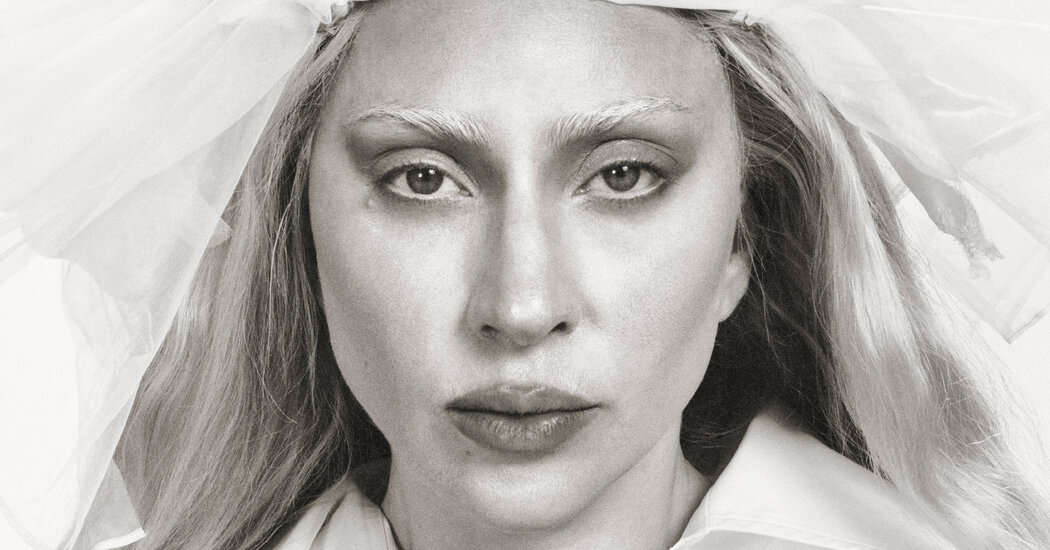

Over the course of her long career, Lady Gaga has proved herself to be one of music’s great shape-shifters. She has gone from the dance pop of her earliest albums, like “The Fame” (2008), to the rockier “Born This Way” (2011), to country-inflected sounds on “Joanne” (2016), to singing American Songbook standards alongside her friend Tony Bennett. Despite surely making her record label nervous a few times, the mercurial nature of Lady Gaga’s gift has come at no discernible cost to her career. She is one of only three solo artists — Michael and Janet Jackson being the others — to have hit No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 singles chart multiple times across three different decades. She has also earned 14 Grammy Awards, including one earlier this year for her duet with Bruno Mars, “Die With a Smile.”

All that success made it especially intriguing to learn that her new album, “Mayhem,” which arrived this week, would be a return to the pop sounds of her early work. A step into familiar territory is a curious one for someone so steadfastly set on surprise. Was she hoping to capture some nostalgia? Looking for back-to-basics rejuvenation? Or could it be that making a “classic-sounding” Lady Gaga album was going to be some sort of meta examination of her own music and image?

As she explained it when we spoke in February, the answer is, in a way, all of the above. At 38 years old, and after some time lost to fibromyalgia and personal trauma, Gaga finally felt ready to reclaim a sound that belonged to her. She also, thanks in no small part to her fiancé, the entrepreneur Michael Polansky, felt supported enough to do it. Which is proof that, for a world-famous pop star anyway, a little normalcy can be the most productive change of all.

In an announcement for “Mayhem,” you referred to your “fear” of going back to the pop music that your earliest fans loved. Why were you scared of that? You know, I made my artistic way living on the Lower East Side starting around 17 years old, and worked the New York music scene as much as I could. Ultimately that landed me into making “The Fame,” my first studio album. That music came out of the culture of people that I was living with at the time. I was surrounded by musicians, photographers, club promoters, people that lived and breathed art. It was a community of support, and one of the reasons I was afraid was I was so far away now from that community. It also felt like maybe I would just be recycling something that I had done before. But ultimately I decided that I really wanted to do it and that this sonic style and aesthetic really did belong to me.

