When he was a 29-year-old on the Austin City Council, Greg Casar led a charge to repeal a ban on camping in the city so that homeless people would not rack up criminal records that could make it harder to find permanent housing.

Tent cities sprang up, conservatives protested and residents voted to reinstate the ban.

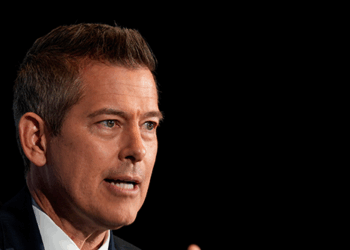

These days, Mr. Casar, 35, is the chairman of the House Progressive Caucus and a rising star in a Democratic Party struggling to find its footing during the second coming of President Trump. He has shifted his emphasis to respond.

“We can’t be known as the party of just the most vulnerable people,” Mr. Casar, the bilingual son of Mexican immigrants, said in a recent interview in an Uber en route to a town hall in Thornton, Colo. “This isn’t just about lifting up the poorest people, and that’s where the progressive movement has been.”

Mr. Casar’s goal now is winning back the working people who feel as though the Democratic Party is not for them anymore. He said that also means making economic matters, rather than cultural or identity issues, the party’s bread and butter.

“I’m shifting and changing,” he said. “On immigration, for example, in 2017, I would say, ‘Immigrant rights are human rights.’ I still believe that, but I’m now saying, ‘We need to make sure that all workers have equal rights.’ ”

He and his team refer to it as Resistance 2.0, and Mr. Casar took it out for a test drive last week. On a school stage here in this city north of Denver, more than 900 miles away from his district, he stood beside a cardboard cutout of a Republican lawmaker whose feet had been replaced with chicken claws.

The rest of the cutout’s body depicted Representative Gabe Evans of Colorado, a hard-right lawmaker elected in November who has held just one town hall since being sworn in. So here was Mr. Casar instead, hoping to show Democrats that their leaders were working to fill the void and defeat politicians too scared to show their faces in their districts amid a public backlash against Mr. Trump’s policies.

It was Mr. Casar’s third town hall in a Republican district, and he pushed back on the idea espoused by veteran party strategists like James Carville that Democrats should simply keep a low profile and “play dead,” letting Mr. Trump’s unpopular agenda win elections for them. If Democrats don’t make vast changes, he said, they will pave the way for a President JD Vance.

“A corpse is not an inspiring political leader,” Mr. Casar said at the town hall. “We need to be out there picking a villain and saying, ‘Elon Musk is stealing your Social Security money for himself.’”

Many attendees did not sound convinced that the Democratic Party was doing much inspiring at all. One after another, they lined up for questions and expressed general fear and pointed concern that the Democrats were not standing up to Mr. Trump in any real way. They demanded to know what, exactly, the plan was.

“I’d like some confidence that my Democratic votes are actually going to result in strengthening a system and protecting it,” Deb Bennett-Woods, a retired professor, told Mr. Casar.

“It’s frustrating when we feel like our Democrats — I’m sure they’re doing the work, but we don’t hear it,” another woman vented at the microphone.

As a young leader in his second term in Congress, Mr. Casar may be uniquely positioned to answer such angst. He is sprightly — in high school, he placed sixth at the Texas state championships in the mile and once ran a 4-minute, 17-second pace. Despite the anxiety of the current political moment, Mr. Casar presents as a sunny, happy warrior. And his roots are in the progressive populism of Senator Bernie Sanders, independent of Vermont, whom he endorsed early in the 2016 presidential campaign and introduced at Mr. Sanders’s first Texas rally of that campaign.

“Isn’t our party supposed to be working for the many against the few that are screwing them over?” Mr. Casar said in the interview.

Ahead of the town hall on Thursday, Mr. Casar popped up at a Hyatt in downtown Denver to meet with workers fighting their employer for an extra dollar an hour in pay that they said they were promised in their last contract negotiation.

“You deserve a raise,” Mr. Casar told them, first in English and then in Spanish. “I’m here with you in this. I’m not here asking for your vote. Your vote is your business, but what I want is to make sure that we all push for other politicians to be out here with you. Workers in this country deserve a big raise.”

