San Francisco has boomed in many ways over the past two decades, but while the city has become a hub for tech talent and entrepreneurship, it has also gained a negative reputation for a high crime rate.

That is, until the past year, when the city saw a staggering drop in reported crime, which is continuing in 2025.

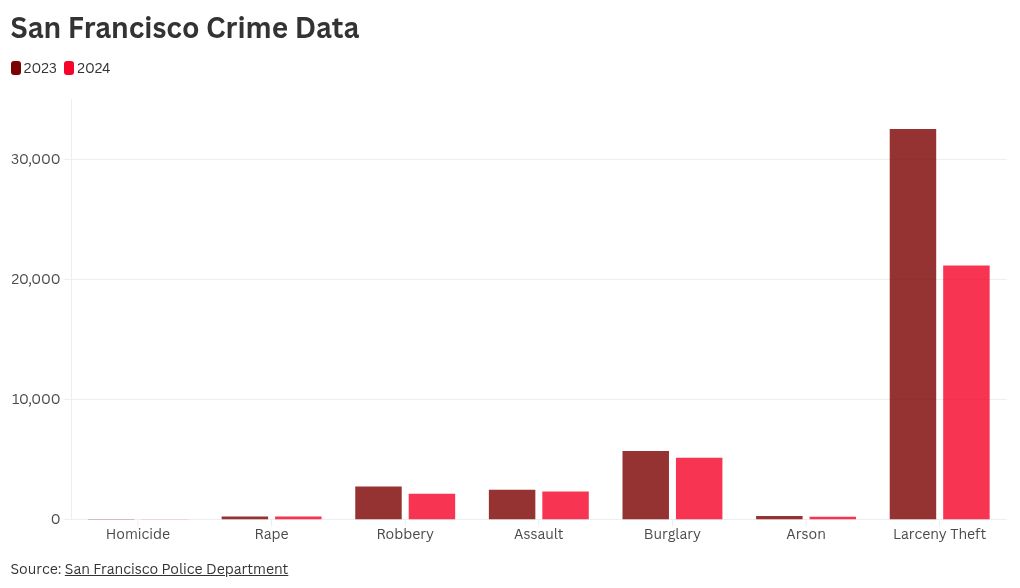

The San Francisco Police Department (SFPD) reported that in 2024, homicides in the city fell by 31.4 percent, rapes fell by 2 percent and robbery fell by 21.8, compared to 2023.

Additionally, assaults fell by 6.3 percent, burglary and larceny theft fell by 9.9 and 35 percent, respectively, and arson fell by 20.6 percent in the same time period.

The start of 2025 also appears to be promising in terms of falling crime. SFPD data shows that homicides between January 1 and April 14, compared to the same time period in 2024, fell by 55.6 percent.

That comparative time period also saw rapes fall by 34.2 percent, robberies by 21.2 percent, assaults by 7.3, burglaries by 42.1 percent, larceny-theft by 30.4 and arson by 29.7 percent.

The statistics cover a smaller period of time, meaning the percentage difference may appear larger than the numerical difference between crimes.

San Francisco District Attorney (DA) Brooke Jenkins spoke with Newsweek about the methods being used by her office and San Francisco law enforcement to reduce crime in the city.

“When I was appointed district attorney, we had a complete shift in the way that my office was doing the work and in the partnerships that we had,” Jenkins said. “Particularly with the San Francisco Police Department, but also with our other state and federal law enforcement agencies. Those are partnerships that were very strained, if not nonexistent, before I took over, and so that was a big priority for me.”

Jenkins explained that improving the partnerships between the DA’s office and law enforcement has allowed them to improve court accountability, as she had seen a pattern of people being accused of crimes but not being held accountable.

Without “adequate and appropriate consequences” crime would not be deterred in the city, Jenkins said. However, “we can’t prosecute if the ground-level agencies aren’t doing the work and making the arrest,” she said. “We needed to have a strong partnership, really, to motivate and incentivize them to do more. And we’ve been able to really develop that.”

