Xi Jinping Boulevard runs a loop around Cambodia’s fast-growing capital, where signs in Chinese are rapidly overtaking those in English. The ring road around Phnom Penh, which was officially named after the Chinese leader last year, will soon connect to a Chinese-built airport that is being touted as one of the world’s 10 largest.

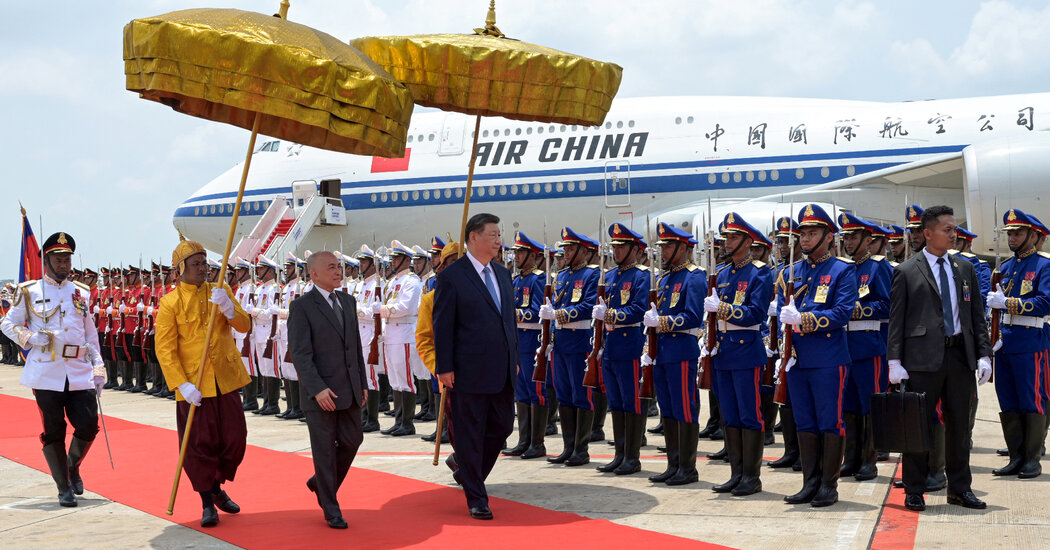

On Thursday, Mr. Xi, of boulevard renown, landed in Phnom Penh, where there are not one, but two, major thoroughfares named after Chinese Communist Party chiefs. (The other honors Mao Zedong.) Giant red banners greeted Mr. Xi, along with oversized portraits of him fronting new government ministries also built by China. Cambodians who had been paid $2.50 lined the streets, waving Chinese flags.

Mr. Xi’s state visit comes as the United States is threatening a walloping 49 percent tariff on Cambodian exports — like clothes for Nike and Lululemon — and abandoning dozens of aid projects here. Armed with airy promises of investment, Mr. Xi is underscoring with his Southeast Asia tour, which included stops in Vietnam and Malaysia, a clear geopolitical reality. In the superpower contest playing out in this part of the world, one contender is taking a big step ahead: China.

China is by far Cambodia’s largest trading partner and foreign investor, as it is for many other developing nations. Mr. Xi is pitching Beijing as these countries’ greatest champion, in implicit contrast with a United States that under President Trump seems intent on withdrawing from a position of global leadership.

“This is classic geopolitical theater, and Xi’s timing is no accident,” said Sophal Ear, a Cambodia-born political scientist at Arizona State University. “As the U.S. scales back its footprint in Cambodia, China steps in not just to fill the vacuum, but to showcase itself as the reliable and enduring partner.”

Mr. Xi’s charm offensive doesn’t mean that China enjoys broad popularity in the region. The Chinese leader arrived in Phnom Penh half a century to the day after the genocidal Khmer Rouge marched into the Cambodian capital and began an agrarian terror campaign supported by the Chinese Communist Party.

And Cambodia and other nations are desperate to negotiate down American tariffs to protect their export-led economies. A day before Mr. Xi’s arrival, Cambodian officials met online with Jamieson Greer, Mr. Trump’s top trade official, to try to protect the country’s 1 million garment workers from punishing duties. Prime Minister Hun Manet of Cambodia has already agreed to lower tariffs on American goods to 5 percent, from 35 percent.

Still, China’s economic heft has allowed Beijing access to markets and territory that would have been almost unthinkable a decade ago. Earlier this month, Cambodia formally unveiled a naval base refurbished by China, where Chinese warships have docked for months. The base ceremony was followed by joint military drills; naval exercises with the United States have been suspended since 2017.

