The comedian Andrew Schulz made his first-ever appearance on The Kardashians in the 26th season of the family’s reality TV reign. Kim had recently seen him at Netflix’s Tom Brady roast in May, and she was recounting her displeasure at being mocked onstage and booed by the crowd.

“And then this guy afterwards did an interview,” Kardashian said, as a clip from Schulz’s podcast flashed across the screen, “and was like, ‘Kim was so robotic.’”

Another comedian had taken aim at Kardashian’s sex life. “Like, am I supposed to sit there,” she continued, “and be like, ‘How innovative, you called me a whore?’”

Kardashian didn’t know Schulz’s name, or at least suggested as much. And yet, as with a growing swath of contemporary culture and politics, she had been caught up in his and his peers’ insult comedy. All of which is to say that one of America’s most bankable and savvy celebrities had become something like an average media consumer.

“Everyone gets these jokes,” goes Schulz’s long-running tagline—a familiar claim to providing equal-opportunity offense. In the months since the Brady roast, it has approached a statement of fact. For his recent Netflix stand-up special, LIFE, which focuses on his and his wife’s struggles with in vitro fertilization, Schulz filmed a promo with Matt Damon. (Schulz now has a one-year-old daughter.) He was the ostensible target of a Kendrick Lamar lyric in November after remarking that white men with Black girlfriends grow their beards for “more cushion when they get slapped the fuck out of.” In October, with 29 days left to go in the presidential campaign, he interviewed Donald Trump on his podcast, cackling as the president described himself as “basically a truthful person.”

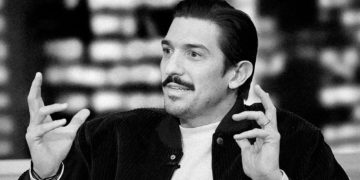

“I mean, he just said something that made me die laughing,” Schulz recalled as he sipped a Guinness at a Tribeca steakhouse one afternoon in March. His reaction, he said, wasn’t meant as a denigration; he appreciated Trump’s hedging. “And it’s also the most truthful statement you can say. Nobody looked at it like that. Anybody who goes, ‘I’m a truthful person,’ you are a liar.”

Since the president’s reelection, the go-to shorthand for the class of comedians and podcasters in which Schulz operates is “manosphere”: These are the men in an ascendant media space, often associated with Joe Rogan, who are said to have smoothed Trump’s return to power by having him at their on-camera hangouts. Schulz described Rogan to me as “the greatest influencer in the history of the world” and he outlined his theory that “comedians are often successful when what they do well meets a societal necessity.” Still, he professed not to be preoccupied with his place in the moment—even, or especially, as legacy outlets have so clearly been.

“We’d rather talk about some joke that we’re bombing with or talk some shit about some person,” Schulz said. “After the Trump thing, I wasn’t like, ‘We got it now.’ After the Trump thing, I was like, ‘We just interviewed the president of the United States, what the fuck?’”

There is no doubt a masculine current running through this vision of politics as pop culture, and the manosphere has come to stand for a recognizable set of personalities. But Schulz has ultimately thrived in a far broader sense. As he promoted his special in recent weeks, he presented as an everyman public intellectual, discussing Social Security and the American dream with the Elon Musk–affiliated venture capitalist hosts of the All-In podcast. He dissected dating mores with Megyn Kelly, Democratic strategy with Bari Weiss, and the notion of good-faith conversations with Dax Shepard. One of his recurring riffs, as displayed in an exchange with fellow comedian-podcaster Theo Von, deals with his respectful fear of Candace Owens.

The modern media diet is increasingly structured around short video clips. In a raucous and loosely interconnected sphere, smack talk is the coin of the jittery realm. To enter the Schulz fray, as Trump did, is to be one of the guys, but it is also simply to play ball: to show up with whomever, whenever, to talk about whatever. This, as it stands, constitutes a kind of political strategy. The first guest on California governor Gavin Newsom’s new podcast was the conservative activist Charlie Kirk. Newsom told the youth-whispering provocateur that his 13-year-old son had wanted to take the school day off to meet him. The following day, Kirk told Sean Hannity that he saw the outreach as an emblem of Newsom’s ambition and charisma.

