Professional baseball has a pitching crisis, as its starters throw harder and faster—and get injured more often. In search of what’s gone wrong with a pillar of this beautiful game, I drove along Lake Hartwell, in South Carolina, and pulled into a dirt driveway, where a baseball wizard by the name of Leo Mazzone greeted me. From 1990 to 2005, he oversaw the Atlanta Braves’ pitching staff, one of the greatest in history. He’s long been dismayed by Major League Baseball’s relentless focus on analytics and what it has done to pitchers, and I figured I would give him a chance to say I told you so.

I asked Mazzone: What happened?

“All anyone in the majors watches now is how damn fast a guy can throw,” he told me, rocking on his heels. “Grunt and heave, grunt and heave. It’s not pitching; it’s asinine.”

He chuckled.

“You see guys with these crazy-violent deliveries, spinning out on the mounds. Would I trust these guys in a game? Sheeit.”

Mazzone, 76, lives in a retirement exile, ignored by the Ivy League quants who now dominate teams’ front offices. In December, though, Major League Baseball released a report that implicitly acknowledged the core truths of Mazzone’s critique. The emphasis on throwing as hard as possible on every pitch is likely ruinous for a pitcher’s ligaments, the report found, and has led to a sharp increase in elbow surgeries. A pitcher’s craft is reduced to optimizing his “stuff”—arcane computer-driven metrics such as spin rates, horizontal and vertical breaks, and radar-gun-certified speed.

Beyond putting pitcher health at risk, this insistence results in boring, plain-ugly baseball. Pitcher workdays come with strict limitations. Two decades ago, after injury rates began to climb, teams imposed a limit of 100 pitches a game, and that somewhat arbitrary threshold yielded to limits of 90, 80, and even 70 pitches—meaning that most starters leave the pitching mound after five innings, before being replaced by largely anonymous relievers who are also throwing as hard as they can.

“The focus on velocity, ‘stuff,’ and max-effort pitching—have caused a noticeable and detrimental impact on the quality of the game on the field,” the report observed. “Such trends are inherently counter to contact-oriented approaches that create more balls in play and result in the type of on-field action that fans want to see.”

So far, though, the report hasn’t changed anything, perhaps because the fixation on pitch velocity and spin rates has become entrenched throughout the sport, from youth travel baseball to college to the majors. Electronically clocking a prospect’s fastball, and analyzing the arm and wrist torque that causes a ball to spin, is easier than forecasting whether he has the mental discipline and control needed to thrive for years in the majors. Front offices may calculate that burning through little-known relievers is cheaper and easier than finding and nurturing future stars.

More than two decades into the sabermetrics era, baseball evinces what is obvious in many fields: Fixating on statistics changes everything, and not always for the better. Pitching is not math; it’s an art.

Mazzone still advises college coaches and speaks at youth baseball conventions. He shudders when he sees young pitchers lift barbells and hurl weighted baseballs at walls. “The game now is all about speed,” he said, “and it’s all bullshit.”

Mazzone grew up in the rural sawmill town of Luke, Maryland, and labored for 10 years as an itinerant Minor League pitcher, including a stint in Mexico with the Guaymas Oystercatchers. As a Minor League coach for the Braves, he found a mentor in Johnny Sain, a perpetual rebel and pitching savant. Sain had tutored baseball’s best pitchers and insisted that they concentrate less on brute strength than on varying speeds and the location where the ball crossed home plate. “Every night he took me to his RV and fired up his grill, and we’d have a sip or two and just talk pitching,” Mazzone recalled. “I wondered about all the dumbasses who would not listen to this man.”

From Sain, Mazzone learned the elements of his pitching gospel. “All of our efforts were put on movement, change of speeds, location. Velocity was No. 4 on that list,” he said. Mazzone settled on simple rules: A good pitcher should throw at 85 percent of his full effort and learn to save his best for late in the game.

