Photo by Kostiantyn Liberov/Libkos/Getty Images

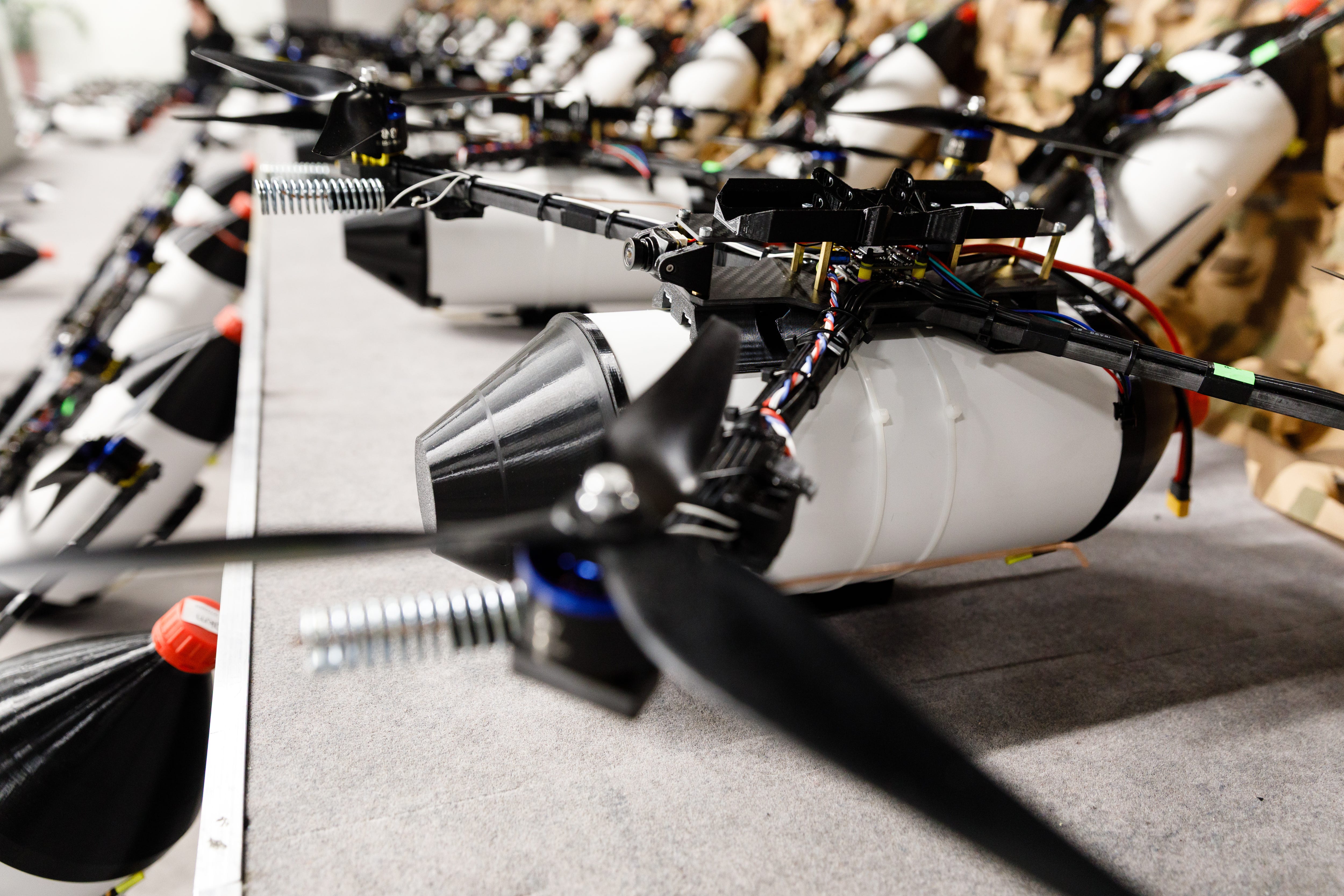

KYIV, Ukraine — Inside a nondescript high-rise in Kyiv, stacks of drone frames are piled on metal shelves, in cardboard boxes, and strewn across the floor. Nearby, young workers lean over their desks, turning the black, square-shaped frames into lethal weapons.

Down the hall are more rooms with more drones, hobby-style quadcopters not too much bigger than a human hand. They’ll soon be sent to Ukraine’s drone operators fighting to drive the Russians from their homeland in a new kind of war.

This assembly line, operated by 3DTech, is just one of hundreds of similar operations making Ukraine’s killer drones. They’re made with cheap parts, such as motors, cameras, and carbon-fiber frames, largely sourced from China, allowing Ukraine to build an arsenal on a budget. Companies like this one are on the ground floor of an industry that, within years, has grown into a juggernaut rivaling Russia’s own war machine. Kyiv has said it produced 2.2 million drones last year, compared to Moscow’s 1.5 million.

