It is 2016, and the City Council of Sausalito—a wealthy enclave on a hill overlooking Richardson Bay, north of San Francisco—is holding a public meeting about its plans to build a shelter for people experiencing homelessness. A man in a San Francisco Giants jacket gets up and voices his concerns about the shelter, which would have about 20 beds, and which the city is mandated to build under a 2007 California law. The man is worried about violence, crime, and the mental instability of the people who might be housed there—he mentions a recent murder in which a man killed his landlord and then killed himself in prison. As more people give comment, the general tenor is a mix of fear, ostensible compassion, and self-interest: There is a housing crisis, yes, but we shouldn’t have to do anything about it. “I’m very keen on homeless shelters,” one woman had said at a previous meeting. “I don’t have anything against people trying to get their lives together. I help people all the time trying to get their lives together. I have an issue with it at the schools and on my street—because I’m selfish.”

Then a man named Jeff stands up. Jeff is a member of a community called the “anchor-outs,” 100 or so people who live on boats off Sausalito’s shores. Jeff doesn’t consider himself homeless, but he knows he is part of the group that the man in the Giants jacket is concerned about. “I know, and you know, that Sausalito has no intention of building a homeless shelter in 2016,” Jeff says. “And yet we had to go through forty-five minutes of hate speech. I heard the homeless were responsible for murders—although it was somebody I guess killing his landlord, that means he had a place—sexual predators, thieves, mentally ill, etc. What this means is there is an attitude that needs adjustment. It’s the easiest thing in the world to do. It doesn’t take a dime.”

Jeff likely cares about the construction of a shelter, even though he is not homeless, because the same constituency that is resisting the shelter is also aiming to eliminate the anchor-outs. This is unfortunate, because the boats that the anchor-outs live on are, in a way, some of the last affordable housing in the area. One grand jury investigation found that to afford a one-bedroom apartment in Sausalito requires an income of $98,000 a year. With a housing market like that, who wouldn’t take to the water?