How do you characterize that sound? My sound is an amalgamation of the music that helped me fall in love with music. So it’s got classic rock in it, disco, electronic music, ’80s synth. It’s sort of like picking and choosing my favorite fragments of songs that I loved throughout my childhood. It is everything I love about music but all in one place. I didn’t always do that. Sometimes, in my records, I decided, OK, I’m going to make my version of a country record.

“Joanne.” Right. But the way that I was bridled to think about women in music — they talk to you a lot about your look and what the aesthetic is for the album and the “brand” of music. That started to affect how I made music.

When you say you felt “bridled,” what do you mean? It’s the way they talk to you about who you are. When I moved to Hollywood and was playing my music for Interscope for the first time, they had conversations about, what’s your look going to be? And you’re thinking, It’s going to be me. How are you going to dress? Well, I’m going to wear what I usually wear when I’m onstage. They introduce you to start thinking about it as a business as opposed to a performance.

Were there ways in which you were just treated as a commodity? Yes. I always feel nervous to talk about this because I’m extremely grateful for the career I’ve had. I also can say with a lot of honesty that, being in the music industry since I was a teenager, some of it is how much you are willing to give away. Things like eating at the dinner table with your family, it never happens. Being in a room by yourself never happens. Being carted around, told where to go. I’m sure that must sound peculiar to people because they see you on top of the world and they think you’re the boss, but as a woman in music, I would say it took me 20 years to become the boss. I am now, and that’s thanks to having wonderful people around me, including my partner, Michael. I wrestle with this, how to talk about it. Because I want to acknowledge all the blessings in my life while also speaking up for women in this industry. There are no laws around who can be a producer, and they’re not vetted by anyone. So when you’re 17 years old and you are invited into a studio, you have no protection. You don’t know where you’re going. You may not even have an adult in the room with you other than the person that you’re working with. It’s not the safest industry.

I’m curious what you made of Chappell Roan’s speech at the Grammys, where she talked about the ways in which the record labels are not supporting the artists with health care or a living wage? I think Chappell Roan is speaking the truth, and she is courageous to do so. I look at what she’s been doing and saying and think, Man, I should have stood up for myself more when I was younger. I think a woman speaking their mind is a powerful thing, and I was really happy she did that.

Your partner, Michael, is an executive producer on the album. What impact did he have on the music? Michael was in the studio every day with me. He oversaw the whole process of making the record, completing it, helping me to shape the sound of the record creatively. It was an amazing thing to do with your partner, because when I start to doubt myself, there is nobody that’s going to call me on it better than he is.

Do you have an example? Yeah, actually. There was one point where I almost turned the whole album into a grunge record.

He talked you out of that? I would have listened to that! There’s plenty of grunge on the album. It was right after I did “Perfect Celebrity,” that song, and I was like, “Oh, everything should be this,” and he said, but there’s so much other amazing music that you’ve made, and it’s all you. You don’t have to try to be something. I thought that was really astute, and I was happy it happened because often I will run with my crazy idea and then sometimes regret that.

I could imagine that relationships are tricky in your position because you might have questions about whether someone’s feelings are genuine, or if they want to be with you or their idea of you. How did you realize that Michael was genuine? From the moment that I met Michael, he had the most warm and kind disposition of maybe anyone that I had met in my whole life. Yes, he was impressive, but the thing I cared about the most was he wanted to know about my family. [Pause.] I’m sorry I’m crying.

No, it’s OK. I guess what I’m trying to say is, I knew Michael was genuine because he wanted to be my friend. He didn’t want to do any of the things that the other people wanted to do. He wanted to take walks with me. He took me rock climbing. I also have a pain condition, but he had this belief that I could get better, and he inspired me to have more hope about it. So, yeah, I guess I know Michael is genuine because he’s my friend.

I hope this doesn’t sound trite: I’m glad you found that. Thank you. I’m glad I found it, too. It was really hard not having it. It’s not a good feeling to have so much trouble making friends. Being actually friends with somebody is a very specific thing. You can sit in a room together and not talk. You can take long walks and talk about your family. You can obsess over a new recipe and make it. I don’t think it should be transactional, but I was around a lot of that all the time. So it’s a big blessing that I met someone that was not like that. It’s a new world for me.

