If you have tips about DOGE and its data collection, you can contact Ian and Charlie on Signal at @ibogost.47 and @cwarzel.92.

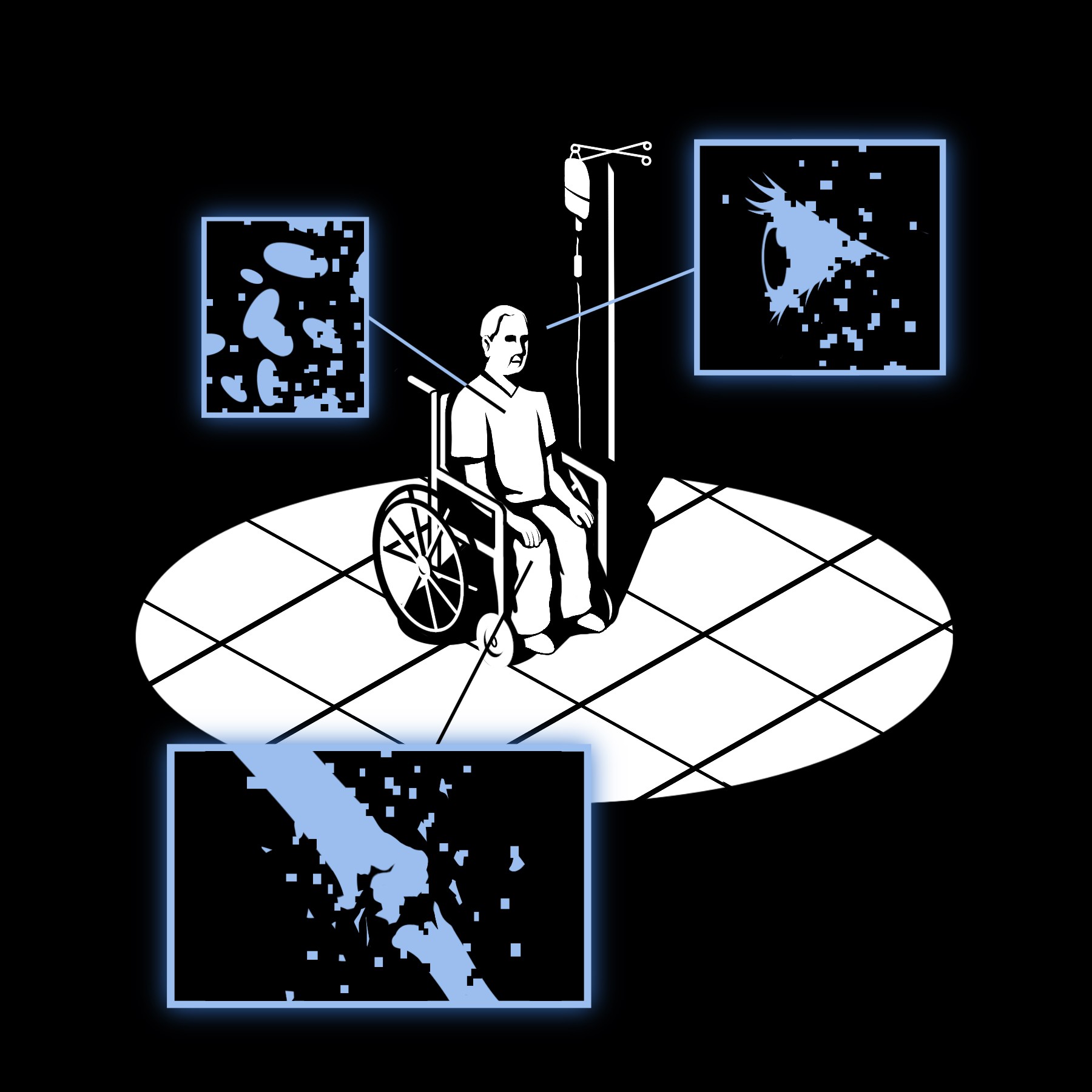

If you were tasked with building a panopticon, your design might look a lot like the information stores of the U.S. federal government—a collection of large, complex agencies, each making use of enormous volumes of data provided by or collected from citizens.

