, six years after her injury, that she could communicate with her eyes. But too often, Fins told me, patients are shunted into long-term-care homes that cannot provide the attention and rehab that could uncover subtle signs of consciousness.

These patients are also especially vulnerable to abuse. In 2019, staff at a facility in Phoenix called 911 in a panic after a patient—who was reportedly vegetative but may have been minimally conscious—unexpectedly gave birth. No one at the facility, where she had lived for years, even knew she was pregnant until a nurse saw the baby’s head. She had been raped by a male nurse.

In some cases, patients with covert awareness may never make it to long-term care—they simply die when life support is withdrawn at the hospital. “If you went back 15, 20 years, there was a tremendous amount of nihilism” among doctors, says Kevin Sheth, a neurologist at Yale. Even as medicine has become less fatalistic about brain injury, hospitals still rarely look for covert awareness using fMRI. ICU patients may be too fragile to be moved to an fMRI machine, and the technology is too cumbersome and expensive to bring into the ICU.

Varina Boerwinkle, a neurocritical-care specialist now at the University of North Carolina, believes the technology should be routinely used with brain-injury patients. She told me about a 6-year-old boy she treated at a previous job in 2021, who had been in a car crash. Her initial impression was that he would not survive, and his first fMRI scan showed no signs of awareness. Boerwinkle began to wonder if doctors were prolonging his suffering. But the team repeated the test on day 10, in anticipation of discussing withdrawal of care with the boy’s parents. To Boerwinkle’s astonishment, his brain was now active: He could respond when asked to perform specific mental tasks in the fMRI.

At first, Boerwinkle wasn’t sure what to say to the boy’s family about the fMRI. Though it implied that he still had cognitive function, it did not guarantee that he would ever recover enough to respond physically or verbally. Her colleagues have seen families struggle to care for a child with a severe brain injury, Boerwinkle told me, and everyone was wary of providing false hope.

The doctors ultimately did inform the boy’s parents about their findings; his mother told me the fMRI gave them the confidence to agree to another surgery. It worked. Four years later, the boy is back in school. He uses an eye-gaze device to communicate and zoom around in his wheelchair, and his reading and math skills are on par with those of other kids his age.

Scientists are now looking for simpler tools to test for covert awareness. Patients who show signs of awareness early on, it seems, tend to have better recoveries than those who don’t. Owen, now based at the University of Western Ontario, recently published a study using functional near-infrared spectroscopy, which shines a light through the skull. A group at Columbia University, led by Jan Claassen, is experimenting with EEG electrodes that sit on the head.

But even after 20 years of research, little has changed in terms of what doctors can do to help patients found to have covert awareness long after their injury—which is still, in most cases, nothing. On his office wall, Schiff has taped the brain scans of five patients to remind him of the human stakes of his work. He is now exploring brain implants, which are already helping certain paralyzed patients control cursors with their mind or speak via a computer-generated voice. The next several years could prove crucial, as a crop of well-funded companies tests new ways of interfacing with the brain: Elon Musk’s Neuralink, perhaps the best-known of these, uses filaments implanted by a sewing-machine-like robot; Precision Neuroscience’s thin film floats atop the cortex; and Synchron’s implant is threaded up to the brain through the jugular vein.

Getting any of these implants to work in people with severe injuries like Ian’s will be particularly challenging. Ian’s age and the electrodes already implanted in his brain also make him an unlikely early candidate. This technology—if it ever works for people like him—may arrive too late for Ian.

Even in 1972, when Plum and Jennett first described the vegetative state, the doctors foresaw that they were barreling toward a “problem with humanitarian and socioeconomic implications.” The vegetative patients they described could now be kept alive indefinitely—but should they be? At what cost? Who’s to decide? Soon enough, Plum himself was asked to weigh in on the life of a 21-year-old woman.

