Welcome to Foreign Policy’s South Asia Brief.

The highlights this week: Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi suggests a thaw with China during a podcast appearance, U.S. Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard visits New Delhi, and Pakistan grapples with a spate of terrorist attacks.

Sign up to receive South Asia Brief in your inbox every Wednesday.

Sign up to receive South Asia Brief in your inbox every Wednesday.

Sign Up

By submitting your email, you agree to the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use and to receive email correspondence from us. You may opt out at any time.

Enter your email

Sign Up

Modi Comments on China Raise Eyebrows

A recent podcast interview with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has garnered extensive attention in India. His three-hour appearance on the Lex Fridman Podcast was a strikingly long engagement for a notoriously media-shy leader. Modi discussed foreign policy extensively, but what stood out most were his comments about China.

Modi spoke positively about New Delhi’s relations with its main strategic competitor, which have been especially tense since a 2020 border clash in Ladakh—the deadliest since the 1962 war between India and China. Modi emphasized the importance of strengthening bilateral ties and said that normalcy has returned to the two countries’ border, even though much of it remains disputed.

During Modi’s decade-plus in power, and especially since the Ladakh clash, India has argued that its relations with China can’t stabilize until the border issue is sufficiently addressed. But Modi seemed to signal that he is ready to usher in a new phase in relations. Beijing, which has long contended that the two sides should pursue more cooperation, responded positively.

A few factors might explain why Modi said what he did, and why now: recent developments in China-India relations, India’s economic situation, and U.S. policies under President Donald Trump.

In recent months, India-China ties have quietly started to thaw. Last October, the two sides reached a deal for their troops to resume border patrols around Ladakh. A flurry of high-level engagements came at the end of the year, including a meeting between Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping on the sidelines of a BRICS summit. In January, India and China agreed to resume direct flights.

This shift isn’t entirely surprising: India-China relations, despite the border dispute, are rarely hostile. The two countries partner in multilateral forms, and they share some common global interests—such as embracing non-Western economic models and countering Islamist terrorism. Even after the Ladakh clash, the two militaries continued to hold regular talks, resulting in last October’s patrolling deal.

India likely wants to leverage the diplomatic space freed up by this mini-detente to advance more economic cooperation. India-China trade has remained robust since the Ladakh clash. But Chinese foreign direct investment has slowed down as it has been subjected to heavier scrutiny. Last year, India’s chief economic advisor called for loosening this scrutiny.

Increased Chinese investment in India could help strengthen key but sputtering sectors, such as manufacturing, as well as growing and high-priority sectors, including renewables. It could also ease India’s trade deficit with China, which is India’s biggest source of imports. A smoother bilateral relationship gives New Delhi the political currency to make a pitch for more investment.

Trump’s views likely contributed to Modi’s comments; the U.S. president has signaled a desire to reduce tensions with China and said that he hopes to partner with Xi on peace and security. If there is any reason to believe that the United States would be less forthcoming in wanting to help India counter China, then New Delhi would prefer to avoid serious tensions, too.

Reducing U.S.-China tensions could be a good thing for India: It would reduce the risk of Beijing retaliating against India, including through border provocations, for its close partnership with Washington. At the same time, Trump’s new tariffs against China and tariff threats against India give New Delhi another incentive to turn to Beijing for more commercial cooperation.

All this said, Modi’s comments shouldn’t be mistaken for an announcement of rapprochement. India and China are still at odds over so much: China’s close alliance with Pakistan, India’s security partnership with the United States, the Dalai Lama’s longtime presence in India, and China’s strong naval presence in the Indian Ocean region (among other matters).

India and China are also Asia’s two largest nations, and they both view themselves as civilizational states. This makes them natural competitors.

Still, Modi’s pitch for more partnership with Beijing is freighted with significance. Better bilateral ties could boost his country’s economy, enable New Delhi to focus more attention on challenges in its immediate neighborhood, and take away a major distraction from India’s great-power aspirations.

What We’re Following

Tulsi Gabbard visits India. Amid growing Indian concerns about Trump’s tariff threats, U.S. Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard’s trip to New Delhi this week was a welcome distraction. Gabbard attended a conference of intelligence leaders in New Delhi, but she also met with Modi and other senior Indian officials and gave a speech at the Raisina Dialogue summit.