The federal government is a veritable cosmos of information, made up of constellations of databases: The IRS gathers comprehensive financial and employment information from every taxpayer; the Department of Labor maintains the National Farmworker Jobs Program (NFJP) system, which collects the personal information of many workers; the Department of Homeland Security amasses data about the movements of every person who travels by air commercially or crosses the nation’s borders; the Drug Enforcement Administration tracks license plates scanned on American roads. And that’s only a minuscule sampling. More obscure agencies, such as the recently gutted Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, keep records of corporate trade secrets, credit reports, mortgage information, and other sensitive data, including lists of people who have fallen on financial hardship.

A fragile combination of decades-old laws, norms, and jungly bureaucracy has so far prevented repositories such as these from assembling into a centralized American surveillance state. But that appears to be changing. Since Donald Trump’s second inauguration, Elon Musk and the Department of Government Efficiency have systematically gained access to sensitive data across the federal government, and in ways that people in several agencies have described to us as both dangerous and disturbing. Despite DOGE’s stated mission, little efficiency seems to have been achieved. Now a new phase of Trump’s project is under way: Not only are individual agencies being breached, but the information they hold is being pooled together. The question is Why? And what does the administration intend to do with it?

In March, President Trump issued an executive order aiming to eliminate the data silos that keep everything separate. Historically, much of the data collected by the government had been heavily compartmentalized and secured; even for those legally authorized to see sensitive data, requesting access for use by another government agency is typically a painful process that requires justifying what you need, why you need it, and proving that it is used for those purposes only. Not so under Trump.

This is a perilous moment. Rapid technological advances over the past two decades have made data shedding ubiquitous—whether it comes from the devices everyone carries or the platforms we use to communicate with the world. As a society, we produce unfathomable quantities of information, and that information is easier to collect than ever before.

The government has tons of it, some of which is obvious—names, addresses, and census data—and much of which may surprise you. Consider, say, a limited tattoo database, created in 2014 by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, and distributed to multiple institutions for the purpose of training software systems to recognize common tattoos associated with gangs and criminal organizations. The FBI has its own “Next Generation Identification” biometric and criminal-history database program; the agency also has a facial-recognition apparatus capable of matching people against more than 640 million photos—a database made up of driver’s license and passport photos, as well as mug shots. The Social Security Administration keeps a master earnings file, which contains the “individual earnings histories for each of the 350+ million Social Security numbers that have been assigned to workers.” Other government databases contain secret whistleblower data. At the Department of Veterans Affairs, you’ll find granular mental-health information on former service members, including notes from therapy sessions, details about medication, and accounts of substance abuse. Government agencies including the IRS, the FBI, DHS, and the Department of Defense have all purchased cellphone-location data, and possibly collected them too, via secretive groups such as the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. That means the government has at least some ability to map or re-create the past everyday movements of some American citizens. This is hardly even a cursory list of what is publicly known.

Advancements in artificial intelligence promise to turn this unwieldy mass of data and metadata into something easily searchable, politically weaponizable, and maybe even profitable. DOGE is reportedly attempting to build a “master database” of immigrant data to aid in deportations; NIH Director Jay Bhattacharya has floated the possibility of an autism registry (though the administration quickly walked it back). America already has all the technology it needs to build a draconian surveillance society—the conditions for such a dystopia have been falling into place slowly over time, waiting for the right authoritarian to come along and use it to crack down on American privacy and freedom.

But what can an American authoritarian, or his private-sector accomplices, do with all the government’s data, both alone and combined with data from the private sector? To answer this question, we spoke with former government officials who have spent time in these systems and who know what information these agencies collect and how it is stored.

To a person, these experts are alarmed about the possibilities for harm, graft, and abuse. Today, they argued, Trump is targeting law firms, but DOGE data could allow him to target individual Americans at scale. For instance, they described how the government, aside from providing benefits, is also a debt collector on all kinds of federal loans. Those who struggle to repay, they said, could be punished beyond what’s possible now, by having professional licenses revoked or having their wages or bank accounts frozen.

Musk has long dreamed of an “everything app” that would combine banking, shopping, communication, and all other human affairs. Such a project would entail holding and connecting all the information those activities produce. Even if Musk were to step back from DOGE, he or his agents may still possess data they collected or gained access to in the organization’s ongoing federal-data heist. (Musk did not respond to emailed questions about this, nor any others we posed for this story.)