In 1975, Plum became the lead witness in the case of Karen Ann Quinlan, who’d recently fallen into a vegetative state. She had collapsed after taking Valium mixed with alcohol, which temporarily starved her brain of oxygen. Her parents wanted her ventilator removed. Her doctors refused. In the ensuing legal battle, Quinlan’s family and friends testified that she had said, in conversations about people with cancer, that she wouldn’t want to be “kept alive by machines.” But there was no way to know what Quinlan wanted in her current condition. Plum categorically pronounced that she “no longer has any cognitive function”; another doctor likened her, in his court testimony, to an “anencephalic monster.”

In the end, a court granted her parents’ request to remove Quinlan’s ventilator. The controversy surrounding her case fueled interest in then-novel advance directives, which allow people to spell out if and at what point they want to die in the event of future incapacitation. In recognizing that life might not always be worth living, the court’s ruling also inspired a nascent “right to die” movement in the U.S.

By the time Terri Schiavo, in Florida, made national news in the early 2000s, resurfacing many of the same legal and ethical questions, the science had become more complicated. Schiavo had also been diagnosed as vegetative after she collapsed—from cardiac arrest, in her case. When her condition did not improve after eight years, her husband sought to have her feeding tube removed. Her parents fought back, fiercely. Although most experts found her to be vegetative, those aligned with her parents seized on the newly defined minimally conscious state to argue that Schiavo was still aware. The family released video clips purporting to show her responding to her mother’s voice or tracking a Mickey Mouse balloon with her eyes. If she was still conscious, they argued, she should not be made to die.

Schiavo became a cause célèbre for the religious right, and opinions hardened. Where one side saw parents honoring their daughter’s life, the other saw them clinging to illusory hope. Giacino told me that because of his key role in defining the minimally conscious state, he was asked to examine Schiavo by the office of Jeb Bush, then Florida’s governor. The behavioral exam he planned to perform, Giacino said, could have helped discern whether Schiavo’s responses were real or random. He never did go to Florida, though, because a court proceeding made another exam moot.

Schiavo eventually died when her feeding tube was removed in 2005. The general consensus now holds that she likely was vegetative—an autopsy later found that her brain had atrophied to half its normal size—but Giacino still wonders how that correlated with her level of consciousness. Because he never examined her himself, he personally reserved judgment.

If Schiavo—or let’s say a hypothetical patient diagnosed as vegetative, like her—were in fact minimally conscious or covertly aware, would that tip the calculus of keeping her alive one way or the other? Which way? On one hand is the horrifying proposition of snuffing out a human consciousness. On the other hand is what some might consider a fate worse than death, of living imprisoned in a body entirely without choice, without freedom. In memoirs and interviews, brain-injury patients who regained communication—Tavalaro among them—speak of despair, of abuse, and of sheer, uninterrupted boredom. They could not even turn their head to stare at a different patch of wall paint. One young man described the particular agony of being placed carelessly in a wheelchair and forced to sit for hours atop his testicles. Some have tried to end their life by holding their breath, which turns out to be physically impossible. The classical notion of a totally mindless vegetative state offered at least meager solace: a person devoid of consciousness would not experience pain or suffering.

One-third of locked-in patients, who can communicate only using their eyes, have thought of suicide often or occasionally, according to a survey of 65 people conducted by Laureys, the Belgian neurologist. But a majority of these patients have never contemplated suicide. They say they are happy, and those who have been locked in longer report being happier, which squares with other research showing that people with disabilities are in fact quite adaptable in the long term. Of course, those who responded to the survey are not entirely representative of everyone with a brain injury; for one thing, they could still communicate, albeit with difficulty.

What about covertly aware patients, with total loss of communication—are they happy to be alive? As far as I know, only one such person has ever had the opportunity to answer this question. In the 2010 study, after the 22-year-old man answered five consecutive yes-or-no questions correctly, Laureys decided to pose a last question, one to which he did not already know the answer: Do you want to die?

Where the man’s previous responses were clear, this one was ambiguous. The scan suggested that he was imagining neither tennis nor his house. He seemed to be thinking neither yes nor no, but something more complicated—exactly what, we will never know.

