Amid all the anxiety in Europe over Donald Trump’s return as U.S. president, essential differences have emerged between various countries’ approaches to managing what promises to be a tumultuous relationship. These cleavages will make it harder for Europe to define and defend a single common policy on the United States. But the fact that there is more than one European approach to transatlantic relations may help European security in the end. The best hope is that a smaller group of hardheaded, defense-minded countries—Poland, the Nordic countries, and the Baltic states, perhaps joined by Britain—will promote European security interests vis-à-vis Trump 2.0.

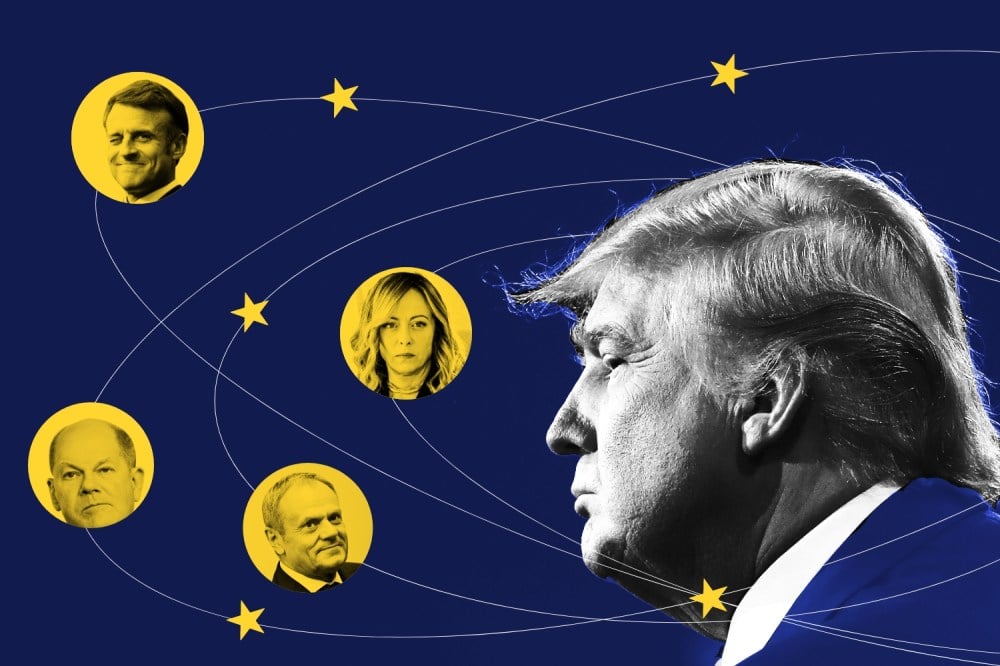

There are four distinct groups of European countries in terms of their relations with Trump. First, there are the enthusiasts: a small handful of right-wing populist leaders who share his worldview and mimic his style, such as Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, and Slovakian Prime Minister Robert Fico. Second, there are the engagers: Poland, the Nordic countries, and the Baltic states, most of which rank among NATO’s highest per-capita spenders on defense and are making a pragmatic effort to build a functioning relationship. Third, there are the moralizers, such as outgoing German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, whose relationship with Trump is poisoned by mutual contempt. All by themselves in a fourth category are the French: opportunists who, like President Emmanuel Macron, see transatlantic acrimony under Trump as the chance for Paris to claim leadership of a post-American Europe.

Amid all the anxiety in Europe over Donald Trump’s return as U.S. president, essential differences have emerged between various countries’ approaches to managing what promises to be a tumultuous relationship. These cleavages will make it harder for Europe to define and defend a single common policy on the United States. But the fact that there is more than one European approach to transatlantic relations may help European security in the end. The best hope is that a smaller group of hardheaded, defense-minded countries—Poland, the Nordic countries, and the Baltic states, perhaps joined by Britain—will promote European security interests vis-à-vis Trump 2.0.

