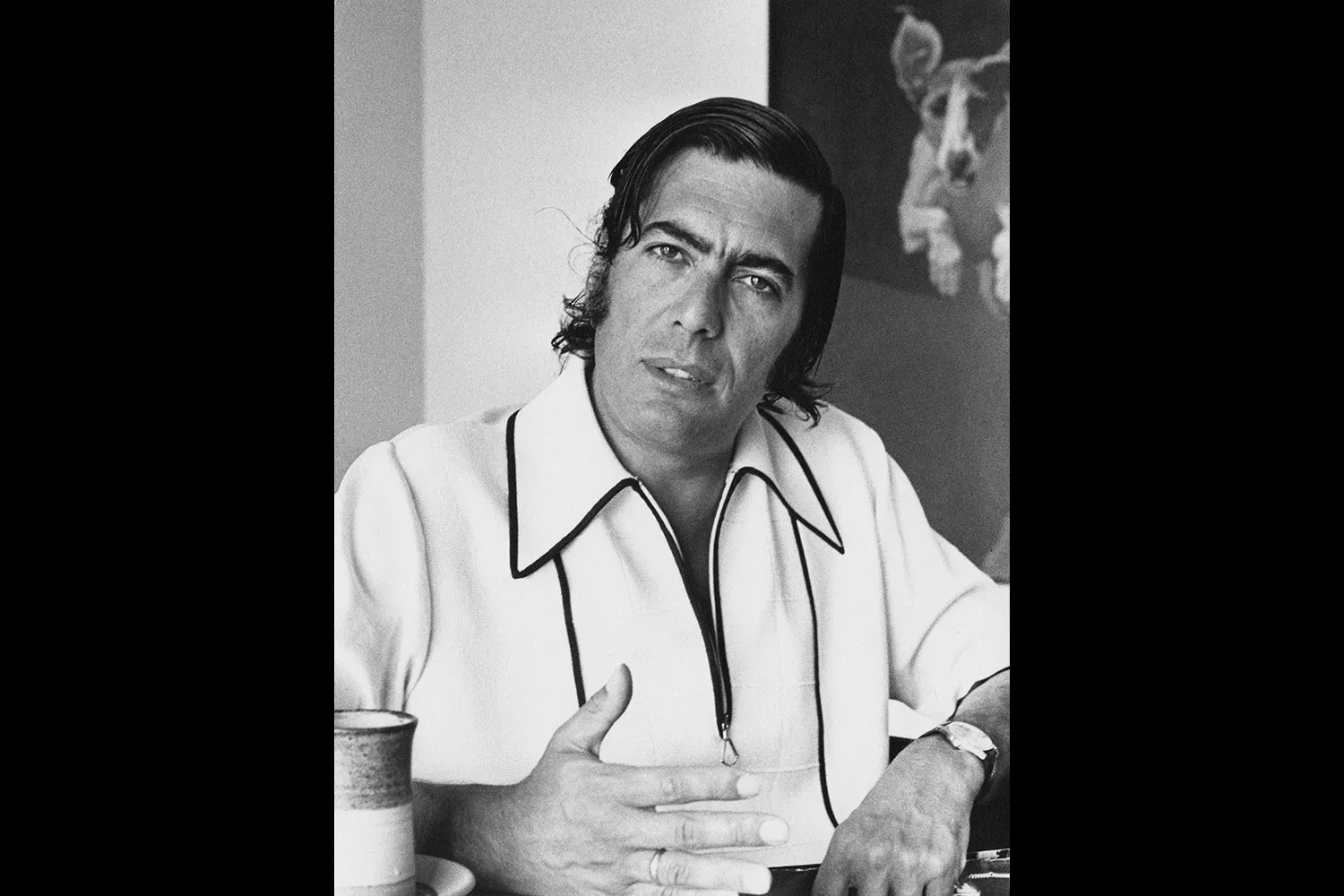

In his acceptance speech for the 2010 Nobel Prize in literature, Mario Vargas Llosa, who died on April 13 at the age of 89, noted that he learned from French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre that “words are acts”—that writing about the politics of the present and the opportunities to shift direction can, in Vargas Llosa’s words, “change the course of history.”

Vargas Llosa’s literature, fueled by a passionate commitment to individual liberty, aimed to do just that.

The author of more than 50 books over a span of six decades, Vargas Llosa was a household name in Latin America. He will be remembered as a staunch defender of liberalism and the free market—indeed, that may be his enduring mark on history—yet in his youth he was animated by leftist ideology, discovering then what he called his first “utopian illusion”: communism.

Vargas Llosa had demons to fight then: a violent, authoritarian father and the gross inequities he saw around him during the right-wing dictatorship of Gen. Manuel Odría. As a teenager, Vargas Llosa read Out of the Night, the bestselling 1940 autobiographic novel by German writer Richard Julius Hermann Krebs, and was struck by the author’s idealism and courage as a militant communist resisting the Nazis.