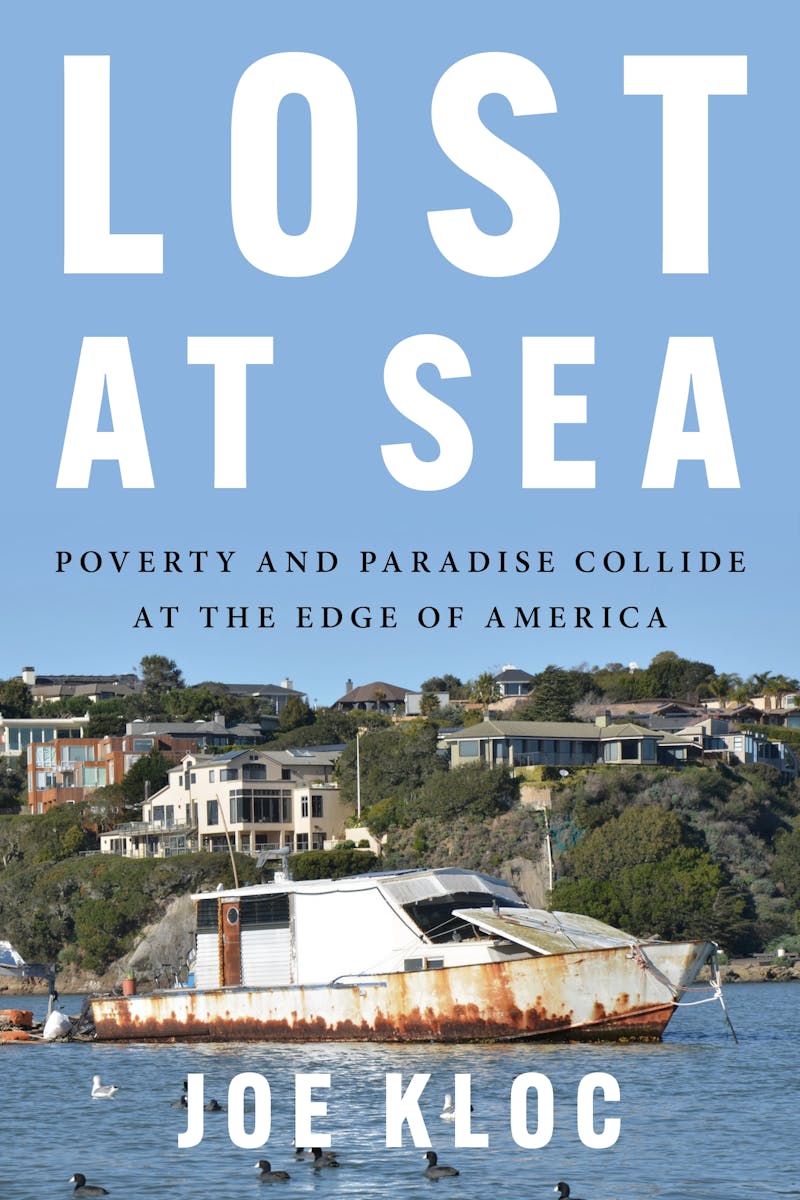

This story of Jeff and his fellow anchor-outs is captured in a new book, Lost at Sea: Poverty and Paradise at the Edge of America, by Joe Kloc. The book emerged from a 2019 essay that Kloc wrote for Harper’s Magazine (where he works as a senior editor) about the anchor-outs: their lives, their joys, and their struggles. The article was nominated for a National Magazine Award that year. The anchor-outs don’t fit our typical picture of homelessness in America, and many of the people Kloc talks to wouldn’t consider themselves homeless. Many seem to live on the water by choice—sometimes even as a rugged bohemian dalliance—but how much choice do they have in a hostile economic climate? The anchor-outs ride the definitional edge of homelessness: not quite homeless, not quite housed.

The book is a sensitive portrait of a surprising community on the brink of destruction. Like Andrew Ross’s Sunbelt Blues and Jessica Bruder’s Nomadland, it documents a new phase of the ongoing and escalating housing crisis: As people look for alternatives to unaffordable housing, new, fragile communities have sprung up or hung on, defying and nuancing our pictures of homelessness in America.

Richardson Bay is a natural harbor that on maps resembles a cartoon fish chomping into the Marin County peninsula. It is shallow, making it perfect as an anchorage. The bottom of the bay is covered with eelgrass, and its surface is covered with cormorants and seagulls. Around its edges sit the cities of Sausalito, Marin City, and Tiburon.

For thousands of years, the Coast Miwok lived in the area surrounding the bay, thriving off coastal fishing. As soon as Europeans arrived, and larger port cities like San Francisco developed at the end of the nineteenth century, Richardson Bay provided shelter for displaced and itinerant communities. During the 1849 Gold Rush, prospectors who came too late to find riches camped along the shores and lived in old boats. After the 1906 earthquake and a subsequent citywide fire devastated San Francisco, refugees once again settled in impromptu camps on Richardson Bay. The bay was a major shipyard during World War II for companies like Bechtel, which built and launched massive warships but abandoned their shorefront property as soon as the war was over. Returning troops settled in decommissioned boats and barges on shore, sometimes squatting for little or no rent. In the midcentury, artists, bohemians, and disaffected youths with drug habits took up residence in hundreds of houseboats and ramshackle huts. Among them were Shel Silverstein, Allen Ginsberg, and the British philosopher Alan Watts.

In the meantime, Sausalito had grown from a transportation hub with summer homes for wealthy San Franciscans and Victorians for British expats into a small city. As the surrounding terrain increased in value, the shoreline became contested, culminating in the “Houseboat Wars” of the late 1970s, in which residents of Sausalito attempted to clear the squatters and develop the shore into condominiums. In 1977, deputies brought in bulldozers to flatten a shipyard and build a parking lot, spraying protesters with a fire hose and running one over with a speedboat. The conflict was described by a local columnist as “almost a civil war.”

The wilder elements of the houseboats were tamed in time, and the squatters moved farther offshore. The federal government in 1969 had designated Richardson Bay as a special anchorage, essentially a free parking lot for sailors; in 1987, the region put a 72-hour limit on the anchorage, but it was scarcely enforced. A small community of anchor-outs settled the bay and lived rent-free on the water in something like a quiet truce with their landed neighbors.

The peace began to crack up in the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2008. As millions lost their homes to foreclosure and wages stalled in a recessionary funk, the anchorage filled with new residents, going from possibly 100 before the crisis to over 250 (by loose, unofficial counts). By 2015, “homelessness was transforming Sausalito, and a new, more aggressive stance toward the people of Richardson Bay was starting to take shape,” Kloc writes.

