Coffee prices have spiked significantly over the past four years as bad weather reduced production. Add in rising tariffs on coffee-producing countries like Brazil and Colombia, and that cup of joe is looking more and more like a morning luxury.

But there’s a newly published technique designed to make your coffee grounds go further – courtesy of a slightly overexcited group of physicists and fluid mechanics experts at the University of Pennsylvania.

About a year ago, staff in Arnold Mathijssen’s lab started pondering how to extract the most coffee using the fewest beans as they hung out at their lab’s coffee table. They’ve just published their findings.

Titled “Pour-over coffee: Mixing by a water jet impinging on a granular bed with avalanche dynamics,” their 10-page paper in the journal Physics of Fluids was published Tuesday.

Fluid mechanics and maximizing coffee extraction

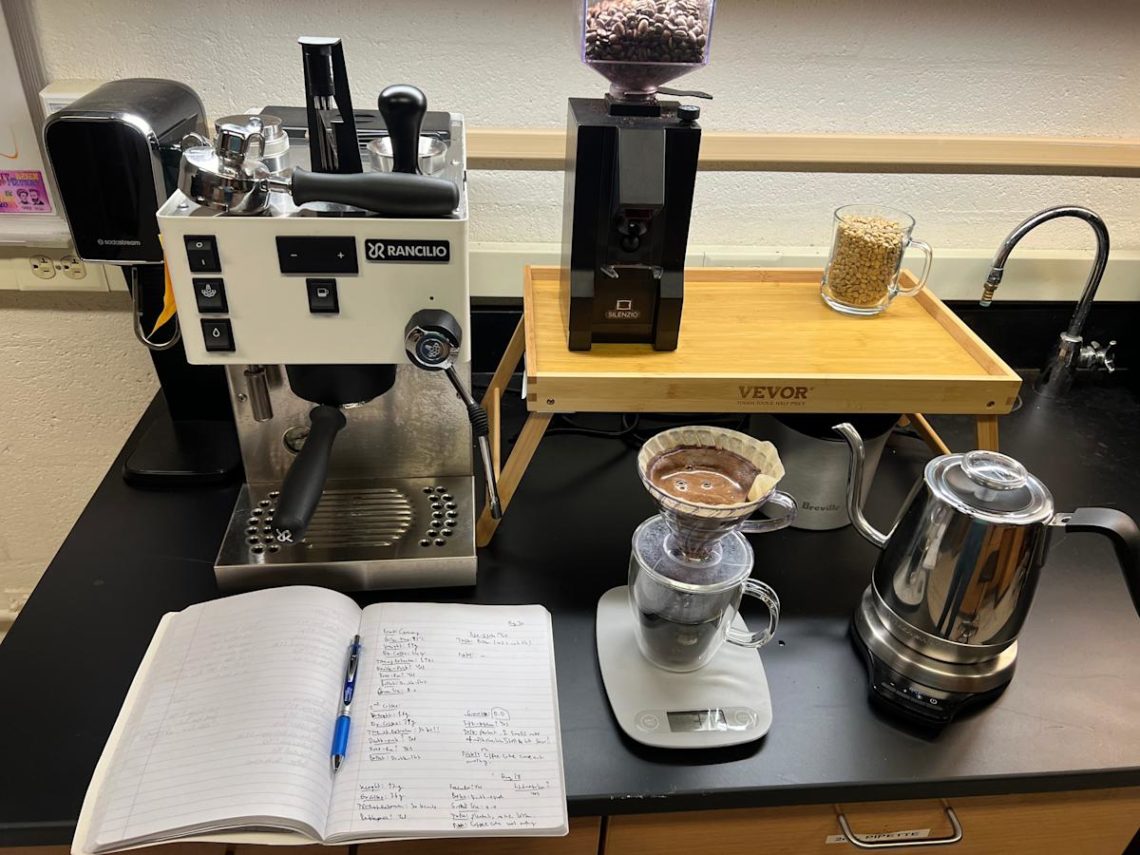

“It began around our coffee station, which is basically a space on one of our lab benches,” said Mathijssen, a professor of physics at the university.