“White people didn’t really find out about me until Rogan,” Schulz, 41, told me.

He grew up as a student of Black comedians—Patrice O’Neal, Bernie Mac, Eddie Murphy, Def Comedy Jam—and listening to hip-hop radio. As a Manhattan public school kid in the ’90s, he said, moving between the Upper East Side and the East Village, Seinfeld wasn’t discussed. His parents were dance instructors who ran a studio, and his father, an Army veteran, took a particular interest in preserving swing traditions from Harlem.

As a child, Schulz liked attention, but he didn’t try out stand-up until college in Santa Barbara, when he was managing a restaurant that happened to hold a comedy night. In the mid-2010s, he and the radio stalwart Charlamagne tha God met as hosts of the MTV2 show Guy Code. They launched a still-running podcast, The Brilliant Idiots, and in 2020, Schulz released his first special for Netflix during the coronavirus pandemic. It attracted some measure of backlash for his jokes referring to a “Wuhanic plague,” but nothing that truly stuck to him. “I was basically speaking to what people were feeling,” Schulz said, “but wasn’t represented on the news because it was so polarized.”

It was, in retrospect, a gold rush period for a certain strain of podcast. Schulz made his first of nine appearances on The Joe Rogan Experience in 2019. “Joe gets excited. He’ll just message me clips of me saying something,” he said. “He’d be like, ‘Brother, this is so fucking hilarious.’” Robert F. Kennedy Jr. was starting to gain some traction—he was a fringe figure and a game guest for Rogan and Von. Flagrant, Schulz’s flagship podcast, was evolving from a sports show to a catchall discussion of news and pop culture.

By now, the lengthy and free-ranging format has formed a low-hanging trope, and the source material for multiple Saturday Night Live sketches. “I don’t know how they do it,” Schulz said of his show’s listeners consuming its hours-long episodes. He and his team have learned to time their installments with the rhythm of the work week. “If you’re working at a desk, if you’re just pushing paper, man,” he said, “you need distraction.”

Relative to some of its counterparts, Flagrant offers little in the way of self-help or vulnerability. To the extent that it has attracted the kind of parasocial audience commonly associated with successful podcasts, the relationship can skew antagonistic. During interviews, Schulz coils his wiry frame under itself, ready to explode with laughter at the very edge of his seat. On Reddit, some of his most avid followers beg him to stop interrupting.

“He’s just as entertaining on Club Shay Shay and Breakfast Club as he is on Rogan and Theo Von,” Charlamagne recently told me, referring to former NFL tight end Shannon Sharpe’s rising interview series and his own long-running hip-hop show. “If you got an opinion about him and you’re expressing it online, the algorithm don’t know the difference.”

After we hung up, Charlamagne texted me a link to a study that he came across after he interviewed Kamala Harris during the presidential campaign. At the end of 2023, The Breakfast Club was the number two podcast among Black weekly listeners; number one was Rogan.

In 2022, Schulz signed for representation with CAA. He sold out two nights at Madison Square Garden last year. He has not become a red-carpet staple, but he has begun moving in such circles. A Page Six item from July placed him at a Bridgehampton party at which Leonardo DiCaprio helped out an overserved guest. Scooter Braun, Justin Bieber’s and Ariana Grande’s former manager, came across Schulz’s work in the late 2010s and reached out. He is a consulting producer on the comedian’s recent special.

“Whether it be finding musicians to models to actors to comedians or even a script,” Braun told me, “I’ve always felt like, if I like it, there’s nothing extraordinary about my taste, so probably everyone else will like it too.”

