When the Supreme Court hears arguments Thursday over President Trump’s challenge to automatic birthright citizenship, the immigration spat could take a backseat to a more contested legal question about the power of lower-court judges to rein in the executive branch.

Earlier this year, lower courts in Washington, Massachusetts and Maryland slapped broad universal injunctions — nationwide pauses — that stopped Trump’s executive action to end birthright citizenship from taking effect.

Back in March, the Trump administration pleaded with the high court and is hoping to use the birthright citizenship case to end “toxic and unprecedented” universal injunctions that have hampered a myriad of the president’s executive actions.

“This is a funny test case, because the underlying law is so clear and because it’s sort of the same exact issue all across the country,” Gabriel Chin, a Martin Luther King Jr. Professor of Law, and Director of Clinical Legal Education at the UC Davis School of Law, told The Post.

“I’m actually a little surprised that the Supreme Court took it.”

Many legal scholars, including Chin, believe the underlying merits of the Trump administration’s challenge against birthright citizenship are on shaky grounds because of the clear text of the 14th Amendment, which guarantees citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States.”

A key objective behind the drafting of the 14th Amendment was to ensure that freed slaves obtained citizenship.

The Supreme Court previously backed the birthright citizenship interpretation in 1898.

“The case against the executive order or in favor of universal birthright citizenship is extraordinarily strong from the text of the Constitution, which is clear, to the framers intent,” said Amanda Frost, a law professor at the University of Virginia School of Law.

She warned that if birthright citizenship gets overturned, it could have a significant impact on the roughly 3.6 million Americans having babies each year, who may have to prove their children’s lineage and citizenship status.

A group of 22 states, seven plaintiffs, and two immigration organizations had sued over Trump’s actions on birthright citizenship.

Three appeals courts shot down the administration’s attempts to reverse the injunctions.

While justices on the Supreme Court haven’t spoken much about birthright citizenship, many of them from all ideological corners of the bench have raised concerns about nationwide injunctions.

During Trump’s first term, conservative Justice Clarence Thomas suggested in a concurring opinion on the president’s travel ban that the high court may need to reevaluate lower court use of nationwide injunctions.

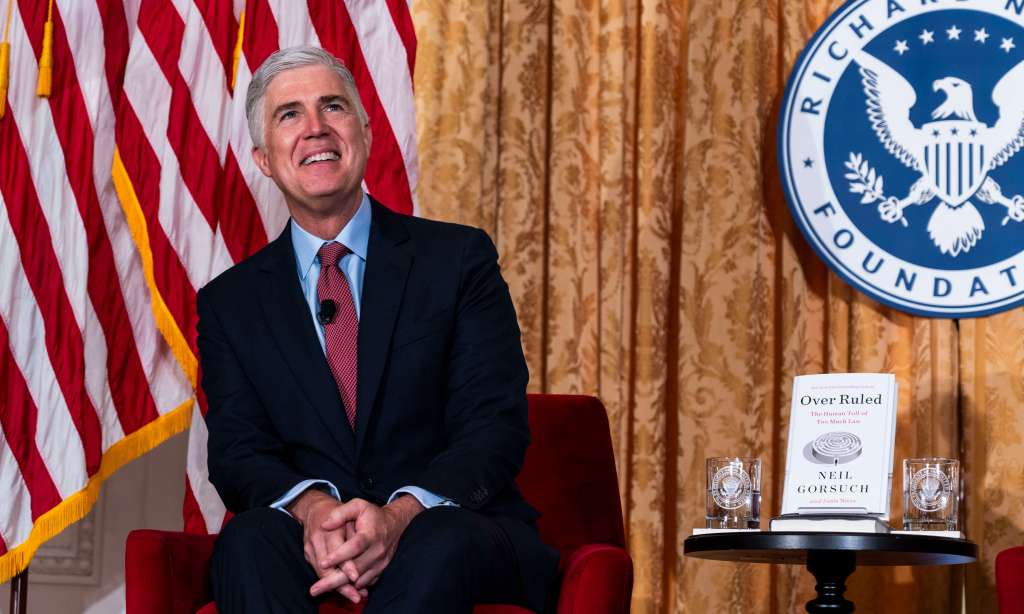

Fellow conservative Justice Neil Gorsuch argued in a different case that “routine issuance of universal injunctions is patently unworkable.”

Liberal Justice Elena Kagan publicly said in a 2022 university speech that “It just can’t be right that one district judge can stop a nationwide policy in its tracks and leave it stopped for the years that it takes to go through the normal process.”

Her liberal peer, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson suggested in an opinion last year that the high court needs to look into universal injunctions but cautioned the solution wasn’t “straightforward.”

No one is entirely sure why the Supreme Court decided to take up the birthright citizenship case as the vehicle to reevaluate lower court use of universal injunctions.

Some analysts have suggested the high court would’ve had an easier time clawing back the scope of injunctions on a case where the defendants were likely to prevail on the merits.

“The court isn’t really telling us very much about what it’s doing in this context at all. It hasn’t granted certiorari — it hasn’t said that it will specifically answer a particular constitutional question,” said Evan Bernick, an associate law professor at the Northern Illinois University College of Law.

“The effect of saying some of these injunctions have to be vacated because they’re too broad [or] because federal courts don’t have this power means that a policy that is unconstitutional on the merits will go into effect for some time.”

Ilya Somin, B. Kenneth Simon Chair in Constitutional Studies at the Cato Institute, is wondering which of the justices decided to take up the case in the first place.

“One interesting question is whether this case was chosen by a group of justices who would want to limit or get rid of universal injunctions, or whether it was chosen by a group of justices who want to do the opposite,” Somin mused.

Somin is currently involved in litigation against the Trump administration over tariffs and hopes to win a universal injunction to pump the brakes on the president’s protectionist venture.

“My theory is that this particular executive order is a gift to Chief Justice Roberts, because Chief Justice Roberts will be able to ultimately strike this down with a majority, and that will make him look like a moderate and reasonable because he’s also going to write a bunch of opinions upholding other executive orders and other actions of the administration,” Chin speculated.

Roberts is widely seen as an intuitionalist who is very mindful of the high court’s reputation.

In March, a study found that lower courts lodged at least 15 national injunctions against Trump.

That dramatically outpaces the six against former President George W. Bush, 12 against former President Barack Obama and 14 against former President Joe Biden during their entire presidencies, per a tally from Harvard Law Review.

Trump administration attorneys argued in a petition to the Supreme Court that “Universal injunctions have reached epidemic proportions since the start of the current Administration.”

“What we have is an epidemic of nationwide illegal actions by this administration, and in fairness, to some degree by the previous administration as well,” Somin argued.

“If you engage in rampant illegality that’s nationwide in scope, then you can expect to get nationwide remedies imposed against you.”

Acting US Solicitor General Sarah Harris had asked the Supreme Court to consider narrowing “limiting those injunctions to parties actually within the courts’ power.”

In other words, the Trump administration believes lower courts should only be able to block his actions to scrap birthright citizenship from impacting their specific jurisdiction rather than the nation writ large.

“Would the federal judiciary be better off if there had to be litigation brought in in 12 circuits?” Chin pondered.

“It’s not clear that this is the best test case to show the problem of universal injunctions.”

After finishing oral arguments, the Supreme Court is expected to hand down a decision in the consolidated Trump v. CASA Inc case.

Oral arguments on the matter are expected to be the high court’s last of this term and the issue is one of the most controversial cases currently on its docket, alongside a challenge against Tennessee’s laws on transgenderism.

The post Why Trump’s Supreme Court challenge against birthright citizenship may not really be about birthright citizenship appeared first on New York Post.