One evening earlier this year, I came downstairs after putting our 4-year-old daughter to bed to find my husband looking at a series of maps of the United States, each showing possible futures given different climate-change projections. In one, my home states of Oklahoma and Nebraska succumb to intense heat; growing crops gets harder. In another, wildfires seem to consume the West. In the Northeast, sea levels rise. Everywhere, average temperatures skyrocket. In Vermont, where I now live, the maps imply that we will still have precious rainfall—and that catastrophic floods will continue.

“Want to watch Netflix?” I said.

It’s not that I don’t care about these predictions of doom. But I admit that my initial response—as the United States has (again) moved to exit the Paris climate agreement, as the protections of the Endangered Species Act are threatened, as the way is cleared for drilling in the Arctic—is to succumb to the temptation of apathy. It’s all too much, I think. I find myself bewildered over how best to respond to these crises—and how to reconcile our daughter, peacefully asleep upstairs, with a burning world that is widely expected to keep burning.

My day-to-day parenting to-do list often goes something like: clean up endlessly after an enthusiastic tornado of a child; work toward a condition that, sometimes, resembles financial security; raise my child to be a decent adult; brace myself for the overwhelm that comes with the pressure I feel to help save a planet in the grips of the sixth extinction.

In my climate-related dread, I know I’m not alone—even though the surgeon general’s report last year about the extreme anxiety coloring the experience of growing numbers of U.S. parents doesn’t mention climate change in the list of concerns causing rampant stress, guilt, and shame among caregivers. Nearly two-thirds of Americans are worried about climate change and feel a personal responsibility to do something about it. Yet when I speak with my climate-conscious friends, family, and fellow mothers, everyone seems to be straining to find agency and purpose.

Raising young children tethers people firmly to the now—to a sometimes joyful, sometimes harrowing, often mundane and narrow world. (As Bluey’s dad laments while carrying a laundry basket in one episode of the eponymous TV show: “This never ends!”) But global climate change tugs many parents’ attention and energy outward—to frightening events and uncertain futures, both of which can feel paralyzing.

I can read scientific papers and the latest United Nations climate reports; I can watch Los Angeles burn. But how do I understand what I’m supposed to do, with my hands?

Lately, to answer that question, I’ve been turning to tiny worlds for help.

I received a microscope for Christmas, and I’ve been disappearing into the preset slides it came with: onion skin (staggered oblong blocks with a dark dot, a nucleus, held in each); a smear of human blood (thousands of scattered discs); a splice of rabbit spinal cord (a spongy oval, misshapen beads around its perimeter). Here, among these orderly universes mere millimeters wide, I find I can breathe.

My husband gave me the microscope, aware of my growing obsession with the small—an interest sparked by my introduction to foraminifera (forams for short), single-celled organisms of an ancient order of protist, which number in the thousands of species. These organisms have inhabited marine ecosystems for more than 540 million years, surviving numerous mass-extinction events.

I first learned about forams when I was researching sea-level rise in Maine’s salt marshes. Forams inhabit almost all marine environments, from deepest water to shore. Perhaps the first record of them in the human canon dates to the fifth century B.C.E., in Herodotus’s Histories, when he makes note of shell-like fossils embedded in the limestone blocks of the Egyptian pyramids.

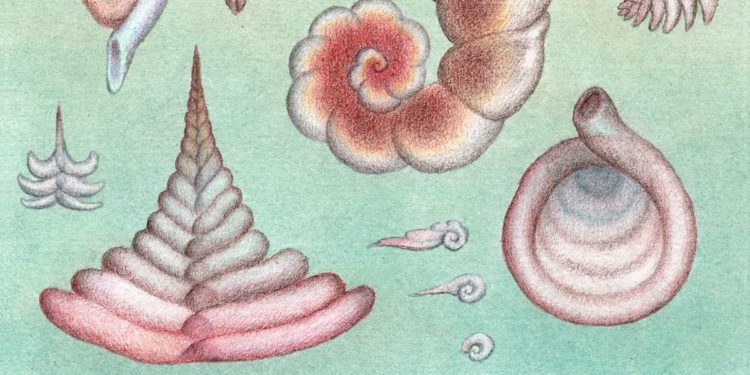

As their longevity indicates, forams are incredibly adaptable and resilient. They build their shells, called “tests,” around themselves, some by collecting minerals from the surrounding waters and cementing them together. The shelters, most of them between half a millimeter and one millimeter long, are single- or multichambered, and shaped like a tube or a sphere, a spiral or a whorl. If you search for an image of a foram, you might see one that looks like a rudimentary shell with a series of ethereal lines shining around it like the sun’s corona. These are pseudopodia, or rhizopodia (rhizo meaning “root”), and are made up of cytoplasm; forams extend and retract these cytoplasmic threads as needed for moving, feeding, and constructing their shells.

