It is rare that we can watch the unfolding of a global economic downturn with such precision as we can today. With a 145 percent U.S. tariff on China and a 125 percent retaliatory levy by Beijing, the world’s largest bilateral trading relationship is effectively frozen. We have not even begun to see the consequences and knock-on effects, from the coming U.S. inflation shock to a potential reversal of China’s purchases of U.S. Treasury bonds. Other countries have gotten a 90-day reprieve after new U.S. rates as high as 50 percent briefly went into effect, but the threat of a worldwide convulsion remains. With every day that businesses and investors in the United States and elsewhere cannot plan their purchases and investments—or trust that Washington won’t flip-flop again—the cogs of the global economy move slower and slower.

How quickly things can spiral down became clear after U.S. President Donald Trump announced steep new tariffs on almost all U.S. imports on April 2. Trillions of dollars were wiped off the financial markets in a matter of days. As investors began to pull money out of the U.S. dollar and U.S. bonds, signals of financial contagion began flashing red. With neither Trump nor Chinese President Xi Jinping showing any inclination to back down, the risk of their confrontation metastasizing into a global economic conflagration is high.

U.S. economic history has a lot to say about how trade wars can set off something much, much worse. Since the beginning of the 19th century, the United States has suffered six economic depressions—which I define as six or more quarters of sustained economic contraction, although there is no standard definition. All but one were either directly caused or significantly worsened by tariffs and trade embargoes. As a historian who studies international trade, global commodities, and financial panics, I can assure you that Trump’s tariff policies will be devastating unless someone manages to stand up to him and make it stop.

One of the most powerful forces in economic life is comparative advantage, the benefit provided by international trade that allows a country to specialize based on its natural advantages in growing wheat, weaving cloth, or coding software. By trading these goods internationally, each country can allocate scarce resources to the things that its farmers, miners, and manufacturers can most cheaply produce. In theory, everyone benefits from international trade.

The theory has been borne out. When a continent-wide potato famine forced the United Kingdom and other European states to introduce free trade in food in 1846 it led to a shocking increase in prosperity that few expected. Some previously protected groups were hurt; European landowners grumbled that Russia and the United States benefited most. This was because the fertile plains of Russian-controlled Ukraine and the U.S. Midwest produced wheat so cheaply that the price of farmland dropped in Europe. It also led the rural poor in Britain and Europe to leave for the city, setting off a wave of urbanization and industrialization.

Of course, a large and well-endowed country or common market—like China, the United States, and the European Union—can put a thumb on the scales of free trade by jiggering exchange rates to favor exports generally or providing subsidies to push particular kinds of trade their way: corn over wheat, computer chips over textiles, textiles over rice. Environmental and labor regulations also tip the scales, often in unexpected ways. Monopolists in large countries often favor regulations, including tariffs, that shield against competition and multiply the value of their scarce assets.

As a former British colony, the United States has always been particularly vulnerable to tariff wars. For centuries, Britain molded its colonies’ trade to the motherland’s purpose. The colonies of New York, Maryland, and South Carolina were expected to provide flour and rice for the slave-powered tobacco and sugar plantations in Virginia and the Caribbean. Britain prohibited the colonies from manufacturing their own textiles, iron, and paper. The increasing limitations Britain imposed on the colonies’ international trade finally led to the American Revolution. From its start, the Articles of Confederation and then the Constitution sought to limit executive action that would sharply or rapidly change international trade. Revenue bills were lodged in the House, the Senate was required to approve them, and the executive remained limited to the power of the veto.