Schulz compared contemporary podcasting to magazines in the sense that cultural niches could emerge from a particular show. “Barstool had the kind of fraternity brother culture,” he said, “and I was like, ‘What’s our version of it in the city?’” Online, some of his backers include a class of aughts-era New York rappers (50 Cent, Fabolous) and the breakout country singer Jelly Roll.

The crossover has a somewhat au courant shape. Von recently attended an Oscars week poker night hosted by Timothée Chalamet at the Chateau Marmont; the actor had appeared on his show a few months prior. Several weeks later, the comedian was at a fight where UFC CEO Dana White, a longtime friend of Trump’s and a prominent connector in the network of podcasts that hosted the president, gave a warm welcome to Andrew and Tristan Tate upon the brothers’ return to the United States.

In March, I attended a recording of Flagrant at its Nolita studio. The space, inspired by the architecture of a nearby subway station, is set up in the manner of a talk show. The three hosts ran through the topics of the day, including Stephen A. Smith versus LeBron James and Andrew Cuomo’s attempt at returning to politics. “You think he’s got it?” Schulz asked. AlexxMedia is an on-camera personality, videographer, and producer from Far Rockaway, a predominantly Black and Latino neighborhood at the eastern edge of Queens. During breaks in the three-hour taping, he and Schulz’s manager, a son of Moroccan Jews from Beverly Hills who was hoping to book Eric Adams, sparred over the Israel-Hamas war. (Moments after I met AlexxMedia in the studio, he had asked me if I was Jewish.)

The banter assumes a level of intimacy with the lives of both its comedians and off-camera staff. The group reviewed footage of Schulz’s appearance at a WWE event the night prior, and he reflected on how, following his IVF-themed special, he had become “the face of sperm that sucks.” They grilled a producer and business-side employee for an extended segment on how the two men ended up sharing a New Year’s Eve kiss. After the recording, I caught up with Mark Gagnon, one of the hosts and a French American comedian from Orlando whose curly, shoulder-length-plus hair draped over a hockey jersey. To him, the community around Rogan had the feel of a New York art collective.

“At the lowest level, humor that has to do with race, religion, or culture is just awful,” Schulz told me the following week. “At the highest level, those are the best jokes ever written.” He had come to think of his show’s ethos in terms he applied to the children of immigrants—curious and “not embarrassed about making an effort to improve our lives.” (Schulz’s mother was born in Scotland.)

Growing up in New York, he said, “We would always ask, ‘What are you?’ And it’s not on some fucking NPR dude trying to cozy up with the Uber driver.”

The night before we met up, the Trump administration had released a batch of JFK assassination files, keeping a promise that the president had made to Rogan on his show. The subject has long been one of Rogan’s pet obsessions, and in general a core fascination of the conspiratorially minded. In the morning, with the records having produced much fanfare and little revelation, Jack Schlossberg, the grandson of JFK, posted photos of Schulz, Rogan, and his cousin RFK Jr. “These guys deserve to be called out too for spreading disinformation,” he wrote.

The criticism is nearly as entrenched as the ecosystem it is fighting. Over an eight-day stretch this month, Rogan hosted one guest who has suggested that Israel was behind 9/11, and another who has said it was not Hitler but Churchill who bore primary responsibility for World War II. During the same period, Owens appeared on This Past Weekend w/ Theo Von and claimed that Israel is blackmailing the US, with Jeffrey Epstein having acted as an agent of the country.

In October, a few days after Trump appeared on The Joe Rogan Experience, Marc Maron, the comedian and podcaster who has also hosted a president on his show, published a short essay on “The Democratic Idea.”

“The anti-woke flank of the new fascism is being driven almost exclusively by comics, my peers,” Maron wrote. “Whether or not they are self-serving or true believers in the new fascism is unimportant. They are of the movement.”

As I read an excerpt to Schulz, he rolled his eyes. “I think that’s the most used word that nobody really knows what it means,” he said.

“I would just say I’m surprised at how pedestrian the thought is for Marc,” he went on.