He then accompanied them to hand-deliver a letter outlining the pay raise request to the head of human resources at the hotel, who looked uncomfortable and begged the group not to film her.

Standing with the workers, he said, was the most fun he’d had all day.

“It feels a lot more productive,” Mr. Casar said. “I prefer to do this than just voting ‘no.’ So often in Washington, we just get trapped in these senseless meetings.” (He likes to kick off his own caucus meetings by playing Marvin Gaye and Aretha Franklin, hoping to distinguish them from the tedium.)

Those workers, he noted in the car, may not have voted in past elections. Maybe this kind of outreach from a Democrat could change that in the next one.

Mr. Evans’ spokeswoman responded to Mr. Casar’s presence in Colorado’s Eighth District by calling him a “defund the police activist who wants to see socialism and transgenderism take over America.”

Mr. Casar rolled his eyes at that. But he said he had made a purposeful pivot to responding to the political crisis in which he finds himself and his party. It means fewer purity tests, and a bigger tent.

And it means allying himself with more moderate Democrats who represent competitive districts and emphasize their military backgrounds to get elected — the types who would never fight for urban camping rights for the homeless.

He is on a text chain with Representatives Pat Ryan of New York and Chris Deluzio in Pennsylvania, two Democrats representing swing districts who also want the party to focus on working people and make villains out of the billionaires benefiting from Mr. Trump’s policies.

“We’re just talking about issues that are central: utility bills, health care bills, housing affordability,” Mr. Ryan said in an interview. “We can rebuild a broad American and patriotic coalition.”

Mr. Ryan does not love the “Resistance 2.0” framing, but he and Mr. Casar share a vision for what the party needs to be about.

“If we’re resisting something, we’re resisting harm to our constituents, from a big corporation or a billionaire or a corrupt government official,” he said.

Mr. Casar concedes that he has made some mistakes since taking over the Progressive Caucus, a group of nearly 100 lawmakers that is one of the largest in the House. It was his idea for Democrats to hold up signs that read “Musk Steals” and “Save Medicaid” during Mr. Trump’s address to a joint session of Congress. The signs were widely panned, and Mr. Casar now admits they were a bit dopey.

“Looking back on it, I think that just showing up and then leaving would have been better,” he said. “We get pressured into acting like we never make a mistake. I learned that some of the things we pushed for in 2017 became too-easy targets, so we’ve got to change. And I learned from that speech that when the president is just going to lie through the speech, it’s probably best just to walk out.”

But he has been consistent since Election Day that economic populism is the right approach for his party.

After the election, when Democrats were bemoaning that incumbents worldwide lost because of inflation, Mr. Casar advised his colleagues to take a look at President Claudia Sheinbaum’s decisive victory in Mexico, where a representative of the incumbent party won on a populist economic agenda.

Since then, he has participated in a “Fighting Oligarchy” rally with Mr. Sanders and Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Democrat of New York. He sees himself as a team coach, and he refers to Ms. Ocasio-Cortez as “the No. 1 draft pick we’ve seen in my lifetime.”

Jetting around constantly can take a toll, especially on a young person attempting to have a normal life. He got dinged last year for skipping President Joseph R. Biden, Jr.’s address to House Democrats and going to a Joni Mitchell concert instead. It has also been tough at times on his partner.

“It’s really hard,” his wife, Asha, a philanthropic adviser, said of the realities of being married to an ambitious politician. “Greg is my favorite, but it’s not my favorite.”

He knows this, but Mr. Casar uses the word “resolute” to describe his commitment to the job and the fight ahead.

“There is a level of anxiety across the country that did not exist under Trump 1,” Mr. Sanders said in an interview, referring to Mr. Trump’s first term. “Greg understands that the future of American politics is to do what the Democratic leadership does not understand. That is to start addressing the serious crises of working families.”

Annie Karni is a congressional correspondent for The Times. She writes features and profiles, with a recent focus on House Republican leadership.

The post A Rising Democratic Star Pitches a ‘Resistance 2.0’ in the Age of Trump appeared first on New York Times.