While attending the National University of San Marcos in Lima, Vargas Llosa decided to live out those ideals by joining Cahuide, a communist student group. He was a member of Cahuide for only a year, but his admiration for socialist ideology did not quickly wane, nor did his interest in Peru’s social and political injustices. His experiences as a young boy living in the northern city of Piura, and later as a teenager sent to the Leoncio Prado Military Academy by his abusive father, served as inspiration for his early works.

Vargas Llosa’s first book of stories, The Leaders, was published in 1959 when he was just 23. The tales in the collection are infused with memories of what he called the “tender violence” he witnessed while still in school in Piura. He explored the imposition of power and the struggle against authority through his stories of boys standing up to a domineering school director.

It was his 1963 novel, The Time of the Hero, that launched Vargas Llosa’s international career. The novel’s unflinching exploration of class, racism, and exclusion, told through the lives of cadets at Leoncio Prado, caused outrage among Peru’s military elite. In an official ceremony on an outdoor patio, the school burned a thousand copies of the book. The bonfire did not deter Vargas Llosa, who followed with other novels denouncing Peru’s social order, including The Green House (1966) and Conversation in the Cathedral (1969).

The Time of the Hero, translated into more than a dozen languages, is also considered by some as a launch point for the Latin American Boom, the most important Spanish-language literature movement of the 20th century.

The writers of this movement—authors such as Julio Cortázar, Gabriel García Márquez, Carlos Fuentes, José Donoso, and Vargas Llosa himself—were experimental, highly political, and broadly popular. This marked the first time that contemporary Latin American writers, promoted by the Spanish publishing house Seix Barral and its literary agent Carmen Balcells, found a wide international audience. (Jorge Luis Borges was not part of the movement, but his international popularity grew as a result of it.) Before his death, Vargas Llosa was the last living member of the movement.

The Latin American Boom lasted from the beginning of the 1960s to the late 1970s and was greatly influenced by both the triumphs and failures of the Cuban revolution. The movement’s own rise and fall paralleled Cuba’s struggles and the broader contest between the two reigning ideologies of the age, socialism and capitalism.

Like his fellow authors in the movement, as well as many other intellectuals and artists around the globe, Vargas Llosa initially admired the Cuban revolution. He first visited Cuba in 1962 as a journalist working for the French broadcaster RTF and became captivated by what he considered a “generous, libertarian, and profoundly democratic revolution.” He grew close to Fidel Castro’s regime through Casa de las Américas, a Cuban cultural organization that promoted left-wing Latin American authors by sponsoring annual literary prizes and holding conferences in Havana.

Vargas Llosa gradually became disillusioned with the regime, however. His first disappointment occurred in the mid-1960s, when he learned that Cuba was holding dissidents, common criminals, and sexual minorities in agricultural forced labor camps. This prompted Vargas Llosa to write a private letter to Castro expressing his dismay, telling him: “Commander, I really don’t understand. This does not fit with my vision of Cuba.”

Castro’s support of the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 spurred the novelist to publicly criticize the Cuban regime. In an article titled “Socialism and the Tanks,” published in the Peruvian magazine Caretas, he said the decision was “a dishonor for Lenin’s homeland, a political stupidity of dizzying proportions, and an irreparable blow to the cause of socialism in the world.”

By this time, Vargas Llosa was living in England, teaching at Queen Mary University of London. As detailed in his collection of essays The Call of the Tribe (2018), he had become a voracious reader of the works of liberal thinkers such as Karl Popper, Isaiah Berlin, Friedrich Hayek, and Adam Smith, which intensified his anxieties about his leftist leanings.

Vargas Llosa’s socialist convictions dissolved further in 1971, prompted by the arrest of Heberto Padilla, one of Cuba’s leading poets. In an open letter published in Le Monde, Vargas Llosa and many other Latin American and European writers argued that “the use of repressive measures against intellectuals and writers who have exercised the right of criticism within the revolution can only have deeply negative repercussions among the anti-imperialist forces of the entire world.” Castro responded by accusing them of working for the CIA, and Padilla did the same after his release a month later.

This was a crucial moment in Vargas Llosa’s political and literary life and marked his final shift away from socialism and toward liberalism. The break cost him personal relationships—most famously with Colombian novelist and essayist Gabriel García Márquez, whom Vargas Llosa would eventually call Castro’s “lackey”—but Vargas Llosa regained what he called a “freedom that I did not know I had lost.” In defense of the revolution, he had unwittingly suppressed his true opinions, and he vowed never to do so again.

During the 1970s, Vargas Llosa dedicated himself fully to his writing, living with his family in Barcelona and Lima and publishing humorous novels including Captain Pantoja and the Special Service (1973)—a satire about a brothel created for a military unit in the jungle—and Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter (1977), based on his scandalous first marriage to Julia Urquidi, his uncle’s sister-in-law. Shortly afterward came the widely acclaimed The War of the End of the World (1981), which American literary critic Harold Bloom included in what he called his “Western canon.”