There are four distinct groups of European countries in terms of their relations with Trump. First, there are the enthusiasts: a small handful of right-wing populist leaders who share his worldview and mimic his style, such as Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, and Slovakian Prime Minister Robert Fico. Second, there are the engagers: Poland, the Nordic countries, and the Baltic states, most of which rank among NATO’s highest per-capita spenders on defense and are making a pragmatic effort to build a functioning relationship. Third, there are the moralizers, such as outgoing German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, whose relationship with Trump is poisoned by mutual contempt. All by themselves in a fourth category are the French: opportunists who, like President Emmanuel Macron, see transatlantic acrimony under Trump as the chance for Paris to claim leadership of a post-American Europe.

It is no coincidence that the first European leaders to pay their respects to Trump at his Mar-a-Lago residence in Florida following his election victory were the most prominent European Trumpists—Orban and Meloni—and that the guest list at Trump’s inauguration included many radical right-wing populists. Trump’s affinity to these politicians obviously draws on an ideological closeness, including shared illiberal or anti-liberal views on democracy, migration, and cultural values, as well as an admiration for authoritarian strongmen. And Trump loves personal flattery, which comes more sincerely from fellow populists than mainstream European leaders.

Ideological closeness, however, is unlikely to provide a solid basis for the relationship. Trump’s foreign policy pursues naked self-interest, and U.S. interests do not necessarily align with those of the European populists. Democracies have traditionally been tied together by shared values and similar political systems, predisposing them to value-based cooperation in foreign policy. Autocrats tend to be less enthusiastic about alliances and more interest-based in their external affairs. Trump leads a country that is still democratic, but his foreign policy seems to reject a values-based agenda. It is not clear what Orban, for example, can offer a transactionalist like Trump—or how far mutual personal admiration will get him. Orban has gone to great lengths in building closer ties with China, but from the U.S. perspective, Beijing is the main threat to Washington’s superior position on the global stage.

Unlike Orban and despite the fascist roots of her party, the pragmatic Meloni has achieved a powerful position in Europe. Thus, her relationship with Trump could be more broadly important for Europe. Rome seems to be investing heavily in a transactional approach, such as ongoing negotiations with Elon Musk’s SpaceX over a possible $1.5 billion deal for secure communications services, despite Italian concerns about risks to national sovereignty. But the fact that Italy spends less than 1.5 percent of GDP on defense will not win Meloni any favors in Washington.

Even if Europe’s populists were able to extract benefits from Trump, it’s not clear how that would have much impact on the rest of the continent. Right-wing populist parties have struggled to cooperate and build coalitions across country borders in spite of their ideological closeness. Some have opted for cooperation with mainstream parties, while others trust in the appeal of more radical positions among their electorates. Photo opportunities aside, the reality is that each basically stands on its own.

This takes us to the second group. The northern engagers have a hard-nosed view of security, a strategic preference for solid transatlantic relations, and the willingness to proactively appeal to Trump’s transactionalism. They are the most exposed to Russia and the most concerned about European underspending on defense, which increases both the likelihood of Russian aggression and the risk that the United States will abandon allies seen as unwilling to provide for their own security. The northern states have tried to end this vicious cycle, knowing that the more they spend on defense, the more likely the United States is to stay in the region and help deter Russia. Their advice was recently summarized by Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk: “Instead of reading between the lines of President Trump, let’s do our homework.” Poland, Estonia, and Lithuania have already endorsed Trump’s new target for European countries to spend 5 percent of GDP on defense. But leaders like Tusk will also need to persuade Trump to refrain from statements or actions that could increase the risk of a Russian attack against a NATO country, possibly due to miscalculation in the Kremlin about how the alliance might respond.