These data could also allow the government or, should they be shared, its private-sector allies to target big swaths of the population based on a supposed attribute or trait. Maybe you have information from background checks or health studies that allows you to punish people who have seen a therapist for mental illness. Or to terminate certain public benefits to anybody who has ever shown income above a particular threshold, claiming that they obviously don’t need public benefits because they once made a high salary. A pool of government data is especially powerful when combined with private-sector data, such as extremely comprehensive mobile-phone geolocation data These actors could make inferences about actions, activities, or associates of almost anybody perceived as a government critic or dissident. These instances are hypothetical, but the government’s current use of combined data in service of deportations—and its refusal to offer credible evidence of wrongdoing for some of those deported—suggests that the administration is willing to use these data for its political aims.

Harrison Fields, a spokesperson for the White House, confirmed that DOGE is combining data that it has collected across agencies, but he did not respond to individual questions about which data it has or how it plans to safeguard citizens’ private information. “DOGE has been instrumental in enhancing data accuracy and streamlining internal processes across the federal government,” Fields told us in an emailed statement. “Through data sharing between agencies, departments are collaborating to identify fraud and prevent criminals from exploiting hardworking American taxpayers.”

For decades, government data have been both an asset and a liability, used and occasionally abused in service of its citizens or national security. Under Trump and DOGE, the proposition for the data’s use has been flipped. The sensitive and extensive collective store of information may still benefit some American citizens, but it is also being exploited to satisfy the whims and grievances of the president of the United States.

Trump and DOGE are not just undoing decades of privacy measures: They appear to be ignoring that they were ever written. Over and over, the federal experts we spoke with insisted that the very idea of connecting federal data is anathema. An employee in senior leadership at USAID told us that the systems operate on their own platforms with no interconnectivity by design. “There’s almost no data sharing between agencies,” said one former senior government technologist. That’s a good thing for privacy, but it makes it harder for agencies to work together for citizens’ benefit.

On occasions when sharing must happen, the Privacy Act of 1974 requires what’s called a Computer Matching Agreement, a written contract that establishes the terms of such sharing and to protect personal information in the process. A CMA is “a real pain in the ass,” according to the official, just one of the ways the government discourages information swapping as a default mode of operation. According to the USAID employee, workers in one agency do not and cannot even hold badges that grant them access to another agency—in part to prevent them from having access to an outside location where they might happen upon and exfiltrate information. So you can understand why someone with a stated mission to improve government efficiency might train their attention on centralizing government data—but you can also understand why there are rigorous rules that prevent that from happening. (The Privacy Act was passed to curtail abuses of power such as those exhibited in the Watergate and COINTELPRO scandals, in which the government conducted illegal surveillance against its citizens.)

The former technologist, who worked for the Biden administration, described a system he had tried to facilitate building at the General Services Administration that would provide agencies with income information in order to verify eligibility for various benefits, such as SNAP, Medicaid, and Pell Grants. A simple, basic service to verify income, available only to federal and state agencies that really needed it, seemed like it would be an easy success.

It never happened. (The former federal technologist blamed “enormous legal obstacles,” including the Privacy Act itself, policies at the Office of Management and Budget, and various court rulings.) The IRS even maintains an API—a way for computers to talk to one another—built to give the banking industry a way to verify someone’s income, for example to underwrite a mortgage application. But using that service inside the government—even though it was made by the federal government—was forbidden. The best option for agencies who wanted to do this was to ask citizens to prove their eligibility, or to pay a private vendor such as Equifax, which can leverage the full power of data brokering and other commercial means of acquiring information, to confirm it.

Even without regulatory hurdles, intermingling data may not be as straightforward as it seems. “Data isn’t what you’d imagine,” Erie Meyer, a founder of the U.S. Digital Service and the chief technologist for multiple agencies, including the CFPB, told us. “Sometimes it’s hard-paper information. It’s a mess.” Just because a federal agency holds certain information in documents, files, or records doesn’t mean that information is easily accessed, retrieved, or used. Your tax returns contain lots of information, including the charities to which you might have contributed and the companies that might have paid you as an employee or contractor. But in their normal state—as fields in the various schedules of your tax return, say—those data are not designed to be easily isolated and queried as if they were posts on social media.