That feeling of contentment might be one that artists can mistrust, because of the idea that great art is created under tense circumstances. We don’t have as many cultural legends about when happy artists make great art. I think that romanticizing sick artists perpetuates this thing that’s supernegative, especially for women. I want women to feel like they can be healthy and be happy, that we will celebrate them in their health. I feel grateful that I’m still here, because my life could have been very different. Over five years ago I was in a really dark place, and I wouldn’t say I made my best music during that time.

If you look at the history of pop music, there aren’t a ton of people who, as they get older, don’t end up becoming legacy acts or chasing trends. But are there people who forged a trail that looks comfortable to go down? Tony Bennett forged the trail that means the most to me. Tony always used to tell me, “Just stick with quality, kid.” That made me feel so happy and safe: that if I leaned into my artistry, I didn’t have to be afraid. That’s a lot of what this album is for me. I just leaned into my musicianship. I told myself whatever happens over the next 20 years, 30 years of your career, you’re always going to be a musician, and you’re always going to be an artist, and you can always work at it. I’ve definitely arrived at a place where achieving world domination into my 90s is not what makes me tick. This idea of winning, I don’t know if that’s synonymous with great music.

Might you have a different attitude if you hadn’t already won? I ask myself that question pretty often, actually. Like, how would I look at this differently? Am I thinking about this the right way? There’s just noise sometimes, and pressure. But the person that puts the most pressure on me is me. Sometimes I have to warn myself to do something at 70 percent because 100 is going to bang you up. I’m getting ready for Coachella, and I’m so, so excited, but I’ve definitely lost sleep a whole bunch of nights, and it’s because I want to do a great job. If there’s a time and a date where you can make the public smile, from 11 p.m. to 1 in the morning on this day, I want to make it happen.

At the Grammys, I think you were the only musician who said something in your acceptance speech explicitly in support of trans rights. Is there a political aspect to your mission as an artist in 2025? I’m not interested in being famous to stand for nothing. It’s a privilege to stand with people that are so amazing. I’m in awe of the trans community, and I’m in awe of the L.G.B.T.Q.+ community, and I have been since I was really young. If you win an award, you have 45 seconds to speak while the world is listening, and I wanted to say something that matters to the people that I care about. I’m not a trans person, but I try to imagine what it would feel like to wake up living in America and living in the world right now. Being supportive, being kind, we can’t whisper about these things. We have to say them out loud.

Kindness is hugely underrated. Do you have thoughts about how we might encourage it? I’m not an authority on kindness, but my thoughts are it’s not just about what you put on your Instagram. It’s about how you live your life. It’s about how you have conversations with people, who you make an effort to be friends with, to understand the stories of others. How do you make sure that systems are operating in inclusive ways and ways that celebrate people? It can’t just be when people are watching. You’ve got to be kind all the time.

There’s a great story — maybe apocryphal — that I read about you: When you were very young, you were playing at a bar in Manhattan, and there were some loud frat boys who weren’t paying attention. The way you got them to pay attention was you stripped down to your underwear and performed, and that moment showed you new possibilities for the kind of artist that you could be, that there could be a performance-art aspect to what you do. I’m curious if you’ve had any artistic epiphanies more recently? I was definitely somewhat of an exhibitionist as a young artist. I was also a big fan of shock art and studied it a lot when I was younger. I thought Spencer Tunick’s art was really interesting. I thought Sandy Skoglund’s art was really interesting, Marina Abramovic’s art. But where I’ve arrived now is I feel a lot more at ease with my artistry and also comfortable creating some boundaries around how to prioritize things. I for a while prioritized fashion and red carpets; it’s a part of your art, but it’s also a part of the job. Now I’ve prioritized that less and I’ll spend much more of my day playing piano and singing, writing songs, producing. I don’t mean that in disrespect to the art of glam, because red carpets for me were a place to be artistic during my career.