One day, while reporting on the anchor-outs in a park near shore, Kloc meets Jeff, the speaker at the City Council meeting, who tells him of the biblical Jubilee, in which debts are forgiven every 50 years. The jubilee, he believes, is a decade out. His comments are lucid and learned. Jeff is typical of the anchor-outs: articulate, eccentric, and, for the most part, elderly. Kloc then meets a man who goes by the name Innate Thought, a self-taught maritime lawyer whose boat had recently been raided by the Coast Guard and the local police. Exactly why he was raided and the details of his case are unclear, but he tells Kloc he plans to take it to the Supreme Court. The indeterminate nature of the story isn’t surprising: Truth and half-truth swirl together in this drifting community. Like Jeff, Innate is portrayed as sharp, if not a little odd—he uses a car battery on his boat to play a couple of hours of Grand Theft Auto V while listening to “Ave Maria” on repeat. In the photographs that accompany the Harper’s essay, Innate has the drawn and rough features of a barkeep in a Western.

Innate becomes Kloc’s guide, taking the reporter to his barge and introducing him to the nuances, ecstasies, and hardships of life at sea. The anchor-outs must row to shore to get groceries, propane, and cigarettes. Boats often must be repaired on the water. Storms drag their aquatic homes dangerously close to docks. Innate devotes his spare time to making a documentary about the anchorage, aided by footage collected by another anchor-out who, at 91, has been living in the bay for over 50 years. Some of the anchor-outs are close and visit with one another on their decks. Many of them are poetic souls, lovingly captured philosophizing over high-gravity beers on the shore or making paintings on driftwood.

While some of the residents of the anchorage are at sea seemingly by choice, many are not. “It’s really hard to live on a boat,” one woman tells Kloc. “But it feels a lot safer than being on San Francisco’s streets. It’s like a catch-22.” One anchor-out whom Kloc encounters works three jobs: a seasonal gig at Home Depot assembling grills, at the coffee shop Peet’s, and teaching chess on the side. Another resident says she was making $76,000 the year before she lost her job and her house. “I don’t want to be an anchor-out,” she tells Kloc. But it is the best of a lot of bad options.

In the course of Kloc’s reporting, the landed communities surrounding the anchorage begin to organize the expulsion of the anchor-outs. Law enforcement starts to declare dilapidated boats “marine debris,” and drags them away to be crushed. By 2018, the anchor-outs’ homes are disappearing at an alarming rate. Anchored-out residents fear arrest or detainment not for the time in jail, but because their homes might vanish in their absence. It’s hard to protest the watery demolitions because it’s not always clear who is doing the clearing, the Coast Guard or local authorities; Richardson Bay is overseen by a messy patchwork of agencies with differing jurisdictions. All the while, the unhoused population in surrounding Marin County explodes, with a 47 percent increase in just a few years. In the same period, the anchorage grows by about 20 percent. And still the city of Sausalito fails to comply with the state of California mandate to build a homeless shelter.

In 2020, the pandemic sweeps over the county, and boats stop disappearing as frequently. A major storm in 2021 destroys numerous boats and forces some of the anchor-outs to establish an encampment on shore. The camp is too close to the yacht club, so the city relocates them to a site possibly contaminated with toxic waste. Then enforcement ramps up again. A population of over 200 boats dwindles to 60 or less by 2024. The anchorage may be in its last days.

The city of Sausalito wants to rid itself of irregularly housed people, and will likely be somewhat successful in doing so. It is not alone. One hundred and fifty cities across 32 states have passed laws to outlaw camping and allow the bulldozing of tent cities. The camping bans, legalized in the wake of a Supreme Court decision in June 2024, effectively criminalize homelessness. They have proliferated in large metropolises like Austin, Texas, and in small cities like Elmira, New York, which has gone so far as to ban people from sleeping in cars. Fremont, California, recently banned camping by threatening a $1,000 fine and six months of jail time for sleeping outside and even tried to criminalize anyone “aiding and abetting” those living out of doors. Such actions do nothing to solve the underlying factors that caused the anchorage to grow to over 200 boats or a tent city to expand overnight in the middle of a wealthy town. They do not address low wages and expensive rents, nor short-term shelter needs. They simply wish the problem away. “Disappearance, through force or trickery, is often the objective of policies aimed at unhoused communities,” Kloc writes.

Kloc’s book adds to what is now almost a genre of volumes that give distinction to the story of the housing crisis by documenting people who are not completely homeless (in a crude imagining of the term) but are certainly irregularly housed. The anchor-outs are in a similar position to families and individuals living in extended-stay motels, who rose to national consciousness in 2011 with a 60 Minutes piece on the hellish conditions in a motel off Route 192 near Disney World in Florida: broken lights, cockroaches, sweltering rooms, kids playing near a bustling drug trade. This story was fictionalized in director Sean Baker’s 2017 movie, The Florida Project, and covered in depth in Sunbelt Blues: The Failure of American Housing (2021) by Andrew Ross. The book documents families who lost everything in the Great Recession and moved into motels to survive. Many motel residents were gainfully employed but still unable to save two or three months’ rent in order to make a deposit on a permanent home. One family lived in a one-bedroom suite for three years.