An American surveillance society that fully stitched together the data the government already possesses would require officials to upend the existing rules, policies, and laws that protect sensitive information about Americans.

To this end, DOGE has strong-armed its way into federal agencies; intimidated, steamrolled, and fired many of their workers; entered their IT systems; and accessed some unknown quantity of the data they store. DOGE removes the safeguards that have protected controls for access, logs for activity, and of course the information itself. Borrowing language from IT management, the senior USAID employee called DOGE a kind of permission structure for privacy abuse.

But the federal technologist added something else: “We worship at the altar of tech.” Many Americans have at least a grudging respect for the private tech industry, which has changed the world, and quickly—a sharp contrast to the careful, if slow-moving, government. Booting out the bureaucrats in favor of technologists may look to some like liberation from mediocrity, even if it may lead to repression.

Musk has said that his goal with DOGE is to serve his country. He says he wants to “end the tyranny of bureaucracy.” But around Washington, people are asking one another what he really wants with all those data. Keys to the federal dataverse could, for example, be extremely useful to a highly ambitious man who is aggressively trying to win the AI race.

We already know that Musk’s people have access to large swaths of information from federal agencies—what we don’t know is what they’ve copied, exfiltrated, or otherwise taken with them. In theory, this material, whether usable together or not, could be recombined with other identifying information from private companies for all kinds of purposes. There has been speculation already that it could be fed into third-party large language models to train them or make the information more usable (Musk’s xAI has its own model, Grok); outside firms could use their own technologies to make sense of disparate sets of data, as well. Such approaches, the federal workers told us, could make it easier to turn previously obfuscated information, such as the individual elements of a tax return, into something to be mined.

Tech companies already collect as much information as possible not because they know exactly what it’s good for, but because they believe and assume—correctly—that it can provide value for them. They can and do use the data to target advertising, segment customers, perform customer-behavior analysis, carry out predictive analytics or forecasting, optimize resources or supply chains, assess security or fraud risk, make real-time business decisions and, these days, train AI models. The central concept of the so-called Big Data era is that data are an asset; they can be licensed, sold, and combined with other data for further use. In this sense, DOGE is the logical end point of the Big Data movement.

Collecting and then assembling data in the industrial way—just to have them in case they might be useful—would represent a huge and disturbing shift for the government. So much so that the federal workers we spoke with struggled even to make sense of the idea. They insisted that the government has always tried to serve the people rather than exploit them. And yet, this reversal matches the Trump transactional ethos perfectly—turning How can we serve our fellow Americans? into What’s in it for us?

Us, in this case, isn’t even the government, let alone your fellow Americans. It’s Trump’s business concerns; the private-sector ones that have supplicated to him; the interests of his friends and allies, including Musk, and other loyalists who enter their orbits. Once the laws, rules, and other safeguards that have prevented federal data from comingling fall away—and many of them already have in practice—previously firewalled federal data can be combined with private data sets, such as those held by Trump allies or associates, tech companies who want to get on the administration’s good side, or anyone else the administration can coerce.

Many Americans have felt resigned to the Big Data accrual of their information for years already. (Plenty of others simply don’t understand the scope of what they’ve given up, or don’t care.) Data breaches became banal—including at Equifax and even inside the government at the Office of Personnel Management. Some private firms, such as Palantir, already hold lucrative government data-intelligence contracts. As Wired recently reported, ICE cannot track “self-deportations” in near-real time—but Palantir can. Lisa Gordon, Palantir’s head of global communications, told us that the company does not “own, collect, sell or provide any data to our customers—government or commercial,” and that clients are ultimately in control of their information. However, she also added that Palantir “is accredited to secure a customer’s data to the highest standards of data privacy and classification.” Theoretically, even if federal data are stored by a third-party contractor, they are protected legally and contractually. But such guarantees might no longer matter if the government deems its own privacy laws irrelevant. Public data sets could become a gold mine if sold to private parties, though there is no evidence this is taking place.