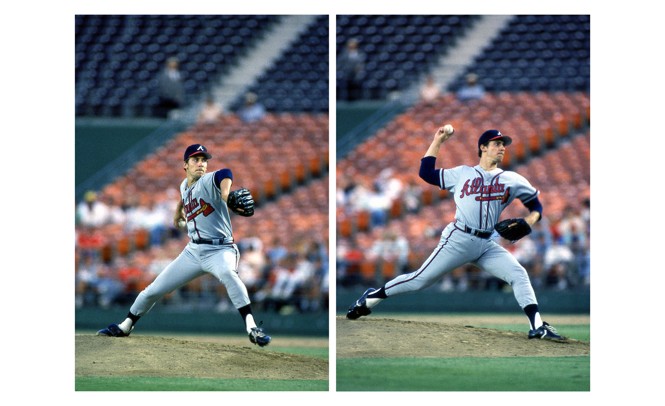

Mazzone was elevated to Braves pitching coach. His three best starters, Greg Maddux, John Smoltz, and Tom Glavine, won a total of six Cy Young awards as the best pitcher in the National League during Mazzone’s tenure in Atlanta and strolled into the Hall of Fame. He worked his magic on many other starting pitchers, whose careers were revived with the Braves. Some baseball writers and historians argue that Mazzone, for his wisdom and innovation, belongs in the Hall too.

Mazzone left the Braves in 2005 and served as pitching coach for the Baltimore Orioles, grooming some fine starting pitchers. After the Orioles fired him in 2007, Mazzone was prematurely retired, his strong opinions and barbed wit doing him no favors with front offices.

For more than a century, the starting pitcher was a favored prince. Tom Seaver, Bob Gibson, Juan Marichal, Justin Verlander, Steve Carlton, Pedro Martinez, Jim Palmer, Randy Johnson: To rattle off these names is to conjure up that lovely baseball pleasure, the solitary duel between a great pitcher and a great hitter.

I recall as a kid watching on a black-and-white television the 1973 World Series between my beloved New York Mets and the Oakland A’s. There was Seaver, with that relentless drop-and-drive delivery of his, facing off against Reggie Jackson, the swashbuckling Oakland slugger—darting fastballs and curves matched against a magnificent swing.

Batting styles have also changed since then, with much emphasis put on hitting with power, preferably home runs. Strikeouts have spiked sharply, and batting averages have plunged.

Mazzone does not care for that: more dullness. He’s not opposed to computer analysis as a tool in a coach’s arsenal. But his pitching credo had little to do with 100-miles-an-hour fastballs and the obsessive monitoring of pitch counts and spin rates. Mazzone has no patience for the conventional wisdom that pitchers tire and struggle on the third time through an opposing lineup, in the sixth or seventh inning.

Mazzone told me that his most reliable pitchers played well late in games. “The key was controlling the amount of effort,” he said.

In 1987, the Braves traded a fine but aging starting pitcher, Doyle Alexander, for John Smoltz, who came from the Detroit Tigers’ Minor League system. People chattered that the Braves had been fleeced. Take the kid out back to a pitching mound, then–General Manager Bobby Cox told Mazzone, and tell me what we’ve got. Scouting reports suggested that the 20-year-old Smoltz had a lively but erratic fastball.

Mazzone and the kid walked to a back lot in the Braves training complex. “I told Smoltzy to just throw natural,” Mazzone recalled. On the fourth or fifth pitch, Smoltz shook his head and muttered,: “This ain’t right.”

“What ain’t right?” Mazzone asked.

“Well, my left leg has to go here, and my right leg has to go there,” Smoltz said. “When I was in Detroit—”

Mazzone cut him off. “You’re not in fucking Detroit. Throw natural.”

Smoltz—who has recalled their conversation similarly—calmed down and tossed one fastball after another across the plate, beautiful as could be. From there, Mazzone worked on developing Smoltz’s off-speed pitches.

A year later, Smoltz reached the majors at age 21. A year after that, he pitched more than 200 Major League innings. “I said to myself, Damn, this was too easy,” Mazzone recalled.