The Cambodian government has denied that the facility, called Ream, is a de facto Chinese military outpost, part of what American strategists have termed “a string of pearls strategy” to seed Chinese military influence in key sea lanes. In an interview, Gen. Chhum Socheat, the deputy defense minister of Cambodia, said that the country’s leadership was happy to involve any nation willing to help with military upgrades.

“If the U.S. wants to support anything, we welcome that,” he said. “We welcome our friends without any discrimination.”

But Chinese construction at Ream, which began in 2022, was built on the razed remains of an American-built facility. U.S. defense documents shared with The New York Times showed that Cambodia had initially asked for and then ignored an offer by the United States to modernize Ream.

Cambodia’s cozy relationship with China was nurtured by Hun Sen, who was the world’s longest-serving prime minister before handing the reins to Mr. Hun Manet, his son, two years ago. In 1984, when Cambodia was still reeling from years of totalitarian terror, Mr. Hun Sen presided over a foreign ministry that decried China as the “mastermind” of the Khmer Rouge. (The radical Communist regime initially enjoyed support in part because the Cambodian countryside had been devastated by American bombardment spilling over from the Vietnam War.)

But as he tired of democratic checks to his power, like an independent judiciary and robust political opposition, Mr. Hun Sen lashed out at nations that tied their foreign aid to human rights. He accused American diplomats of trying to oust him and praised China as a constant friend. His son has continued the embrace, while obliterating any challenges to the Hun dynasty’s rule.

“The relationship between Cambodia and China has a long history and has grown to an inseparable level,” Mr. Hun Manet said last year when inaugurating Xi Jinping Boulevard. “This relationship is worthy of the values of mutual trust, especially political trust.”

Mr. Xi came to Phnom Penh with 37 vague “cooperative documents” in various economic fields, bringing hope after Chinese foreign investment in Cambodia nose-dived last year. He also expressed “strong support” for a canal that will allow China to directly ship goods to Cambodia, rather than go through Vietnam. Xi Jinping Boulevard runs to the site of the future canal.

Signaling political obedience, Cambodia reiterated that Taiwan is “an inalienable part” of China. Earlier this month, Cambodian authorities deported suspects in online fraud operations to China. Some were from Taiwan, which is a separately governed island.

In Malaysia the day before arriving in Cambodia, Mr. Xi witnessed the exchange of dozens of memorandums of understanding, all nonbinding and many amorphous. Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim of Malaysia has visited Beijing three times since taking power in late 2022. In a speech honoring Mr. Xi, Mr. Anwar presented his view of the state of the world.

“The rules-based order has been turned on its head, dialogue has yielded to demands, tariffs are imposed without restraint, and the language of cooperation is drowned beneath the noise of threats and coercion,” he said.

Mr. Anwar was not referring to China.

Ultimately, small countries like Cambodia need to maintain flexibility between superpowers, said Chea Thyrith, a spokesman for the ruling Cambodian People’s Party.

“With President Trump’s administration, we try to maintain a soft, respectful way of working together,” he said. “And with China, we are ironclad friends.”

In 2016, on a trip sponsored by the U.S. Embassy in Phnom Penh, Mr. Chea Thyrith observed the presidential contest between Mr. Trump and Hillary Clinton. He is now studying for a doctorate in international law at Beijing Foreign Studies University, which hosts students from more than 100 nations.

“It’s undeniable that in history U.S. aid helped the Cambodian people, and we pay gratitude for that,” Mr. Chea Thyrith said. “But now, without Chinese aid, more than 30 roads, bridges, airports, everything else, who helps Cambodia, who gives us aid without any strings attached?”

Back on Xi Jinping Boulevard, Soth Vanna, a teacher whose grandparents were killed by the Khmer Rouge, lamented how his family had not been given the promised compensation for farmland seized to build the new thoroughfare. Even as new malls, highways and condominiums transform Cambodia, farmers are being dispossessed. Activists and politicians who have campaigned for the landless have been beaten or jailed.

Still, Xi Jinping Boulevard brings Mr. Soth Vanna to his workplace fast. Roads bring development. There is a vast shopping center not far away, and a new flyover named for Mr. Hun Manet.

“China has given us a lot,” he said. “They’re building everything.”

Zunaira Saieed contributed reporting from Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Hannah Beech is a Times reporter based in Bangkok who has been covering Asia for more than 25 years. She focuses on in-depth and investigative stories.

The post How Does a Nation Charm China? Name a Boulevard After Xi Jinping. appeared first on New York Times.