In the spirit of dealmaking, the Nordic countries have been keen to offer concrete benefits to their biggest and most important ally. Trump’s strategic interest in the Arctic region as an arena of great-power competition might help to find mutually beneficial projects. Denmark has been startled by Trump’s threatening rhetoric regarding Greenland but has reacted with restraint, welcoming closer cooperation and more U.S. investment while rejecting Trump’s offer to buy the island. Finland, a leading producer of icebreakers, is pursuing cooperation with the United States to build and maintain such ships. Ukraine has adopted a similar approach of beneficial deals and is preparing an agreement with Trump regarding its large reserves of critical minerals, such as lithium, natural gas, and titanium. The limits of such pragmatism have already been pushed hard by Trump’s bullying over Greenland. Denmark’s weak military and long record of underspending on defense—which hit the NATO minimum of 2 percent of GDP only in 2024—has made it vulnerable to U.S. claims that it is not able to protect Greenland.

The third group—moralizers who express what they see as the high ground vis-à-vis Trump—is most clearly represented by Germany. During Trump’s first presidency, then-German Chancellor Angela Merkel was hailed as the new “leader of the free world.” More recently, when Trump expressed his desire to gain control of Greenland, it was Scholz who jumped to condemn him, saying, “The principle of the inviolability of borders applies to every country, regardless of whether it lies to the east of us or the west, and every state must keep to it, regardless of whether it is a small country or a very powerful state.” Coming from Scholz, this is vacuous moralizing; Berlin has pointedly refused to take leadership in pushing back Russia, whose war against Ukraine breaks many more of the international norms Scholz claims to uphold. Moralizing has little practical value or credibility if it is not backed up with readiness to defend one’s norms and values against the aggressor, using force when necessary. Still, Berlin’s sentiment is shared by many politicians and commentators in Europe and the United States as Trump’s disregard for international institutions, norms, and the rules-based order sends shockwaves across liberal elites.

Fourth, France has a long record of opportunistically viewing every crisis hitting Europe as vindication of its agenda of European strategic autonomy—under French leadership, bien sur, and usually directed against Washington. There is certainly a strategic case to be made for Europe to be less dependent on other powers, including the United States. However, what makes the French look so opportunistic is their Gaullist desire to lead Europe and use the European Union as a vehicle for French interests. At the same time, Paris has been unwilling to give up its own autonomy (for example, by turning the French seat in the United Nations Security Council into a common EU seat) or give due consideration to the interests of other Europeans. For example, until recently, France insisted on channeling EU defense funds only to European defense firms—meaning, in large part, French ones—which undermined the interest of northern and Eastern Europeans in keeping Washington engaged in their security, including through purchases of U.S. arms. Furthermore, European industry lacks the capacity to meet Europe’s vast and urgent defense needs. From the viewpoint of countries facing an existential threat from Russia, it is unwise to make big statements about European autonomy while Europe so obviously lacks the capabilities needed to defend itself without a major U.S. contribution.

All of this is not to deny that the French aspiration to lead Europe can serve broader European interests. Macron’s meeting with Trump and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky in Paris last December is a good example. The French have shown they have the diplomatic skill to flatter Trump while also signaling readiness to defend their interests. Europe needs more of this kind of engagement.

Trump 2.0 could be a disaster for Europe for many reasons. He may strike a bad deal with Russia in regard to Ukraine, disrupt global trade, turn European states against each other, and heighten turmoil by empowering right-wing parties. Even Trump’s best allies in Europe should be prepared to push back against his most egregious statements, such as his refusal to rule out military force to gain control of Greenland.

For the time being, the transatlantic alliance remains Europe’s best hope of getting through an era of turbulence—where the old global order no longer works and democracies struggle to shape a new one to protect their interests and values. Becoming more dependent on China or letting Russia reshape Europe’s security order are not viable options. Europeans will have to deal with Trump, keep NATO alive, strengthen their own agency, and build a military force to be reckoned with. Pragmatic engagement of Trump by northern Europeans, coupled with their strong defense commitments, might the most promising way to manage the transatlantic relationship in the coming years. But there is a real danger that the Trump administration will divide and rule a Europe that is too weak to stand on its own feet.

The post Europe’s Four Different Ways of Handling Trump appeared first on Foreign Policy.