They were a canvas. They really were a canvas. There is some freedom in going like, OK, I have a red carpet later, but instead of spending weeks planning for this, I’m going to make another album or I’m going to work on a new project. The reason I’m bringing this up is because I felt pulled in so many different directions over the last 20 years, but the place that I feel the most happy is working on my own art, and I love singing for people. The image piece of it, I prefer that more when it’s about artistry and not just about beauty. There’s lots of corsets and dieting and makeup and pressure, and then there’s the best-dressed list — it’s its own thing, and I don’t mean that to be disrespectful of it. I partake in it, but that’s more challenging for me than making my record. It feels further away from who I am.

When you were interested in playing with artifice and trying on different personas, was that ever psychologically destabilizing? Absolutely. At a certain point, I just completely lost touch with reality. I was falling so deeply into the fantasy of my artwork and my stage persona that I lost touch. I wouldn’t say that falling deeper into a life of being a tortured character was good for anything.

It worked, though. I suppose, in a way. I think there are some people that really liked that side of me, but I didn’t like that side of me, and I was really unhappy, and I feel like I have myself in order now. I went back downtown to a bar that I used to go to all the time last week. I’d go in the middle of the day, and I would order a whiskey and a beer. That’s where my friends were. That’s where my artist community was. I used to visit, and I used to feel really sad, like I was far away from the person that I was when I was living down there. But this last time that I went, I felt like the old me.

Do you have any skepticism internally about whether the person you are now is just another persona? No, but I know why you’re asking me that.

“I am authentic now” is a thing that people do. I’m sure that does happen. Let’s put it this way: I was authentic before. That was authentically me. I just was authentically splitting off into different personalities all the time. Now, who I would be at dinner with you is who I would be in this interview. I guess authenticity is subjective. I just feel like I more easily can hold it all.

Earlier you alluded to a period five or so years ago when your mental health was not in a great place. Are you able to tell me more about what was going on then? Yeah, I mean, I had psychosis. I was not deeply in touch with reality for a while. It took me out of life in a big way, and after a lot of years of hard work I got myself back. It was a hard time, and it was actually really special when I met my partner because when I met Michael, I was in a much better place, but I remember him saying to me, pretty early on, “I know you could be a lot happier than you are.” It was really hard for me to hear him say that because I didn’t want him to think that of me. I wanted him to think I was like this happy, totally together person. But it’s something that I have found increasingly harder to talk about. I hate feeling defined by it. It felt like something I felt ashamed of. But I don’t think that we should feel ashamed if we go through times like that. I mostly just wish to say, it can get better. It did for me, and I’m grateful for that.

How did you turn it around? It goes back to what you were saying about playing characters earlier in my career. I had to figure out a way to integrate myself fully with my stage persona and kind of inhabit Lady Gaga’s boss energy in my everyday life but in an empowered way, and make sense of maybe two things that don’t make a ton of sense. I’d like to think that I’m a kind person, but there’s a ferociousness and a hardness and an intensity that I have onstage as a performer. So I had to learn how to hold those two things and have them not be at war with each other. I’ve learned to not pour gasoline on it. I used to like more chaos, just living life on the edge constantly. I’m now proud to be much more boring.

Before the interview started, we were making small talk, and I mentioned my kids. You, in a wistful way, said, “I would love to have kids one day.” Do you have any apprehension about having kids and still being able to be Lady Gaga? No, I don’t. I’m excited to be a mom. I used to have a lot of apprehension about it. The thing that’s the most important to me is to not force my children to live a life that they are not choosing. So the more that we can give them space to discover who they are on their own, that’s the thing that I believe in the most. If our children only understand Mommy’s job, that’s a very narrow view of life. There’s so much in the world, and I want them to be able to choose for themselves who they want to be. I’m also kind of at war with myself sometimes as I get ready to, hopefully, become a mom soon. Like, today is wonderful, but the whole day has revolved around me. There’s an incredible amount of narcissism in this. How do I live a life where I’m passionate about my art while also making more space for other things?

I suspect the only answer is living it. Yeah, through living it. Like, “Mayhem” coming out, it’s kind of like my birthday. But maybe there’s a time for it to be someone else’s holiday.

This interview has been edited and condensed from two conversations. Listen to and follow “The Interview” on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, iHeartRadio, Amazon Music or the New York Times Audio app.

The post Lady Gaga’s Latest Experiment? Happiness. appeared first on New York Times.