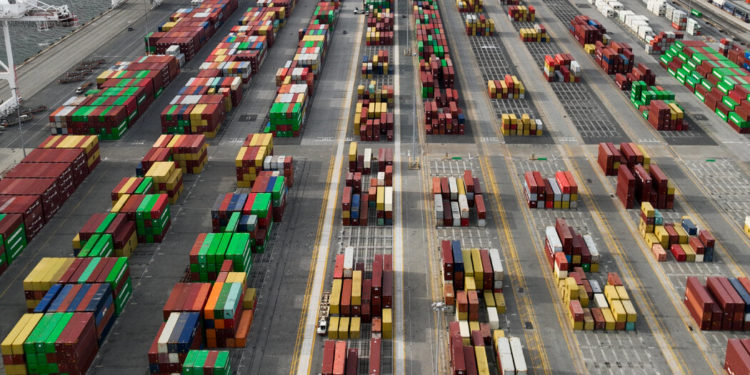

President Trump unveiled his most expansive tariffs to date in a ceremony at the White House on Wednesday, saying he will impose a 10 percent tariff on all trading partners except Canada and Mexico, as well as double-digits tariffs on dozens of other countries that administration officials said had treated the United States unfairly.

The move was a significant escalation of Mr. Trump’s trade fight and is likely to ripple through the global economy, driving up prices for American consumers and manufacturers while inciting retaliation from other nations. While Mr. Trump had been saying for weeks that he would impose “reciprocal tariffs,” his announcement went far beyond what many economists and analysts had expected.

The president said he would sign an executive order applying a universal base-line tariff of 10 percent to countries around the world, plus levies ranging from 1 percent to 40 percent on dozens of trading partners.

They include the European Union, China, Britain and India, all of which would also face higher reciprocal tariffs based on trading practices that Mr. Trump has deemed unfair. The 10 percent base-line tariffs will go into effect on Saturday and the reciprocal rates next Wednesday, White House officials said.

The moves will shatter the global trading system that the United States had helped build up since the Second World War, as the higher tariffs of Mr. Trump’s own devising replace the rates that the United States negotiated at the World Trade Organization. White House officials said pernicious trading practices by other countries had led to large and persistent trade deficits for the United States and had created a national emergency.

Under Mr. Trump’s plan, the United States will add a new 34 percent tariff on Chinese goods on top of the 20 percent tariff that he had imposed on Beijing in recent months.

Some of Mr. Trump’s steepest rates apply to U.S. allies, including 20 percent on imports from the European Union and 24 percent on goods from Japan.

Eswar Prasad, a professor of trade policy at Cornell University, said, “The era of increasingly free and extensive international trade, built upon a rules-based system that the U.S. was instrumental in shaping, has drawn to an abrupt end.”

He added, “Rather than fixing the rules that many U.S. trading partners admittedly took advantage of to their own benefit, Trump has chosen to blow up the system governing international trade.”

The value of tariffs for all the goods imported by the United States last year was $78 billion. With the new tariffs announced on Wednesday, the figure would skyrocket to more than $1 trillion, according to an analysis by Trade Partnership Worldwide, a research firm based in Washington.

Canada and Mexico will not be hit by the new measures, though they will remain subject to the 25 percent tariff that Mr. Trump imposed on many of their products last month in addition to separate U.S. tariffs on global steel, aluminum and cars. The car tariffs go into effect on Thursday.

The new tariffs will also not apply to products that Mr. Trump has already hit with separate levies, including steel, aluminum, and vehicles and their parts. Energy and “other certain minerals that are not available in the United States” will also be excluded.

Wall Street shuddered as Mr. Trump announced the tariffs, with early market reaction pointing to a further slide in the stock market and a weakening dollar. Futures on the S&P 500, which allow investors to trade the index outside normal trading hours, slumped nearly 2 percent, erasing a gain of 0.7 percent while exchanges were open. Global stock benchmarks also came under pressure. Futures on the Japanese Nikkei 225 index fell 2 percent before Asian markets opened.

Justin Begley, an economist at Moody’s Analytics, described the new tariffs as “extraordinarily high and certainly bigger than what we had forecast.” Pointing to volatility in the financial markets, he said, “It feels like there’s a flight to safety right now because of expected weaker growth and higher inflation.”

Trade analysts also expressed alarm. Scott Lincicome and Colin Grabow, trade experts at the Cato Institute, which promotes free markets, argued that the administration’s justifications for the tariffs were flimsy and conflicting.

“With today’s announcement, U.S. tariffs will approach levels not seen since the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, which incited a global trade war and deepened the Great Depression,” they said in a statement.

Mr. Trump defended his measure, saying the global trading system that had been in place for decades was harming the United States and needed to be changed.

“For decades, the United States slashed our trade barriers on other countries while those nations placed massive tariffs on our products and created outrageous, non-monetary barriers, to decimate our industries,” Mr. Trump said. “Those days are over,” he added.

Robert E. Lighthizer, the U.S. trade representative in Mr. Trump’s first term, said the United States had a giant trade imbalance that was “brought about not because of real economics but the industrial policy of foreign countries.”