Although Mazzone kept a clicker in his pocket to count pitches, he is no fan of that stat. From Seaver to Nolan Ryan to Ferguson Jenkins, many great pitchers threw more than 270 innings in multiple seasons—which meant they tossed well in excess of 100 pitches a game. Yet the record shows that most of them, particularly at their career peak, were harder to hit in later innings than earlier in the game. Mazzone’s top Braves pitchers averaged 200 to 250 innings a year and rarely missed games because of injuries. “My greatest satisfaction was the health of my staff,” he said. “We gave them a chance to earn their money.”

Even when Mazzone counted pitches, he was purposely erratic about the count, he gleefully admits. He wanted to teach his pitchers to work through fatigue without resorting to trying to muscle pitches by a batter. Far better to rely on good form and guile. “Hell, I used to cheat,” he said, cackling. “Smoltzy would come off the mound and say, ‘I’m a little tired’ and I’d say, ‘Geez, that’s strange—you’ve only got 60-something pitches.’”

Cox caught on: “Bobby Cox would ask me, ‘Is that the real pitch count or is that fucking yours?!’” Cox, who had the fourth-highest win total in history as a manager, was not much more enamored of data. Because of him, Mazzone said, the Braves stadium was the last in the majors to install a digital screen showing the count and speed of pitches.

Quants would counter that trying to return to Mazzone’s era would be folly. Hitters have more sophisticated workout regimens, and the emphasis on swinging up on the ball to hit home runs has changed the game. To ask a pitcher to throw at less than maximum effort is to risk getting clobbered.

But many successful pitchers have eschewed that ethos. In 2016, I watched Bartolo Colon pitch for the Mets at age 43, well past the point when most pitchers have retired. A portly fellow, he threw a fastball that was notably slow and more often traveled in the mid-80s. Yet he artfully varied speeds and hit his spots, and pitched nearly 200 innings and finished 15–8.

Compared with today, pitchers were at a far greater disadvantage in the ’90s and 2000s—baseball’s Frankenstein Era, when steroids were rampant among power hitters and home-run totals soared. Yet in 2000, the relatively diminutive Pedro Martinez (5 foot 11 and 170 pounds; known for his exquisite control) pitched 217 innings for the Red Sox, struck out 284 men, and posted a record of 18–6 with a microscopic 1.74 earned-run average. In the National League that same year, Maddux, then 34 and past his prime, pitched 249 innings and finished 19–9—even though, Mazzone recalls, his fastball rarely edged past 90 miles an hour.

If, in that most hostile era, the best pitchers could control the strike, today’s pitchers have nothing to fear. “Hitters are bigger and stronger, but they make less contact than ever,” Mazzone said. “That’s good for pitchers!

Mazzone’s motor never stops. When he was with the Braves, he rocked back and forth on the bench. The more intense the game, the faster he rocked. As we sat in his study—lined with uniforms, signed baseball photos, championship rings, and bats and balls—and talked about recent pitching foolishness, his voice rose, and he rocked in his chair. He dismissed any suggestion that he was stuck in the past. He endorsed recent reforms intended to liven up the game that has slowed down dramatically in the sabermetrics era.

He likes the pitch clock, which gives pitchers no more than 15 to 18 seconds between throws. Starters, he said, should adhere to a brisk pace. And he has made peace with the decision to start extra innings by placing a man on second base. “It adds strategy,” he said.

But he’s no optimist about the future of his beloved starting pitchers. From the majors to youth Pony League, a mania for speed predominates, as if everyone has purchased stock in radar-gun makers. “I talk to youth leagues and warn them: Never talk about velocity to your kids,” he said. “Then I take questions, and it’s all about speed.”

When I interviewed Mazzone several years ago, he recounted how Maddux had once tried to explain to young Braves pitchers during spring training how old-fashioned craft could lead to fantastical riches. “You know why I am a millionaire? Because I can put my fastball wherever I want to,” Maddux had said. “Do you know why I own beachfront property in L.A.? Because I can change speeds. Okay, questions?”

I asked Mazzone: What would happen if Maddux gave that speech today? Mazzone scoffed. “They’d nod,” he said, “and go back to throwing weighted baseballs at walls and trying to throw 100 miles per hour.”

The post An Old-School Pitching Coach Says I Told You So appeared first on The Atlantic.