That industry has also become a model for the rest of the world in drone warfare. Business Insider traveled to Kyiv last month and interviewed drone company executives, troops, and other industry leaders to find out what countries can learn from Ukraine.

With Ukraine burning through thousands of combat drones each month, its drone makers are focused on rapid assembly and sourcing cheap parts. New firms are popping up in unusual spots like apartment complexes and basements as they race to meet demand. And to stay on the cutting edge of innovation, the manufacturers are fostering a new level of communication with troops in combat. Ukrainian soldiers have said that they routinely call or text manufacturers, leading to rapid iterative development, refinement, and, ultimately, better combat equipment.

Ukrainian companies are also developing drone ammunition, working on making parts domestically, and researching artificially intelligent systems that could power future drone swarms.

Photo by Kostiantyn Liberov/Libkos/Getty Images

Ukraine’s drone industry now aims to double production to 4.5 million aircraft this year. It’s funded largely by the country’s defense ministry — which since 2024 has spent more than $2.5 billion on uncrewed aerial systems — as well as Kyiv’s international partners, charity operations, crowdfunding efforts, and even individual military units.

“We’ve become the biggest drone manufacturer in the world, drones of tactical and strategic level,” Rustem Umerov, the Ukrainian defense minister, declared in February.

With defense tech booming, Ukraine’s drone makers aren’t just building weapons — they are rewriting the rules of modern warfare at a pace and scale that few could have imagined only a few years ago.

“This is especially prominent in the field of unmanned systems,” said Nataliia Kushnerska, a senior executive in Ukraine’s defense industry. “The invasion has brought immense tragedy and suffering for Ukrainian people, but it has also become a catalyst for rapid development of these technologies.”

‘We had to learn how to fight’

Ukraine has a long history of defense manufacturing. After the fall of the Soviet Union, Kyiv inherited a little less than a third of the empire’s arms industry. It had both production and research and development facilities, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, but it also had a problem.

The Soviet industrial base was highly integrated, meaning that Ukraine’s industries were suddenly fragmented and largely unable to produce complete systems and the accompanying ammunition. The post-Cold War political environment also placed less emphasis on military spending, and the number of arms-producing enterprises in the country dropped off over time.

Jake Epstein/Business Insider

Then, in 2014, Russia invaded Ukraine and military spending started to increase. At the time, the weapons procurement budget was $62 million; by 2021, it hit $836 million, SIPRI researchers wrote in February.

In 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion, sending forces across the border from multiple directions in a bid to capture Kyiv and topple the government. Spending on weapons and dual-use goods in turn surged to nearly $31 billion by 2023, SIPRI said. While a lot of that went to buying arms from abroad, the country’s defense industry was also growing.

Oleksandr Kamyshin, then-Ukraine’s minister of strategic industries, told BI last summer that Ukraine had long been a “peaceful” agricultural country.

Then, “they came and started killing us. We had to learn how to fight,” he said. “It was not our decision to switch from being a bread basket to being the arsenal.”

Kushnerska, the new chief executive of Brave1, a Ukrainian government incubator that funds defense industry innovation, said the full-scale invasion was a wake-up call.

The Ukrainians recognized that crippling Russia’s war machine, which enjoys manpower, machinery, and material advantages over Ukraine’s armed forces, required asymmetrical solutions. They also understood that self-sustainability is necessary; international partners are not always reliable.

Photo by Yevhenii Vasyliev/Global Images Ukraine via Getty Images

“From the start of the full-scale invasion, we understood that Ukraine cannot rely on available resources or international support alone — we needed to develop our own capabilities,” Kushnerska told BI.

Ukraine sought drones to level the playing field

Early in the conflict, Ukraine struggled with artillery shell shortages and the high cost of missiles and guided rounds, which typically cost hundreds of thousands of dollars apiece. Ukraine needed to generate mass firepower and needed to be able to do it cheaply.

That’s when uncrewed systems became a major focus area for the Ukrainian defense industry.

Ukrainian defense companies are now manufacturing all kinds of drones for combat missions. The most common are the small FPV drones that can fly into armored vehicles or troop positions and detonate or drop explosives from above. Typically, these are small quadcopters that companies like 3DTech have assembled and rigged with cable ties to carry warheads like RPGs that detonate on impact. One of 3DTech’s smaller FPV drones costs $220.

Ukraine is building other airborne drones, as well, including medium- and long-range assets, which Ukraine uses to execute strikes deep inside Russia, targeting its military and energy infrastructure. Kyiv also has reconnaissance and surveillance drones to spot the movements of Russian soldiers.

Serhiy Rakhmanin, a member of Ukraine’s parliamentary committee on national security, defense, and intelligence, told BI in Kyiv last month that “given the difficulty in obtaining or producing large quantities of missiles, Ukraine has focused on developing long-range drones, including drone-based missiles.”

AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka

“These drones are being used to strike targets inside Russia, impacting its military-industrial complex and front-line operations,” the lawmaker said through a translator. Zli Ptakhy is a Ukrainian company making fixed-wing “bomber” drones that can carry out strikes behind enemy lines.