It was a fairly measured response, but later, over text, he found some more acid. Schulz said it was important to talk to people with whom you disagree, and that Maron, “who at one point was considered a unique and thoughtful comedian, now has the opinions of a girl that dyes her armpit hair.”

As 28-year-old campaign adviser Alex Bruesewitz organized Trump’s podcast tour, he thought back to an earlier era of the president’s fame. On shows like Schulz’s, Bruesewitz, the author of Winning the Social Media War, wanted to showcase Trump as a man who had once lit a cigarette for Kate Moss, inspired scores of rap lyrics, and had his name on the building where Michael Jackson lived for a time.

After an initial meeting with Schulz, “I knew instantly that those two would have great chemistry,” Bruesewitz recently remembered. “Both brash New Yorkers.”

He considered Schulz’s audience to be center-left, noting the comedian’s close relationship with Charlamagne, who has become a fixture of Democratic media outreach. That, he reasoned, was the point. “If you watch the president’s episode on Flagrant and you read the comments,” Bruesewitz said, “You have thousands and thousands of people saying, ‘Wow, this is the first time I’ve heard Trump this way before, and I like this guy.’”

As I sat with Schulz, a passerby from northern New Jersey interrupted to ask for a photo. “You’re the truth, brother,” he said. He and his wife were navigating IVF, and she cried as they watched the special. “I was laughing,” he said. “God bless you, man.”

A waiter stopped by to say that he and his wife had also watched two nights ago. He had seen Schulz perform stand-up years ago. “I remember a joke,” he said. “Dominican plumber.”

Schulz, as he often says, doesn’t care for politics. He never thought to endorse a candidate, and he said that Flagrant tries to provide a caveat that the show is only “our funny version of what is going on.”

Nonetheless, as he and his fellow comics have amassed their followings, he couldn’t help acknowledging the sway he had acquired. They were competing less with each other than with traditional media. “Everybody thinks they’re normal,” he said. “So if you think you’re normal and you see us dominating culture, you have to find a way to make me abnormal, which is ‘manosphere,’ ‘sexist,’ whatever. Welcome to America.” To treat his circle as “some obscure small thing,” he figured, “will be one of the great failures of a party.”

“How far does the pendulum need to swing?” Schulz recently asked his Flagrant cohosts. He wondered if there might ever be a future when “there’s this thirst for, ‘Alright, just tell me the boring truth.’”

When he appeared on Von’s show the following week, the pair agreed that they hadn’t influenced the election. “I think for like a week,” Von said, “I started smoking my own nuts and thinking I was like fucking J. Edgar Hoover or somebody.” But the subject remained at the fore of their exchange. “There’s so much bullshit information,” Schulz said, “and we’re guilty of that too. We just spout whatever on the fucking mic, and who knows if it’s true or not.”

A version of the push and pull also came up when I spoke to Schulz. He observed that we could be at the end of a bubble, and that comedy might function better in a rebellious mode. “I just think that we are what people are listening to now,” he said, “but that could change tomorrow.”

More Great Stories From Vanity Fair

-

Gwyneth Paltrow on Fame, Raw Milk, and Why Sex Doesn’t Always Sell

-

Carrie Coon on Her “Humiliating” White Lotus Hookup

-

Yale’s Fascism Expert Is Fleeing America

-

How Snow White’s Failure Has Turned Rachel Zegler Into a Scapegoat—and an Icon

-

Meghan Markle and the Future of Tradwife Mompreneurs

-

Candace Owens vs. Jessica Reed Kraus: The Massive MAGA-World Spat

-

The Alexander Brothers Built an Empire. Their Accusers Say the Foundation Was Sexual Violence.

-

Silicon Valley’s Newfound God Complex

-

A Juror From Karen Read’s First Murder Trial Has Joined Her Defense Team

-

Meet Elon Musk’s 14 Children and Their Mothers (Whom We Know of)

-

From the Archive: The Temptation of Tiger Woods

The post Andrew Schulz and the New Media Nerve Center appeared first on Vanity Fair.