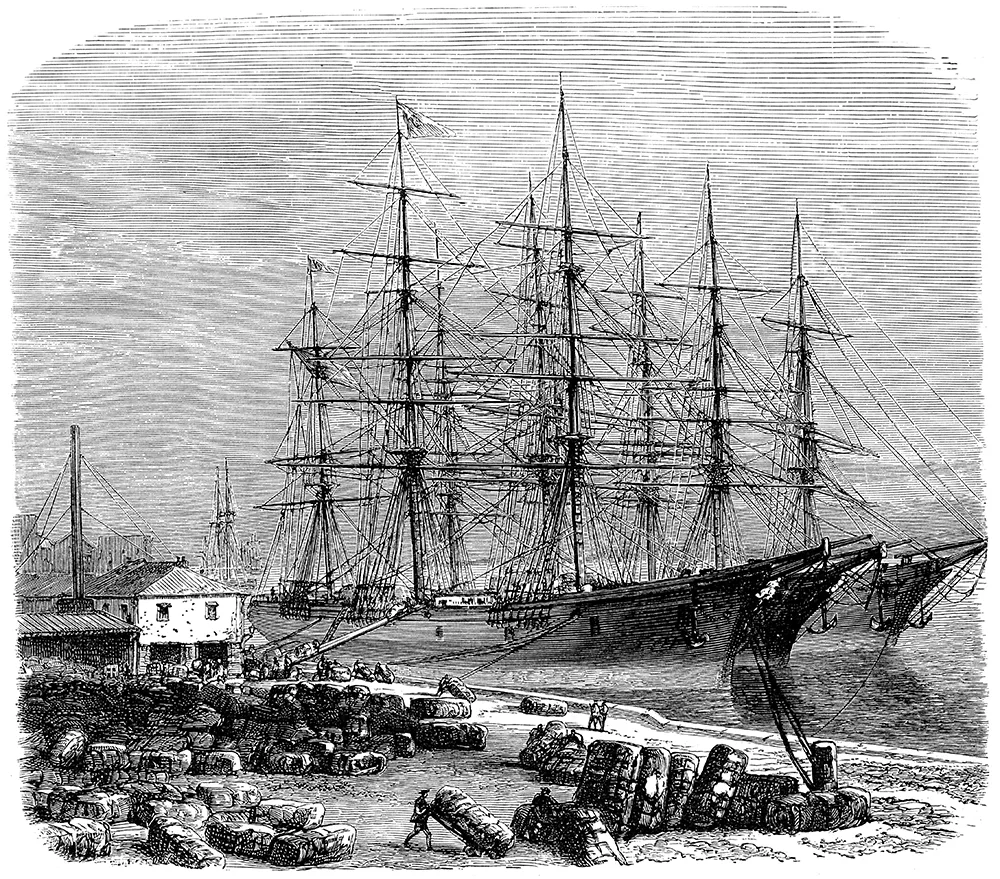

America’s first depression had its origin in 1816 when Britain—having just won a world war against Napoleon—dumped vast quantities of woolen fabric originally contracted to clothe European soldiers and sailors. It was Britain’s first Army-Navy surplus sale. American merchants and wool manufacturers balked at the sudden arrival of cheap woolen fabric and urged Congress to pass, in March 1817, the Navigation Acts, which blocked British ships and their cheap goods. Britain retaliated in May with orders-in-council that effectively blocked U.S. ships from delivering grain to Britain’s Caribbean colonies. U.S. farmers lost the Caribbean markets they had dominated for more than a century. By December 1818, U.S. wheat prices dropped 50 percent, and farmers could no longer pay the mortgages on their land owed to the U.S. Land Office. Farmers’ debts to country stores went unpaid, and so did country stores’ debts to furnishing merchants in U.S. cities.

The Panic of 1819 had begun, and the trade restrictions continued to distort markets. Over time, New York rescued itself by smuggling wheat across the Great Lakes to Canada, where Toronto and Montreal millers turned it into bonded British flour for sale in the Caribbean. Virginia, Georgia, and South Carolina only prospered by shifting from wheat and rice to slave-based cotton production. Within a decade, the Anglo-American trade war had made the cost of feeding Caribbean plantations so high that slaveholders there pressed the mother country to abolish slavery—but not before reimbursing them for their slaves. International trade restrictions first passed in 1817 stifled U.S. grain exports, which further entrenched cotton production—and with it, slavery—in the U.S. South.

Hasty executive action in international trade by President Andrew Jackson started the next American depression. Since the depression of 1819, long, snaking credit chains had funded the expansion of cotton plantations in the U.S. South. The Second Bank of the United States, together with seven British banks called the Seven Sisters, borrowed from British investors and issued bills of exchange that provided credit to smaller, regional U.S. banks, which then gave short-term loans to slave traders in the Upper South, who bought enslaved people in Virginia and South Carolina and sold them to cotton plantations in Georgia, Mississippi, and Louisiana. Because interest rates were set by the Bank of England, a small increase in the rate in London could make it impossible for slaveholders to buy land or slaves in New Orleans.

Jackson, persuaded that the Second Bank and the Seven Sisters were plotting against him, passed a series of executive orders in 1834 and 1836 designed to break the slaveholders’ dependence on British credit. One order removed deposits from the Second Bank of the United States, transferring them to a series of favored banks connected to Jackson’s political allies. Another order prohibited farmers from borrowing from banks to pay their mortgages to the U.S. Land Office, forcing them to use gold, the currency at the time. This benefited Southern slaveholders with gold mines in northern Georgia and western North Carolina (this was before gold was discovered in California), but the sudden demand for gold greatly exceeded supply.