Gabbard touched on issues that resonate with Indian officials and much of the public, such as fears about Islamist terrorism. She spoke about the U.S.-India partnership and the special chemistry between Modi and Trump, as well as discussing her own experiences as a Hindu.

However, one delicate issue arose: Indian officials pressed Gabbard to take a tougher stand against Sikh separatists in the United States. Last year, the U.S. Justice Department indicted a former Indian intelligence officer on allegations of orchestrating a failed assassination attempt against a prominent pro-Khalistan leader in New York. Gabbard did not speak publicly about the Khalistan issue while in India.

India has apparently received some positive signs that Trump could see eye to eye with it on the issue. But hopes that the Justice Department will wind down the investigation are likely misplaced: Trump is unlikely to shrug off an alleged violation of U.S. sovereignty and has nominated a supporter of Sikh rights as head of the Justice Department’s civil rights division.

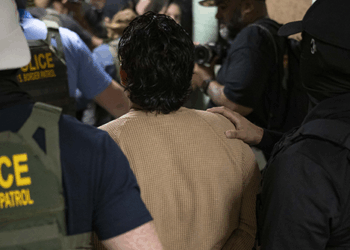

Rising violence in Pakistan. Since ethnic separatists in Pakistan’s Balochistan province seized a passenger train last week, Pakistan has faced dozens of terrorist attacks. They have ranged in intensity, from small-scale sniper firings to suicide bombings. Most have taken place in the provinces of Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, which border Afghanistan.

The Balochistan Liberation Army, which carried out the train hijacking, is responsible for many of the recent attacks, along with as the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan, which recently announced its annual spring offensive.

The violence risks straining Pakistan-India ties, which have been relatively stable since the two countries signed a border agreement in 2021. Pakistani officials have publicly accused India of sponsoring the train hijacking. Indian operatives may be behind the assassination of Lashkar-e-Taiba leader Zia-ur-Rehman on March 15; the group has carried out multiple attacks in India.

All of this will unsettle Pakistan, especially in light of Modi’s recent harsh criticism: On the Lex Fridman Podcast, he said that “wherever terror strikes in the world, the trail somehow leads to Pakistan.” This won’t be received well, yet Pakistan—grappling with economic stress and political turmoil—can’t afford a resurgence of tensions with India.

U.N. secretary-general calls for support for Rohingya. U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres visited Dhaka, Bangladesh, last week, where he met interim leader Muhammad Yunus and other senior officials. Guterres praised Yunus and his government for their efforts to restore democracy following the ouster of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina last year.

The praise was a welcome boost for an increasingly beleaguered government in Dhaka as economic stress and law and order challenges mount, putting more pressure on the government to deliver results and announce a timeline for elections.

Guterres also visited the town of Cox’s Bazar, which hosts hundreds of thousands of Rohingya refugees who have fled neighboring Myanmar since 2017. Guterres made a pitch for more global support for the Rohingya—well-timed, given rising concerns about cuts to humanitarian aid. In recent months, the insurgent Arakan Army has taken control of the Bangladesh-Myanmar border.

The situation in Myanmar risks intensifying border instability and worsening conditions for the Rohingya, which could prompt more refugees to enter Bangladesh. Guterres called for a solution that enables the peaceful relocation of these refugees back to Myanmar. Yunus has tried to convince global capitals to take in some Rohingya refugees but has had limited success.

FP’s Most Read This Week

Under the Radar

As Trump passes the 50-day mark in his second term, his administration is mulling plans to impose full or partial travel bans on citizens from several dozen countries. According to New York Times and Reuters reporting, Bhutan might be on the list, along with Afghanistan and Pakistan.

This has surprised observers, as Bhutan is relatively stable, with few known security threats to the United States. The current U.S. State Department travel advisory for the country is Level 1, the lowest category. Bhutan doesn’t have formal relations with the United States, but the ties between the two countries are nonetheless friendly.

According to the Bhutanese, a local outlet, Bhutan may be included on the list because of the country’s high visa overstay rates in the United States. However, the article notes that some countries with higher overstay rates, such as Bangladesh, are not included on the travel ban list.

It’s unclear if Bhutan will end up on the list in the end, as the policy has not been finalized.

The post Is Modi Turning Over a New Leaf With China? appeared first on Foreign Policy.