I posed a version of this question to the researchers who have devoted their career to understanding disorders of consciousness. Would you choose to live? “If no one was coming to the rescue, if help was not on the way, I wouldn’t want to be in any of these situations,” said Schiff, who has a practical eye toward brain-implant research that could one day help these patients.

Owen was more philosophical. He told me that when people learn about his research, many say they would prefer to die; even his wife says that. But he is less certain. He does not have an advance directive. Perhaps the only thing worse than wanting to die and being forced to live, he said, is to watch everyone let you die when you have decided, in the moment of truth, that you actually want to live.

On one of my trips to the Rainbow Lodge this past winter, Geoff rigged up Ian’s foot switch—one of countless assistive devices his family has tried—to play a prerecorded message for me. “Hey, Sarah, thanks for coming!” it went in Geoff’s singsong voice. “I’m glad to see ya.” His family had hoped, at one point, that Ian’s left foot, which waves back and forth, unlike his permanently fixed right one, could become a mode of communication. But Ian has never been able to push the switch reliably on command. Still, occasionally, he hits the big green button just hard enough to set it off.

I cannot know to what extent, if any, this movement is voluntary. But Ian’s foot is certainly more active at some times than others. While his family and I chatted over lunch at the kitchen table one day, it went tap, tap. “Hey, Sarah, thanks for coming!” Was he trying to join the conversation? “Hey, Sarah, thanks for coming!” If so, what did he want to say?

There was one other instance when I saw his foot moving that much—during a previous visit, when we spoke in detail about Ian’s car crash for the first time. The crash took place in the early morning, after the boys had been together all night. Ian was driving. When Eve was asked to identify the body of the boy who died, Sam, she recognized the white shell necklace Ian had brought back for him from a recent trip to Florida. The third boy—the one who survived—eventually stopped keeping in touch with high-school friends, a disappearance they attributed to survivor’s guilt.

I wondered if our conversation would distress Ian, if we should be replaying these events in front of him. To me, it seemed as though his face had turned especially tense. His foot was going tap, tap, tap. Or was I projecting my own thoughts, as it is so easy to do with someone who cannot respond? “Ian knows he killed his best friend,” Geoff said at one point that night. “By accident.”

The next day, Ian was grinding his teeth. It happens sometimes, Eve told me. Perhaps something hurt. Or his stomach was upset. Or an eyelash was stuck in his eye. They tried to rule out causes one by one, but it’s always a guessing game. I thought back to our conversation the night before, and wondered whether the presence of a stranger probing the traumatic events of his life might have agitated him.

Ian could not walk away from a conversation he did not want to have, nor could he correct the record of what we got wrong. If his memories and cognition are more intact than not, then he has had time—so much time—to live inside his own thoughts. Has he come to his own reckoning over his friend’s death? Does he feel his own survivor’s guilt? Does he ever wish for the fate of one of his friends in the car over the one he was actually dealt? Perhaps being incapable of these thoughts would be a mercy in itself.

At one point, Geoff decided to reprogram Ian’s foot switch, in part to cheer up Molly Holm, one of Ian’s nurses since 2008, who had bruised her ribs slipping on ice. Molly had known Ian back in high school; he was friends with her older brother. She started coming to patterning sessions at the Rainbow Lodge after the accident, taking a position at Ian’s right hand. She later became a nurse. Her first job was at a head-trauma center, where she looked after young men with injuries like Ian’s. In some of the vegetative patients, she would see flashes of what seemed like awareness. But who was she, a very green nurse, to question a doctor’s diagnosis? Some of the men at this facility rarely had visitors, Molly says, their isolation so unlike the warmth of Ian’s home.

That’s what originally drew her, a deeply unhappy 14-year-old, to the Rainbow Lodge all those years ago. (Okay, she admits, she’d also had a huge crush on Ian before the crash.) It drew other people too, including those who temporarily moved into the lodge’s guest rooms during the patterning days: Ian’s girlfriend, Valerie Cashen; a friend of Geoff’s, Karen McKenna, who was 21 and pregnant, and had recently split from her boyfriend; and, perhaps most unexpectedly, the mother of the boy killed in the car crash, Renee Montana. Eve had overheard her primal scream of grief in the hospital, and when they later met, the mothers felt connected rather than divided by their respective tragedies.