The Bank of England, seeing its own gold disappearing into the United States, raised the bank rate and briefly cut the Seven Sisters off from international exchange. Thus began the depression of 1837. Southern planters absconded from their debts, abandoned plantations, and carried their slaves to the independent Republic of Texas where they were safe from creditors. Stores folded. Manufacturers failed. Within five years, seven states failed to pay bonds they had issued internationally.

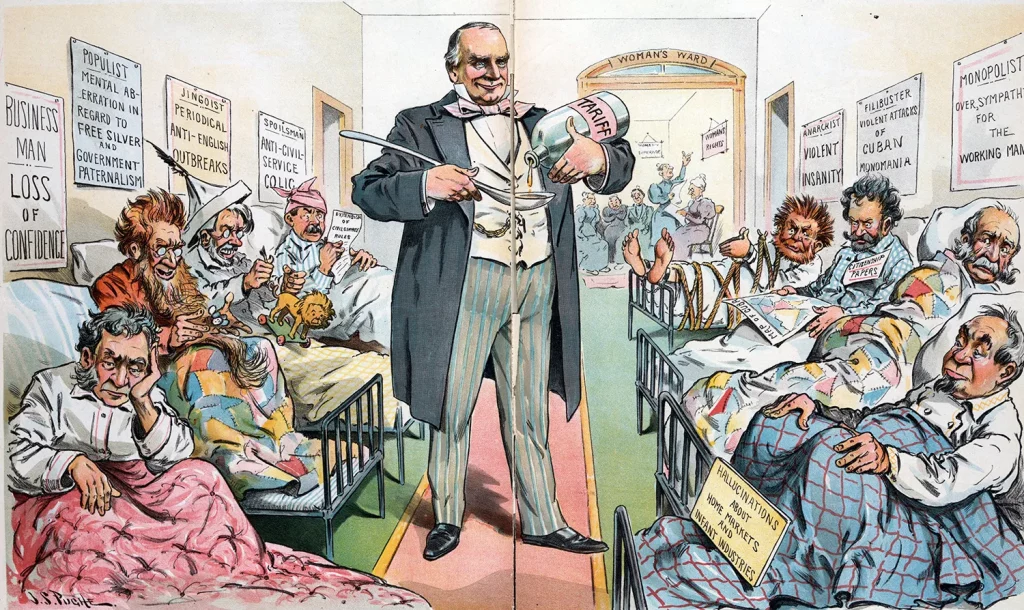

The next depression, in 1873, followed drastic shifts in international commodity prices, but no hasty action on tariffs caused it. But that cannot be said for the depression of 1893. In 1890, the House of Representatives revised its rules for legislating, making Congress surprisingly efficient and powerful. Feeling their oats, Republicans passed the McKinley Tariff Act of 1890, which raised tariffs on manufactured imports from 38 to 50 percent while eliminating the tariff on semi-refined sugar—a huge difference item for a country that exported canned foods like peaches, salmon, and beef, all of which used sugar as a preservative at the time. Steep tariffs, however, had the effect of drastically reducing U.S. revenue, as they often do. Within two years, this nearly drained the U.S. Treasury of gold, which led foreign lenders to sell off U.S. bonds, particularly those issued by railroad companies. Debtors feared that without gold in the Treasury, Washington would abandon the gold standard, and that bonds would be paid off in depreciated U.S. currency.