One of his Ph.D. students, Ernest Park, is “the main coffee enthusiast in the lab,” Mathijssen said. The lab’s coffee-making apparatuses include an espresso machine, a French press and a pour-over setup. “But pour-over is the drink Ernest really loves,” he said.

A bunch of fluid mechanics experts, a lab full of equipment and a whole lot of caffeine: What could go wrong?

Or in this instance: “What could go right?”

Experimenting at the coffee station

Park initially began simply trying out different methods of pouring the boiling water in his pour-over coffee. As any self-respecting science lab does, the group had a logbook at the coffee station to record data about what made the best coffee.

“Initially he was just trying out different things, pouring coffee from different heights and such. Then he said: ‘Wait. This tastes good, but we need to do the actual experiments,” Mathijssen said.

They moved the effort to another lab bench and began experimenting with pour height and water stream size, but they realized they needed better data to determine exactly what was happening in the coffee filter.

“We couldn’t really prove what the mechanism was,” Mathijssen said.

Coffee grounds being opaque – and a fluid mechanics lab being a fluid mechanics lab – the effort quickly ramped up.

Soon they had assembled a quantity of small silica gel particles about the size of coffee grounds, a see-through pour-over filter, a laser sheet to illuminate the setup from the side, and a high-speed camera to allow them to film and analyze the images using some custom-made Python and Matlab computer code.

It’s all about the coffee ground avalanche

After doing dozens of experiments and analyzing the results, Park, Mathijssen and lab member Margot Young came up with a definitive technique to extract the maximum amount of coffee from the fewest number of beans.

In science terms, they were studying “the hydrodynamics of pour-over coffees, especially how a liquid jet interacts with a granular bed of submerged coffee grounds.”

In layman’s terms, they have this advice:

-

Pour the boiling water over the ground coffee slowly so the water has more time to be in contact with the grounds. The longer the pour time, the greater the extraction.

-

But don’t pour too slowly, because that can result in the water not fully mixing with the coffee grounds, resulting in some of the coffee being under-extracted and some over-extracted.

-

Increase the pour height to increase the velocity of the water. This helps create an “avalanche” in the coffee grounds that causes them to be maximally exposed to the boiling water.

-

Ensure that the water pours as a stream rather than breaking into droplets. If you pour too slowly or go too high, the stream breaks and the avalanche stops. You want to maintain a smooth, laminar flow of water hitting the coffee.

-

A thin jet of water – most easy produced from a gooseneck kettle – was the easiest way to get a slow, laminar pour. It’s possible to get a thin jet from a regular kettle but harder to do.

A slow, laminar pour (meaning a single stream of water and not droplets) resulted in the most flavorful coffee, the scientists determined. But the final part of the experiment was to test the actual amount of coffee solids extracted by analyzing the dissolved compounds.

This was done by making cups of coffee using various pouring heights and stream sizes, evaporating the coffee in an oven and then weighing the dissolved solids.

Does this add to science’s body of coffee knowledge?

Admittedly, most of Mathijssen’s research is more esoteric than this. Recent papers include “Collective intercellular communication through ultra-fast hydrodynamic trigger waves” and “Enhancement of bacterial rheotaxis in non-Newtonian fluids.”

The coffee research came about in part because during COVID-19, when their lab was shut down, the team began a food science initiative “because it meant we could do some experiments at home,” Mathijssen said.

That resulted in papers such as “Culinary fluid mechanics and other currents in food science,” published in 2023. They have since begun outreach to local schools to do kitchen science seminars to raise student interest in physics.

For the coffee experiments, a literature review showed there had already been research into the fluid mechanics of the liquids involved in espresso machines and French press coffeemakers.

“But as far as we know,” Mathijssen said, “there’s nothing yet on pour-over coffee.”

Until now.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: How to make the perfect pour-over coffee, according to science

The post Scientists release instructions for how to make a perfect cup of coffee appeared first on USA TODAY.