Ukraine’s drone program isn’t only for producing a range of uncrewed aerial systems. The military fields several different types of naval drones that have been used in attacks on Russia’s Black Sea Fleet and ground robots for combat and logistics missions.

Drones vary in cost. Many smaller types cost as little as a few hundred dollars, while some of the bigger, more sophisticated versions can run for tens of thousands. Even on the high end, they’re still significantly cheaper than a cruise missile or tactical ballistic missile, which can cost millions.

The drones are eliminating warships, tanks, radar arrays, and advanced reconnaissance platforms, among other expensive combat assets. They’re also targeting bunkers with troops inside while sparing humans from dangerous missions.

“High-tech solutions like drones and robots became such game-changers,” Kushnerska said.

How Ukraine funded its drone development

The Ukrainian drone industry was born from crowdfunding efforts and start-ups, often civilians with software or engineering backgrounds. They were not connected to the military.

Photo by Alfons Cabrera/NurPhoto

The Ukrainian government recognized their potential, though, and supported projects through initiatives like United24’s Army of Drones or Brave 1, the latter of which was set up in 2023 to help companies get their technologies to the front.

The market is decentralized, and combat units are in direct contact with manufacturers. The Ukrainian government has given units a total of $60 million a month to buy drones and offered direct access to manufacturers.

“Private companies are the drivers of innovation, creating breakthrough technologies that change the situation on the battlefield and create a new defense tech market,” Kushnerska said.

The results are striking. At the start of the war, just a handful of Ukrainian companies were working on aerial drones. Now, there are over 500, with more than 1,100 individual products. Most of these products are registered with Brave1, which hosts testing events.

The planned procurement of 4.5 million drones this year is a massive increase over the roughly 2.2 million drones the war-torn country made in total last year.

Drone makers targeted innovations like electronic warfare

As the war has advanced, both sides have increasingly relied on electronic warfare, which renders weapons inoperable through signal jamming. At the start of the war, roughly 10 companies made electronic warfare devices. That figure has since swelled to nearly 150.

One such company is Rebel Group, which is working on a way to defend against unjammable fiber-optic drones, one of the latest innovations in drone warfare.

Mykhaylo Palinchak/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

Many drones rely on radio frequency connections between them and the operators, but these systems are vulnerable to signal jamming, flooding the control frequencies with noise.

Engineers must regularly shift their frequencies or use frequency-hopping software to reduce their exposure to noisy bandwidths. Both sides have adapted to this problem with drones that use fiber-optic cables to preserve a stable link; the drones are resistant to electronic warfare.

Rebel Group told BI at their office in Kyiv last month that fiber-optic drones have been increasingly used in combat over the past six months. It has given rise to an urgent need for better drone defenses.

Drones are ultimately faster, cheaper solutions for strong defenses

Ukraine’s drone-making industry and the broader arms business in Kyiv are different from those of many of the country’s NATO partners.

The US, for instance, often prioritizes larger and more expensive systems like fighter jets or armored vehicles, pursuing smaller quantities of exquisite systems rather than mass production through the acquisition of large quantities of cheap systems.

Kateryna Mykhalko, the director of Tech Force in UA, a coalition of Ukrainian weapons makers, said Western arms makers invest hundreds of millions of dollars in weapon systems that take years to make and may or may not work in real combat conditions.

“In Ukraine, it’s a totally different situation,” Mykhalko told BI at the Tech Force office in Kyiv. Ukraine’s drone makers invent their products within a few months or weeks; they quickly supply them to the military, test them in realistic situations, and adapt. At that point, they can receive investments for scaled production.

The process moves much faster, which has been essential for producing drones that meet battlefield needs at a scale able to match front-line demands.

Photo by Roman Chop/Global Images Ukraine via Getty Images

“When you have unlimited resources and you could have a lot of time, it’s easier” Mykhalko said. But she added that this type of situation “makes Ukraine really professional and efficient, and you could produce really cheap solutions which could provide strong national defenses.”

NATO allies are paying close attention to the drone fight, and some Ukrainians see this as a lucrative opportunity to sell their products abroad. Mykhalko said that Tech Forces advocates on behalf of private enterprises so they can operate internationally. But that is a difficult task because the government won’t allow it.

“We are trying to open controlled exports from Ukraine because the government budget is limited,” she said. Kyiv doesn’t have the money to procure all of the domestically produced drones.

What Ukraine lacks in size and resources compared to Russia, it is making up for with rapid innovation in its ever-expanding defense industry.

Kamyshin, the former minister of strategic industries, said last year that Ukraine will always have a smaller budget and fewer soldiers than Russia. This makes it critical for Kyiv to outperform its neighbor in the quality of its weapons and the people behind them.

“That’s the only way we can withstand,” he said.

The post Inside Ukraine’s drone boom: a blueprint for modern warfare on a budget appeared first on Business Insider.