“The trillion-dollar trade deficit is a huge problem, and the president has to do something about it,” he said. “You need a period of profound change.”

White House officials said that the administration did not intend to haggle with other countries over lowering tariff rates, but that reciprocal tariffs could be reduced if the U.S. trade deficits fell and countries stopped their unfair practices. The White House has also threatened further tariffs on countries that retaliate against the United States.

Mr. Trump described his approach as “kind,” saying he was charging other countries only half of the reciprocal rate that his administration had calculated should be applied, based on their trade practices. He said tariffs were needed to boost domestic production and turn the United States into an “industrial powerhouse.”

“We’re going to start being smart, and we’re going to start being very wealthy again,” Mr. Trump said.

Some business groups expressed unease about the president’s wide-ranging tariffs. Jay Timmons, the president of the National Association of Manufacturers, said his group was still parsing the finer details. But he added that “the high costs of new tariffs threaten investment, jobs, supply chains and, in turn, America’s ability to outcompete other nations and lead as the pre-eminent manufacturing superpower.”

David French, the executive vice president of the National Retail Federation, said in a statement that the tariffs would “equal more anxiety and uncertainty for American businesses and consumers.”

Tariffs are paid for not by foreign countries or suppliers but by U.S. importers, he said, adding that “the immediate implementation of these tariffs is a massive undertaking and requires both advance notice and substantial preparation by the millions of U.S. businesses.”

Mr. Trump has largely dismissed concerns that his tariffs — essentially a tax on imports — could raise prices for American consumers and businesses or prompt retaliation that would hurt farmers and other exporters.

“Every prediction our opponents made about trade for the last 30 years has been proven totally wrong,” the president said at one point during the Rose Garden ceremony, as he looked to pre-emptively rebut complaints that his tariffs could cause economic upheaval.

“We can’t do what we’ve been doing for the last 50 years,” he said.

Even before Mr. Trump’s announcement on Wednesday, the tariffs that he had already imposed on China, Canada, Mexico and certain products had brought the average U.S. tariff rate to 12 percent — the highest level since World War II, analysts at Deutsche Bank Research said.

They added that the announcement of reciprocal tariffs on Wednesday could increase tariffs to levels not seen in the United States since the early 1930s, after the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act was passed.

Governments across the world have been preparing to retaliate, increasing the potential for a destabilizing economic battle that drives up costs as Mr. Trump tries to force supply chains back to the United States.

Some governments have responded to Mr. Trump’s threats by rolling back their own tariffs. Israel said on Tuesday that it would cancel all remaining tariffs on American imports. Effective Monday, Vietnam also cut tariffs on a variety of products, including liquefied natural gas, ethanol, chicken legs, cherries, wood and cars.

The Canadian and Chinese governments have already countered Mr. Trump’s previous tariffs with levies of their own. Governments in Europe, in Mexico and elsewhere were waiting to see Wednesday’s measures before announcing their responses. European Union officials have discussed placing trade barriers on services, using a trade weapon that was developed in 2021. That tool could allow the bloc to impose restrictions or penalties on companies like Google, Meta or even American banks.

Mr. Trump argues that tariffs will encourage companies to move factories into the United States, and he has hailed investment announcements from chipmakers, car manufacturers and others.

But economists say that since tariffs raise prices for imported products and manufacturing inputs, they can slow the economy.

Nancy Lazar, chief global economist at Piper Sandler, now reckons that the U.S. economy may contract 1 percent in the second quarter “because you’re going to be increasing prices more aggressively and it’s going to negatively impact the consumer space more than we had anticipated.”

Ms. Lazar had previously expected a flat quarter. “It’s an immediate hit to the economy,” she said.

Satyam Panday, the chief U.S. and Canada economist for S&P Global Ratings, said, “If manufacturers have to be paying more for their input, we are most likely going to see prices on the output also increase.” He added that was “inflationary pressure building.”

Mr. Trump and his supporters have acknowledged that there could be some pain for the economy and consumers as global supply chains reorganize but have said it will be worth the cost.

After the president wrapped up his remarks Wednesday and went back inside the White House, a few cabinet secretaries and members of Congress lingered in the Rose Garden with men in hard hats and vests who had been invited to attend but seemed stunned to find themselves there.

“It’s just so great,” Danny Hess, a coal miner from Russell County, Va., said as he looked around. Asked if the president’s critics were right that tariffs could throw the country into a recession, Mr. Hess, 62, said with a shrug, “We’ll just have to wait and see.”

He said the uncertainty did not worry him, because “things have been so disastrous for so long” anyway.

Reporting was contributed by Joe Rennison, Colby Smith and Lazaro Gamio from New York and Alan Rappeport and Shawn McCreesh from Washington. Tung Ngo contributed research.

Ana Swanson covers trade and international economics for The Times and is based in Washington. She has been a journalist for more than a decade. More about Ana Swanson

Tony Romm is a reporter covering economic policy and the Trump administration for The Times, based in Washington. More about Tony Romm

The post Trump Unveils Expansive Global Tariffs appeared first on New York Times.