Jessica Bruder’s Nomadland (which came out in 2017 and was adapted into an Oscar-winning feature film in 2020) follows vagabonds and retirees living out of their vehicles as they travel to grueling gigs picking sugar beets in North Dakota or packing merchandise at Amazon warehouses in Nevada. Bruder introduces us to Linda May, a 64-year-old woman who, in the wake of the Great Recession, takes to the road with her dog to work seasonal jobs. As Bruder follows May, she finds a whole community of people like her, many of whom had lost their homes to foreclosure. When she comes upon a group of elderly people living in campers, Bruder muses, “Sometimes I felt like I was wandering around post-recession refugee camps.”

The same could be said of the anchor-outs in Sausalito, and it is not surprising that May resembles Kloc’s main guide, Innate Thought. Both are wise and rootless, sometimes struggling to make meaning of life, given their circumstances. The Walmart parking lot, where RVers like May could once stay for free, is akin to the special anchorage of Richardson Bay, essentially a giant aquatic parking lot. And while Bruder’s characters largely bristle at being called homeless, like the anchor-outs, many admit they came to their current arrangement more out of necessity than by choice. “We were presented with this lifestyle as being exciting and innovative and it is,” one of them writes on her blog. “However the truth of the matter is most of us are doing this because of our financial situation.”

All of these books show people trying to make the best of a bad situation, but who are powerless to change the social and economic factors that govern their lives. The books’ characters have checked out of the system that demands they work full-time (or overtime) to pay rent or mortgage, because they want to but also because they have to. They do not have the savings to get a rental apartment or house. They cannot make a better job appear just by grinding a couple of extra side-hustles.

A maddening aspect of Lost at Sea is that it is a narrative in which everything and nothing happens. There are few distinct climaxes, and characters rarely go through major transformations. Boats disappear, and often neither Kloc nor the anchor-outs know exactly why; the mystery would be difficult to solve, and no one seems motivated to figure it out. At one point, a man’s body floats up to the docks, and we never learn who he was or what might have happened to him. The book has no single antagonist. Kloc intentionally doesn’t name the City Council members, who float in and out of a story that spans almost a decade as faceless people in suits. The anchor-outs themselves can’t agree on a villain, vaguely blaming the “Hill People” for their troubles. Even the establishment of definite protagonists is a slippery business: The anchor-outs are an ever-shifting cast of characters. Innate, ostensibly the book’s main character, leaves the anchorage halfway through the book, after receiving a surprise inheritance and moving to Arizona. Kloc cannot necessarily be faulted for these factors—they are true of housing stories everywhere.

The housing crisis has a narrative problem, which is that it never ends.

The housing crisis has a narrative problem, which is that it never ends. Camps are cleared only to reappear elsewhere; a story of people housed is followed by a report that overall homelessness grows; tenants organize against a greedy landlord, and their fight drags on for years unresolved. Unhoused people have to go somewhere, and they will likely end up in a tent city under a highway, on federal land, doubled up with family, living in vans, or perhaps incarcerated. The anchorage was one of many obscure respites for those fleeing the unaffordability of American life. The frustrating features of Kloc’s book reflect the amorphous, unsatisfying way that the housing crisis continues to pathetically roll on.

The real reason for the crisis, and the explosion of people living at anchor in Richardson Bay, in motels in Florida, and on the road, are low wages and high rents. Kloc could possibly have gone deeper into that context for the anchor-outs’ lives, but to really delve into those twin features of our economy would have been a completely different book. Such narrative complications might be an excuse to simply not tell these stories at all, and surely numerous enterprising journalists hunting for the next optionable feature for Hollywood will turn away from the messiness of these tales. Luckily, Kloc did engage, giving us a human portrait of an impromptu community of people trying to survive.

While the mass of people unable to afford to live like mainstream America swells, mainstream America is now hell-bent on eliminating their irregular housing. Sausalito has destroyed the anchor-outs’ community, scattering the refugees to the wind. Today there are an estimated 30 boats at anchor. Under new laws, the anchorage must be cleared out completely by 2026. Communities vanish, but the people who make up those communities do not disappear. The anchor-outs will have to lay their heads somewhere. The story, unfortunately, continues.

The post The Last Days of the Boat-Dwellers of Sausalito appeared first on New Republic.