Valerie, Karen, and Renee all arrived at the Rainbow Lodge overwhelmed by their own life circumstances. The two younger women stayed for a year or two and became close friends. Karen hadn’t known Ian at all before his injury. She first came to the hospital as a friend of the family; she offered to watch over Ian for Eve because, well, she didn’t have much else to do. She gave birth to her baby while living at the lodge, Eve by her side as her Lamaze coach. Karen’s time caring for Ian helped inspire her to enroll in nursing school, and she eventually became a nurse at the very ICU where she first met Ian.

Renee stayed for a few years. She did not blame Ian for Sam’s death, though she knew that others did. When I asked her if she ever thought about what might have happened if their fates had been switched, she had an immediate answer: “My poor boy would have been institutionalized.”

She didn’t have the means to care for him at home; she didn’t have the Rainbow Lodge. She was a single mom, living with a boyfriend in a disintegrating relationship. Eve and Marshall’s welcoming her into their community kept her from going adrift. “They just saved my life,” she said. Her life took an unexpected turn there too: Renee ended up having another child—her daughter, Morganne—born in 1988, after Renee had a brief affair with Eve’s brother.

Out of these chaotic circumstances, Eve and Renee found their bond as new friends cemented into that of family. Eve was present at this birth as well; she cut Morganne’s umbilical cord. Back at the lodge, they put the newborn girl in Ian’s lap, letting him hold a new life that would not exist had his own not been thrown off course. Morganne, now 37, told me that her earliest memories are of curling up at Ian’s feet to watch TV.

Reflecting on life after Ian’s accident, Eve prefers to speak not of loss but of gains: a new niece, lifelong friends, the entire Rainbow Lodge community. She decided long ago that she could carry others forward—Ian most of all—on her brute optimism. And in our hours of conversation, I never heard her linger on a negative note.

In this respect, Geoff does not take after his mother. “Geoff’s more like, I see your suffering, brother,” Molly told me. He and Ian have a different kind of bond, she added, “because Geoff recognizes that, sometimes, this sucks.”

“No, I mean, it definitely sucks, right?” Geoff said. “Not to be able to communicate sucks.”

Geoff’s coping mechanism is humor, at times dark, at times juvenile. It helps that Ian’s most reliable response is laughter. When he really gets going, his chuckle turns into a full chest shake. Geoff still dreams about the technology that might help his brother communicate. For now, they have the foot switch.

The message Geoff recorded after Molly’s fall was meant to make her, and everyone else, laugh: He blew a fart noise, scattered objects on the ground, and shouted, “Oh my God! What happened there?” Then he slipped the switch under Ian’s left foot.

Geoff was so keen to lift Molly’s spirits because they are a couple, together since 2000. Over the course of their relationship, Geoff had grown close to another of her patients, a spunky boy who eventually died of epidermolysis bullosa, also known as butterfly-skin syndrome, in his 20s. They don’t have children of their own but they had become a caretaking unit, their relationship deepening over their shared love for the boy. Now they care for Ian together, and they will continue to care for him when Eve is gone.

When I was leaving the Rainbow Lodge for the last time, Eve impressed upon me what she hoped people would take away from Ian’s life: “It’s not a sad story.” On this, Molly concurred. Yes, it sucks sometimes. But Ian has been continuously surrounded by people who love him, people who took that love and made something of it.

As if on cue, Ian’s foot switch went off. Fart noise. Objects scattering. “Oh my God! What happened there?” Maybe it was just a random movement of his foot. Maybe he wanted to disagree with his mother’s assessment. Or maybe he agreed that his is not a sad story. If only he could tell us in his own words.

This article appears in the June 2025 print edition with the headline “Is Ian Still In There?” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

The post Is Ian Still In There? appeared first on The Atlantic.