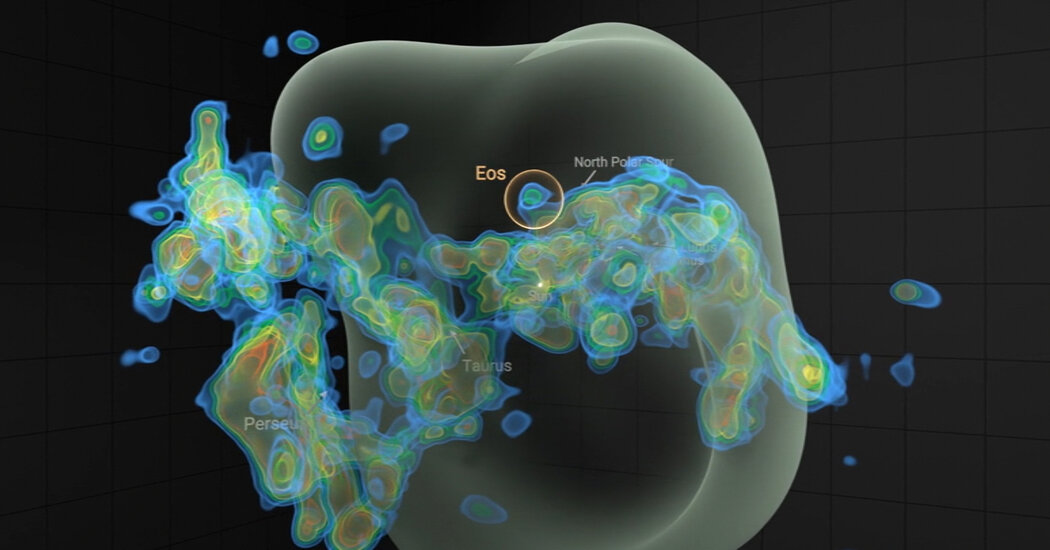

Stars and planets are born inside swirling clouds of cosmic gas and dust that are brimming with hydrogen and other molecular ingredients. On Monday, astronomers revealed the discovery of the closest known cloud to Earth, a colossal, crescent-shaped blob of star-forming potential.

Named Eos, after the Greek goddess of the dawn, the cloud was found lurking some 300 light-years from our solar system and is as wide as 40 of Earth’s moon lined up across the sky. According to Blakesley Burkhart, an astrophysicist at Rutgers University, it is the first molecular cloud to be detected using the fluorescent nature of hydrogen.

“If you were to see this cloud on the sky, it’s enormous,” said Dr. Burkhart, who announced the discovery with colleagues in the journal Nature Astronomy. And “it is literally glowing in the dark,” she added.

Identifying and studying clouds like Eos, particularly based on their hydrogen content, could reshape astronomers’ understanding of how much material in our galaxy is available to produce planets and stars. It will also help them measure the creation and destruction rates of the fuel that can drive such formations.

“We are, for the first time, seeing this previously hidden reservoir of hydrogen that can form stars,” said Thavisha Dharmawardena, an astronomer at New York University who is an author of the study. After Eos, she said, astronomers are “hoping to find many more” such hydrogen-heavy clouds.

Molecular hydrogen, which consists of two hydrogen atoms bound together, is the most abundant material in the universe. Stellar nurseries are chock-full of it. But it is difficult to detect the molecule from the ground because it glows in far-ultraviolet wavelengths that are readily absorbed by the Earth’s atmosphere.

Easier to spot is carbon monoxide, a molecule made up of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom. Carbon monoxide radiates light in longer wavelengths that can be detected by radio observatories on Earth’s surface, a more conventional technique for identifying star-forming clouds.

Eos, as immense as it is, evaded detection for so long because it contains so little carbon monoxide.

Dr. Burkhart noticed the cloud while studying data that was about 20 years old from the Far-Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrograph, or FIMS, an instrument aboard a Korean space satellite. She spotted a structure in the molecular hydrogen data in a region of space where she believed no molecular clouds were present, and then teamed up with Dr. Dharmawardena to investigate further.

“At this point, I had known pretty much all the molecular clouds by name,” Dr. Dharmawardena said. “This structure, I didn’t know at all. I couldn’t place it.”

Dr. Dharmawardena cross-checked the find with three-dimensional maps of the interstellar dust between stars in our galaxy. Those maps were built with data from the recently retired Gaia space telescope. Eos “was very clearly outlined and visible,” she said. “It’s this gorgeous structure.”

John Black, an astronomer at Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden who was not involved in the work, commended the technique used to reveal Eos.

“It’s really wonderful to be able to see the molecular hydrogen directly, to trace out the outlines of this cloud,” Dr. Black said. Compared with carbon monoxide, the hydrogen shows “a truer picture of the shape and size” of Eos, he added.

Using the molecular hydrogen content, the astronomers estimated the mass of Eos to be about 3,400 times that of our sun. That is much higher than the estimate computed from the amount of carbon monoxide present in the cloud — as little as 20 times the mass of our sun.

Similar measurements of carbon monoxide could very well be underestimating the mass of other molecular clouds, Dr. Burkhart said. That has important implications for star formation, she added, because bigger clouds form more massive stars.

A follow-up study of Eos, which has not yet been peer-reviewed, found that the cloud had not formed stars in the past. But the question remains whether it will begin to churn out stars in the future.

Dr. Burkhart is working with a team of astronomers to conceptualize a NASA spacecraft called Eos, which also inspired the name of the newly discovered cloud. The proposed space telescope would be able to map the molecular hydrogen content of clouds across the galaxy, including its namesake.

Perhaps such a mission would find more hidden clouds or revise knowledge about the ability of known stellar mists to coalesce their material into stars and planets.

“We don’t really know how stars and planets form,” Dr. Burkhart said. “If we’re able to look at molecular hydrogen directly, we’re able to tell how the birthplaces of stars are forming — and also how they’re being destroyed.”

Katrina Miller is a science reporter for The Times based in Chicago. She earned a Ph.D. in physics from the University of Chicago.

The post A Massive, Glow-in-the-Dark Cloud Lurking in Our Cosmic Backyard appeared first on New York Times.