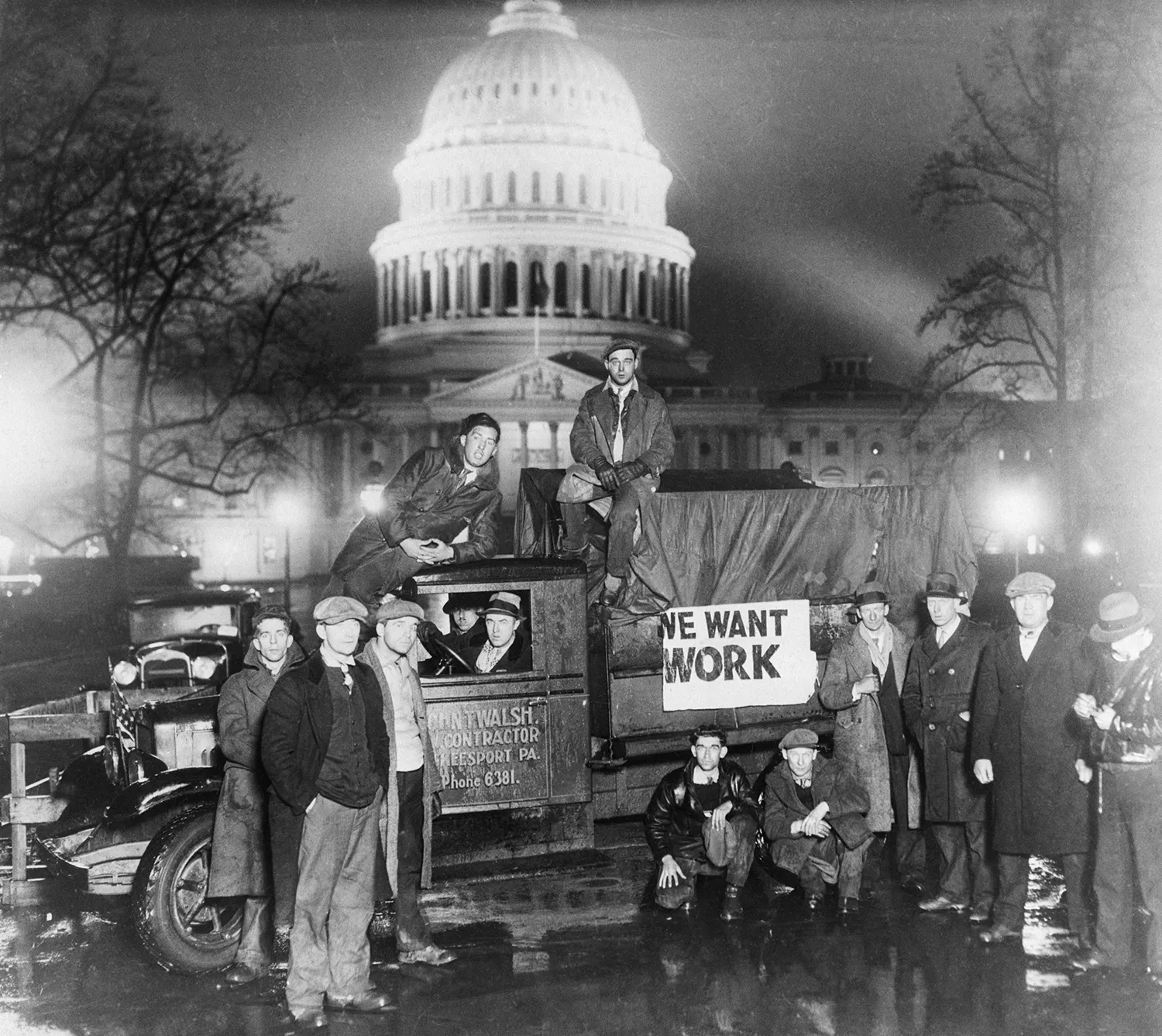

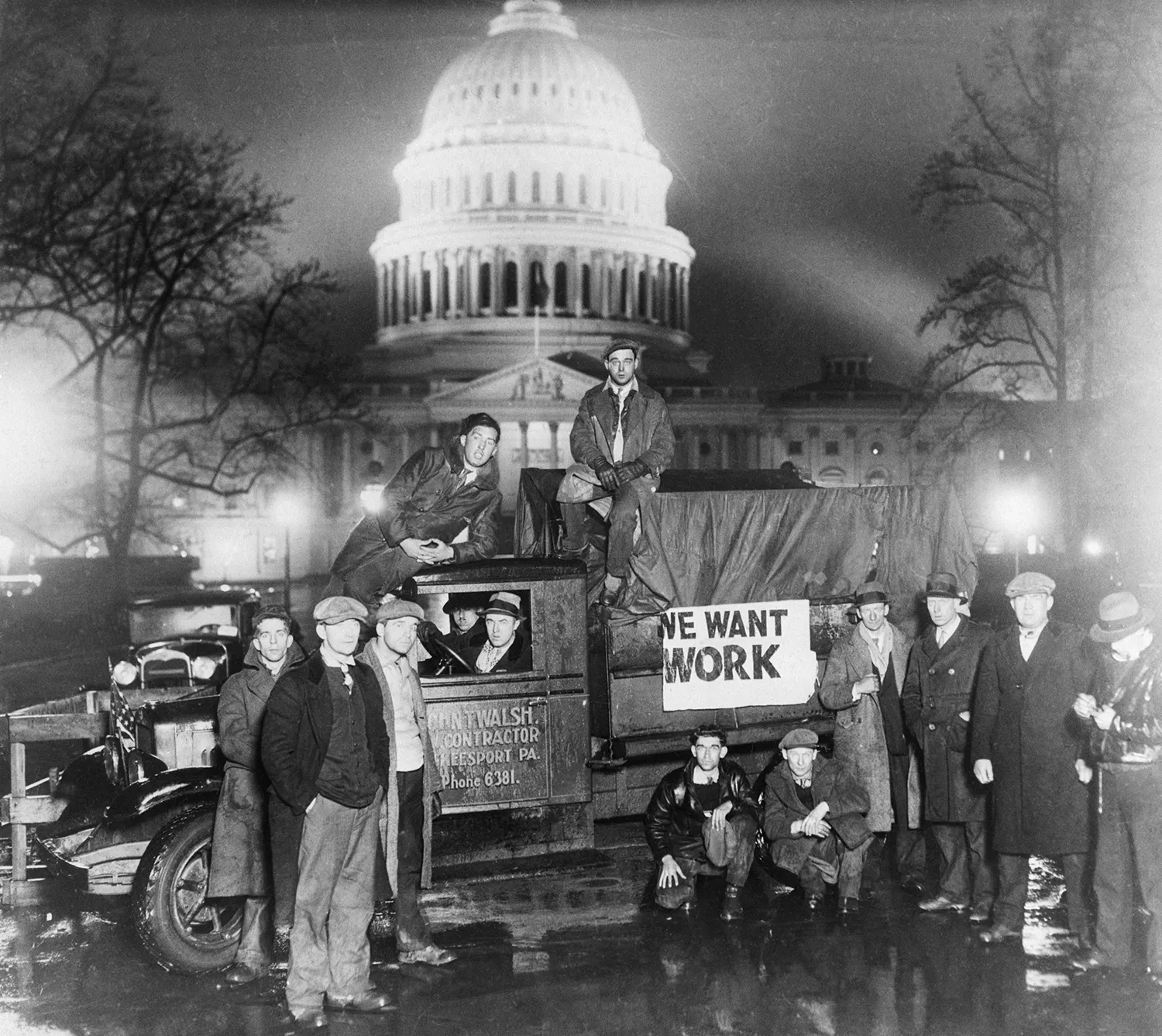

Finally, the drastic Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act contributed largely to the Great Depression of the 1930s, though some economic historians have emphasized the U.S. money supply, the boom-bust cycle in U.S. securities, and unresolved war debts in Europe as the more immediate causes. As a historian who focuses on the 19th century, I will not weigh in, except to say that rapid changes in tariffs change the way the world works. They radically alter international trade in ways that take many years to respond to—and usually result in a vast cascade of unforeseen consequences.

What are the lessons of the past two centuries that could help us understand what happens next? In our current environment, Trump’s tariffs will force many, many companies to back out of settled transactions—just like the farmers, country stores, merchants, and slaveholders of the 19th century. The Pittsburgh-based aircraft supplier Howmet, for example, has already declared a force majeure event, threatening to stop shipments due to tariff impacts. Many other companies across various sectors—particularly those trading with China—are likely to abandon contracts now that the tariffs have taken effect.

Many of the transactions they are backing out of are funded by credit, which in turn is mostly held by banks, hedge funds, insurance companies, and other financial intermediaries. Some of this credit is securitized and sold on to countless other investors. While stock markets are extremely flexible at absorbing losses, the much larger and substantially more complex credit markets are not, as anyone who remembers the 2008 crisis will recall. In 2008, the Federal Reserve bought impaired bonds to reinject liquidity into a frozen market.

Though I am just a historian, I believe that the Fed can handle the chaos we’ve seen so far. But we have yet to contend with the full effects of the China-U.S. trade freeze, and it also remains unclear what follows the 90-day reprieve on the rest of the world. If Congress cannot reassert its constitutional jurisdiction over tariffs—and if power over U.S. trade is now concentrated in the hands of one person, like it was with Jackson in the 1830s—then no central bank will be capable of sustaining the collapse of liquidity that will come with the international depression that I worry is on the horizon.

The post The Awful History of Tariffs and Depressions appeared first on Foreign Policy.