Do I digress?

For me, forams were not a digression, but a revelation. Because, listen: Many species of foram are highly site-specific; they evolved within a narrow set of conditions, such as the temperature and oxygen content of the water and the mineral makeup of the surrounding sediments. These site conditions are not preferences but nonnegotiable bounds of survival. The more closely I looked at forams, the more I realized that they might have lessons to impart to humans about our physical place in a changing world.

The forams’ shells keep the fossil record. When the cell dies, the shell remains. The shape and structural content of these shells, as determined by their immediate surroundings, gives precise information about the environments that they exist in today, or that existed millennia ago. Their fossils are snapshots: miniature witnessings of a particular place and moment of transformation. It is thanks to this place-bound existence that forams have contributed to our understanding of massive, global change over eons.

Foram-fossil-informed discoveries include: changes in sea levels during the Carboniferous period (more than 300 million years ago), fluctuations in the oxygen content of the oceans during the Jurassic (roughly 201 million to 145 million years ago), and glacial activity during the Quaternary (beginning about 2.5 million years ago). The fossils tell us about present-day conditions as well. On a slide under a microscope, scientists can read the work of those tiny cytoplasmic arms. Perhaps a shell has been partly dissolved by acid in an industrial waterway, or is deformed by an encounter with pollutants. As Pratul Kumar Saraswati, an earth sciences professor at the Indian Institute of Technology in Mumbai, wrote: “Foraminifera is both the clock and the recorder of the Earth’s history. It has played a crucial role in developing our understanding of the evolution of life and the environment on Earth.”

Pulling myself back to the human-scale world, I lift my eyes and look out the window with a new clarity. I think of the river down the street that flooded about a decade ago; the summers of record-breaking heat; the shifting composition of birdsong in the trees; the human community, in all its messy complexity. From this site-specific view, I don’t long for escape. Foraminifera have helped me remember that I, too, am tiny and fleeting. The conditions of my physical existence are narrow. This river valley defines my visible horizon. I breathe oxygen made from these trees. And with that remembrance, I feel a wave of relief. This is a world I can touch—a scope I can manage.

The benefits of local, place-based conservation and environmental work are well documented. The restorative power of maintaining a close relationship to nature is demonstrated as well: Forest bathing, for one—from the Japanese practice of shinrin-yoku, in which mindful, sensory immersion in forests is a therapeutic exercise—has been shown to reduce stress and alleviate symptoms of depression.

But I suppose what I’ve been seeking goes beyond even this. Like the foraminifera building their shells, I want to construct something for myself and my family. As the scientist and author Robin Wall Kimmerer, an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, writes in Braiding Sweetgrass:

Being naturalized to place means to live as if this is the land that feeds you, as if these are the streams from which you drink, that build your body and fill your spirit. To become naturalized is to know that your ancestors lie in this ground. Here you will give your gifts and meet your responsibilities. To become naturalized is to live as if your children’s future matters, to take care of the land as if our lives and the lives of all our relatives depend on it. Because they do.

The very small reminds me that I exist within limits, within constraints, within particular environments and communities and moments in time. From this narrow space, I can find expanded agency with which to act, and with which to parent.

So this past winter, I paid attention to the northern cardinal that sang at dawn. I began reading my daughter her first chapter books. I also began the process of getting my prescribed-fire certification, hoping to help with local ecosystem restoration. This spring, my daughter and I will pull invasive knotweed from our yard, and we’ll plant the wildflower seeds we collected late last summer. When the weather turns warmer, I’ll take her to swim in the river. Through these acts, I can construct the foundation of a worldview. I can extend my arms to what I can touch and taste. I can practice building a structure, a house—a home—where caring for my daughter and caring for the planet are not two separate things.

The post Parenting Lessons From One of Earth’s Tiniest Creatures appeared first on The Atlantic.