The thought that the government would centralize or even give away citizen data for private use is scandalous. But it’s also, in a way, expected. The Vietnam War and Watergate gave Americans reasons to believe that the government can’t be trusted. The Cold War issued a constant, decades-long threat of annihilation and the necessary surveillance to avoid it. The War on Terror extended the logic into the 21st century. Optical, recording, and then computer technologies arose, offering new ways to watch the public. During the 2010s, Edward Snowden’s NSA surveillance leaks took place, and the Facebook–Cambridge Analytica scandal was brewing. By then, the 20th-century assumption that U.S. intelligence agencies were running mind-control experiments, infiltrating and disrupting civil-rights groups, or carrying out surreptitious missions at home like they do abroad had been fully internalized, and fused with the suspicion that Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Walmart were—in their own ways—following suit.

Earlier this month, The Washington Post reported that government agencies are combining data that are normally siloed so that identifying undocumented immigrants would be easier. At the Department of Labor, DOGE has gained access to sensitive data about immigrants and farmworkers, Wired reported. This and other reporting shows that DOGE seems to be particularly interested in finding ways to “cross-reference datasets and leverage access to sensitive SSA systems to effectively cut immigrants off from participating in the economy,” according to Wired.

A worst-case scenario is easy to imagine. Some of this information could be useful simply for blackmail—medical diagnoses and notes, federal taxes paid, cancellation of debt. In a kleptocracy, such data could be used against members of Congress and governors, or anyone disfavored by the state. Think of it as a domesticated, systemetized version of kompromat—like opposition research on steroids: Hey, Wisconsin is considering legislation that would be harmful to us. There are four legislators on the fence. Query the database; tell me what we’ve got on them.

Say you want to arrest or detain somebody—activists, journalists, anyone seen as a political enemy—even if just to intimidate them. An endless data set is an excellent way to find some retroactive justification. Meyer told us that the CFPB keeps detailed data on consumer complaints—which could also double as a fantastic list of the citizens already successfully targeted for scams, or people whose financial problems could help bad actors compromise them or recruit them for dirty work. Similarly, FTC, SEC, or CFPB data, which include subpoenaed trade secrets gathered during long investigations, could offer the ability for motivated actors to conduct insider trading at previously unthinkable scale. The world’s richest man may now have access to that information.

An authoritarian, surveillance-control state could be supercharged by mating exfiltrated, cleaned, and correlated government information with data from private stores, corporations who share their own data willingly or by force, data brokers, or other sources. What kind of actions could the government perform if it could combine, say, license plates seen at specific locations, airline passenger records, purchase histories from supermarket or drug-store loyalty cards, health-care patient records, DNS-lookup histories showing a person’s online activities, and tax-return data?

It could, for example, target for harassment people who deducted charitable contributions to the Palestine Children’s Relief Fund, drove or parked near mosques, and bought Halal-certified shampoos. It could intimidate citizens who reported income from Trump-antagonistic competitors or visited queer pornography websites. It could identify people who have traveled to Ukraine and also rely on prescription insulin, and then lean on insurance companies to deny their claims. These examples are all speculative and hypothetical, but they help demonstrate why Americans should care deeply about how the government intends to manage their private data.

A future, American version of the Chinese panopticon is not unimaginable, either: If the government could stop protests or dissent from happening in the first place by carrying out occasional crackdowns and arrests using available data, it could create a chilling effect. But even worse than a mirror of this particular flavor of authoritarianism is the possibility that it might never even need to be well built or accurate. These systems do not need to work properly to cause harm. Poorly combined data or hasty analysis by AI systems could upend the lives of people the government didn’t even mean to target.

“Americans are required to give lots of sensitive data to the government—like information about someone’s divorce to ensure child support is paid, or detailed records about their disability to receive Social Security Disability Insurance payments,” Sarah Esty, a former senior adviser for technology and delivery at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, told us. “They have done so based on faith that the government will protect that data, and confidence that only the people who are authorized and absolutely need the information to deliver the services will have access. If those safeguards are violated, even once, people will lose trust in the government, eroding its ability to run those services forever.” All of us have left huge, prominent data trails across the government and the private sector. Soon, and perhaps already, someone may pick up the scent.

The post American Panopticon appeared first on The Atlantic.