In 1983, Peruvian President Fernando Belaunde Terry invited Vargas Llosa to lead an investigation into the assassination of eight journalists in the town of Uchuraccay, Peru. The Shining Path, a Maoist-Leninist terrorist organization, was waging a brutal war against the Peruvian government at the time, and the investigation found the journalists had been murdered by local villagers who had mistaken them for Shining Path members.

A few years later, political violence was still raging in Peru, and then-President Alan García’s experiments with heterodox economics were causing rampant hyperinflation and economic recession. Vargas Llosa had returned briefly to Britain in 1986 and had become an admirer of then-Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and her economic policies. García’s attempts to nationalize the banking sector prompted Vargas Llosa to found a right-wing political party, Freedom Movement, and to organize protest marches in 1987—decisions that launched the writer directly into the political fray.

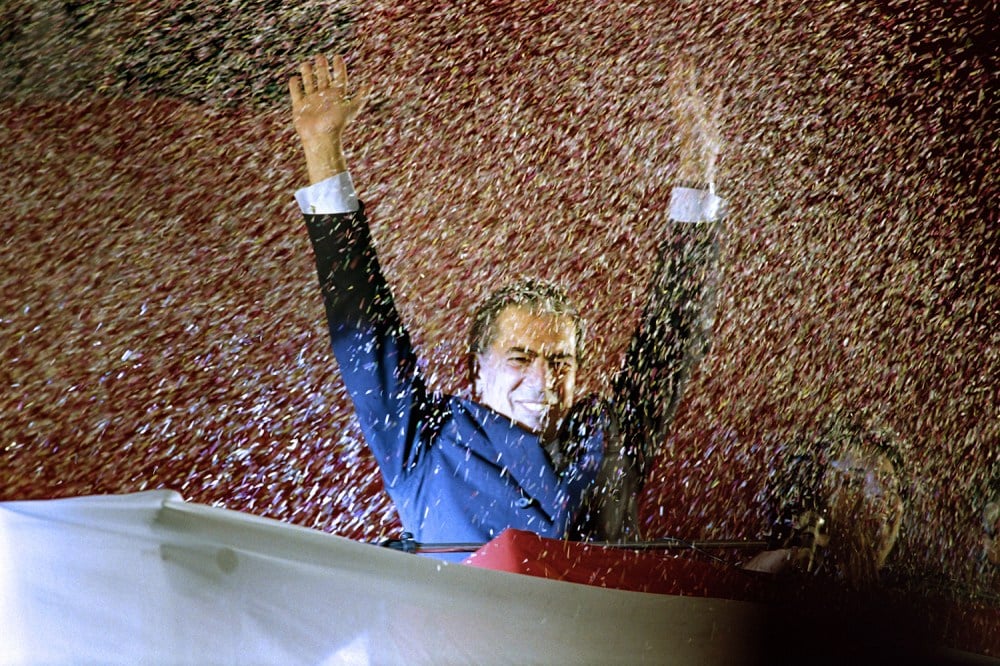

Vargas Llosa went on to run for president in 1990 under the center-right coalition Democratic Front, proposing liberal economic policies such as privatization and liberalization as the solution to Peru’s economic crisis. Studying liberalism and later witnessing Thatcher’s government had convinced him that capitalism and liberal democracy were superior moral and economic systems and that liberal democracy was the only system under which a diversity of people could peacefully coexist.

Despite a strong campaign, Vargas Llosa lost to Alberto Fujimori, an engineer and newcomer who went on to implement a highly corrupt autocracy. (Fujimori died last year at the age of 86.) After this defeat, Vargas Llosa withdrew from active politics but remained attuned to Peruvian affairs despite moving to Spain and taking Spanish citizenship. His writing turned again to the depravity of authoritarianism, particularly in The Feast of the Goat (2000), based on Rafael Trujillo’s cruel and despotic rule in the Dominican Republic from 1930 to 1961.

Then, in 2010, a half-century into Vargas Llosa’s literary career, the Swedish Academy awarded him the Nobel Prize in literature “for his cartography of structures of power and his trenchant images of the individual’s resistance, revolt, and defeat.”

Toward the end of his life, Vargas Llosa was optimistic about Latin America’s future, saying that he and the region had undergone the same ideological evolution. Ironically, although the author had long been a fervent defender of democratic causes in Latin America, by this point he seemed mainly concerned with opposing the left.

In Peru’s 2021 presidential election, for instance, Vargas Llosa supported Keiko Fujimori (the eldest daughter of his old adversary Alberto Fujimori) and her false allegations of fraud against left-wing rival Pedro Castillo. That stance provoked dismay among many Peruvians who felt Vargas Llosa was betraying his long-held democratic ideals.

For his part, Vargas Llosa maintained that Fujimori, who ultimately lost the election, was the “lesser of two evils.” The writer was determined to stay true to the values of liberalism and freedom he had regained after leaving communism behind, no matter the cost.

The post Mario Vargas Llosa: A Literary Colossus Who Aimed to Change the World appeared first on Foreign Policy.