It’s a straightforward part of the Easter story: The Roman governor Pontius Pilate had Jesus of Nazareth killed by his soldiers. He imposed a sentence that Roman judges often inflicted on social subversives – crucifixion.

The New Testament Gospels say so. The Nicene Creed, one of Christianity’s key statements of faith, says Jesus “was crucified under Pontius Pilate.” The testimony of Paul, the first person whose preaching in the name of Jesus Christ is preserved in the New Testament, refers to the crucifixion.

But over the past 2,000 years, it was common for some Christians to deem Pilate almost blameless for Jesus’ death and treat Jews as responsible – a belief that has shaped the global history of antisemitism.

Throughout medieval times, Easter was often a dangerous time for Jewish communities, whom Christians targeted as “Christ-killers”. This perception was integral to the hate that motivated mass violence in Europe as late as the 19th and 20th centuries, including pogroms in Russia and even Nazi genocide.

Why did Christian teachings practically let Pilate off the hook? Why did many Christians allege Jews were to blame?

The Gospels’ story

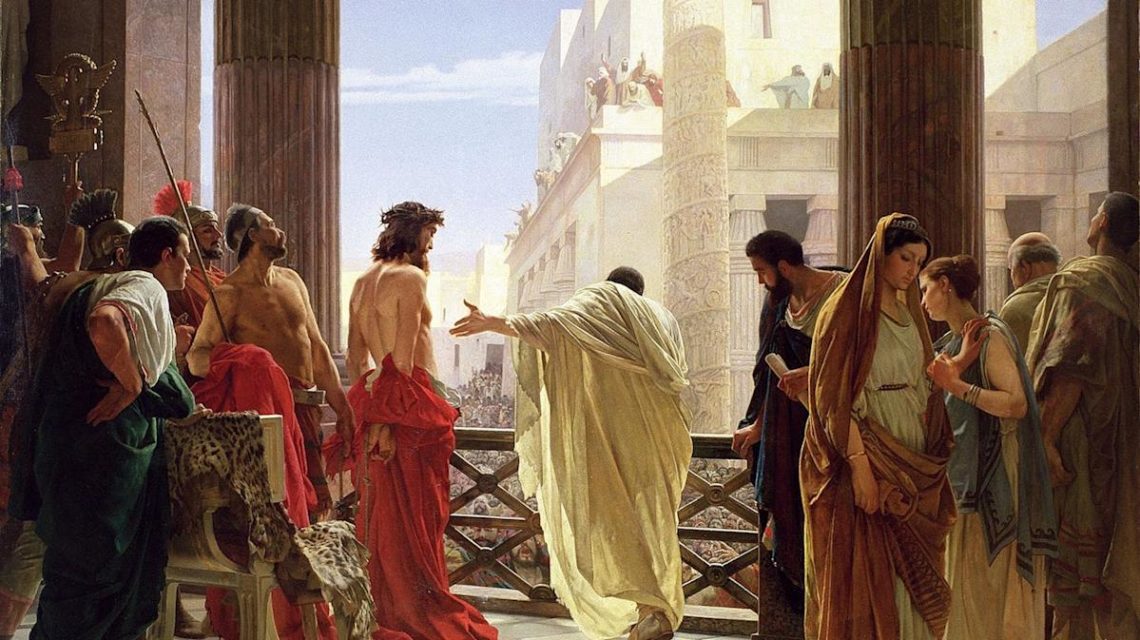

In the Gospels, the first four books of the New Testament, Pilate believes Jesus innocent of any crime. In some of them, he even proclaims so in public.

But the chief priests of the ancient Jewish temple at Jerusalem see Jesus as a charismatic and popular Jewish preacher who challenges their authority. They have Jesus arrested and tried before Pilate during the week of Passover.

Pilate schemes for Jesus’ release, but a riotous crowd clamors for his death. Pilate caves and decides to crucify Jesus, whom Christians believe rose from the dead three days later.