The collaboration between the offices looks like having regular meetings between the DA and the SFPD, making sure that police are aware of the evidence they need to be gathering at a crime scene so they meet the burden of proof at trial, and Jenkins “giving them praise very publicly because they need to feel encouraged and [that] people see the work that they’re doing and how hard they are working.”

Jenkins spoke specifically about drug arrests. She told Newsweek that San Francisco is perceived as having a permissive drug culture, as there are many people who were able to do drugs openly on the street in the city for many years.

Her office, in conjunction with law enforcement, has been increasing arrests for drug dealing, which Jenkins said may be classified as a non-violent crime but “begets violence” in the form of turf wars, robberies and assault.

When it comes to drugs in the city in particular, Jenkins recognized that they cannot be dealt with purely by carceral means.

“I think one of the largest issues that we face in San Francisco is both the unhoused, the homelessness issue,” she said. “Many of those individuals are addicted to drugs, particularly right now, fentanyl.

“And so there is a lot that we are trying to do to get in front of the law enforcement involvement, to try to route these individuals into treatment, to get them incentivized to engage in treatment.”

Jenkins explained that her office has the opportunity to send drug offenders to collaborative, noncriminal, courts to address their mental health, substance abuse or other struggles in order to get them placed in treatment centers as opposed to prison.

“We do really try to make sure that we address the underlying issue that somebody is facing, both before they enter the criminal justice system and have contact with law enforcement,” Jenkins said.

This is an effort that has not gone unnoticed by social justice groups in San Francisco.

GLIDE, a social justice organization in the city dedicated to combating poverty and systemic injustice, spoke with Newsweek about the city’s new strategy toward crime.

“The shifting public safety landscape has brought both opportunities and complexities to our work: fewer reported crimes can create a safer environment for our clients and staff, but higher arrest rates, depending on how they are applied, can also increase the vulnerability of marginalized populations,” GLIDE said. “We remain committed to offering services that focus on stability, healing, reentry and empowerment.”

Speaking about collaborative courts, GLIDE said: “We have indeed seen greater efforts to divert individuals with substance use issues into treatment-focused programs rather than punitive systems.

“Programs like collaborative courts and pretrial diversion are important steps toward recognizing addiction as a health issue, not solely a criminal one.”

They explained that approaches such as collaborative courts align with evidence showing that pathways to recovery in the form of support and harm-reduction resources, as well as access to health care and social services, are more positively impactful than incarceration.

Another method the DA’s office and law enforcement have been using to crack down on crime is increasing surveillance in the city.

“We were a city that prioritized privacy over enforcement,” Jenkins said.

Jenkins said that, ironically, although much surveillance tech is created in San Francisco, it was not used by the city’s law enforcement until a public ballot measure passed in 2024 allowing the police to increase its surveillance methods.

Some of the surveillance tools now being used by police are license plate scanners to track stolen cars, increased filming of “troubled locations,” and drones for assisting police in tracking suspects after fleeing a scene.

Jenkins said they identify “troubled locations” using community feedback, aggregate data from prior arrests and 911 calls.

GLIDE said that although they recognize that surveillance tools with appropriate oversight can be used as public safety tools, “we are also mindful that increased surveillance technologies can sometimes have unintended consequences for already marginalized groups, particularly people of color, people experiencing homelessness, and individuals living with substance use disorder or mental health issues.

“It is critical that any use of surveillance tech comes with strong transparency, community input and strict protections to prevent misuse or over-policing of vulnerable communities. Trust between law enforcement and the communities they serve is vital, and any technology must support—not undermine—that trust.”

When it comes to the future of law enforcement in the city, Jenkins said: “We want to be fair. We want to have due process. We want to route people to the sources of help that they need appropriately. But we cannot abandon rules, and I think, to the extent that we continue to enforce rules, cities across our state in our country will be in better shape.”

The post How San Francisco Is Lowering Crime Rates appeared first on Newsweek.