Any reader of the Gospels knows the sequence, though it varies somewhat in each of them. The earliest Gospels, composed at least a generation after Jesus’ death, blamed the chief priests and attending crowd for persuading Pilate to have Jesus crucified. The Gospel of John, written some decades after the other three, portrayed Jews in general as responsible, and so did much of early Christian literature.

One account, written in the mid-second century or later, and not included in the New Testament, even claimed that Jesus’ crucifixion was not ordered by Pilate. Instead, it blamed Herod Antipas, the Jewish ruler of Galilee – the region where Jesus grew up. Other texts from after the first few centuries A.D. said that Pilate became a Christian.

Roman history

Scholars have long debated the historical facts of Jesus’ trial. In my 2025 book, “Killing the Messiah,” I do too.

The Gospel testimonies capture the basics of criminal trials before Roman judges, which were held in public. Judges posed questions to prosecutors and defendants, and had ample power to decide whether a person was innocent or guilty and impose a punishment.

Writers who lived in the Roman Empire portrayed judges as capricious, unaccountable or swayed by menacing crowds. The Gospels reflect this attitude by making Pilate appear bullied into condemning an innocent man.

But from a historian’s viewpoint, there is a crucial problem with the Gospels’ description. Roman judges could and sometimes did face removal from office, property confiscation, exile or even death for executing clearly innocent people. In other words, it seems unlikely that Pilate would have proclaimed Jesus guiltless, but then conceded to pressure and condemned him anyway.

Other ancient writers describe Pilate as someone who was not above offending the Jews of Judaea. According to the first-century Jewish philosopher Philo and the historian Josephus, Pilate had his soldiers carry objects that honored Roman emperors into Jerusalem, which Jewish residents saw as sacrilegious. When crowds protested, he sometimes backed down. But his soldiers attacked an agitated crowd that opposed Pilate’s use of Temple money to build an aqueduct. They also massacred an insurrection of Samaritans – people who also claimed descent from Israelites.

Pilate did not cave to hostile crowds indiscriminately, or do whatever the chief priests wanted. Since Roman prefects like him had to coordinate with Jewish priests to govern Jerusalem, he likely viewed people who incited social disturbance against them as subversive. Jesus would have fit in that category, but neither Philo nor Josephus provides examples of Pilate killing people after acquitting them.

Growing divide

Why, then, did Pilate have Jesus crucified? As many scholars have argued, the simple answer would be that he believed Jesus committed some sort of sedition – not that the crowd simply pressured Pilate into doing so.

Yet, when the Gospels were composed a generation after the crucifixion, they portrayed Pilate as convinced of Jesus’ innocence. As more time passed, other works of ancient Christian literature shifted accountability from Pilate to Jews.

The experiences of Jesus’ early followers help explain this shift. They, like Jesus himself, were Jewish, and they considered him a heaven-sent Messiah. But over the course of the first and second centuries, they increasingly separated themselves from other Jews, until they began to see themselves as members of a non-Jewish movement: Christianity.

In Roman authorities’ eyes, the Christians were troublesome, and they sometimes faced prosecution and capital punishment. In addition, Rome had inflicted atrocities and punitive measures upon Jews after insurgencies – further motivating Jesus’ followers to distance themselves. Their literature became increasingly hostile toward Jews.

Historians and biblical scholars continue to debate why Pilate condemned Jesus. Was it for suggesting that he was the Messiah, or, in Pilate’s wording, “King of the Jews”? Did Jesus incite a crowd disturbance at the Temple during Passover – or were officials worried he could, even inadvertently? Were Jesus and his followers engaged in armed insurrection?

But regardless of the answer, as I argue in my book, responsibility for the crucifixion lies with Pilate – not the chief priests and the Jewish crowd at Jerusalem.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Nathanael Andrade, Binghamton University, State University of New York

Read more:

Nathanael Andrade has received fellowship funding from the Andrew Mellon Foundation/the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, the Institute for Research in the Humanities at the University of Wisconsin, and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation.

The post A Roman governor ordered Jesus’ crucifixion – so why did many Christians blame Jews for centuries? appeared first on The Conversation.