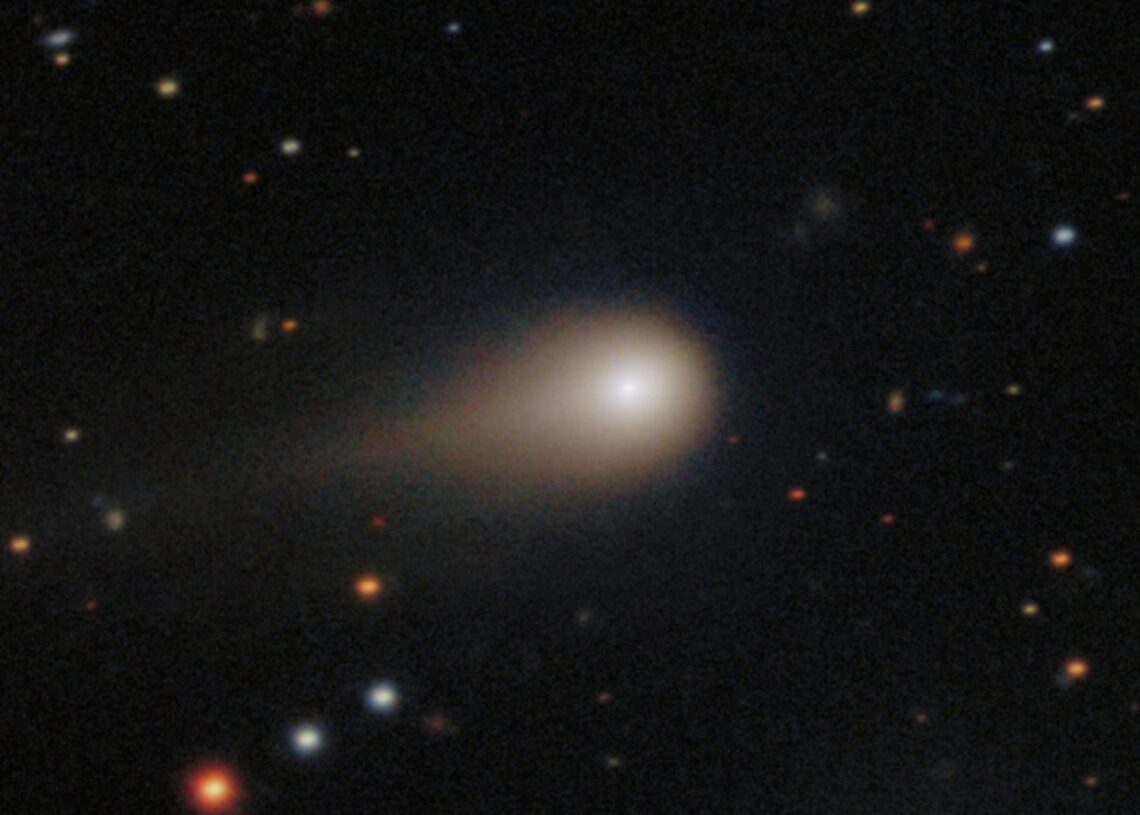

3I/ATLAS, the bizarre interstellar comet that has befuddled scientists for months, is finally starting to make some sense.

As it gets closer and closer to us, researchers around the world are finally getting a chance to better understand what this thing even is. Sorry, Harvard astrophysicist Avi Loeb, but it is looking less and less likely that it’s some kind of alien artifact.

Instead, it’s a cool comet that has added another cool thing to his repertoire of cool and unusual behavior: ice volcano eruptions. Not only does it sound cool, but it’s also exactly what it sounds like.

Interstellar object 3I/ATLAS started shedding ice and dust as it got closer to our sun. When it entered its perihelion phase, the phase in which an object is the closest it can get to the sun, astronomers watched the thing blast out jets of gas and debris so dramatic that the comet formed both a normal tail and an anti-tail at the same time.

3I/ATLAS Is Covered in Ice Volcanoes, New Images Suggest

Researchers studying the gaseous expulsion with the Joan Oró Telescope in Spain think those jets were actually the surface of 3I/ATLAS popping off via cryovolcanoes. In other words, ice volcanoes. Volcanoes that shoot ice are like the work of a hacky science fiction author made real.

The findings, which have not yet been peer-reviewed, were published on arXiv. According to study lead Josep Trigo-Rodríguez, the comet’s surface chemistry looks similar to that of the trans-Neptunian objects lurking in the Kuiper Belt.

The team suspects the activity may be driven by carbon dioxide ice buried within the comet reacting with metals such as nickel and iron sulfides. As the Sun heats the object, the carbon dioxide sublimates and chemically oxidizes those metals, generating enough internal pressure to shoot jets of icy vapor into space.

While we’ve learned a lot in the past few weeks about this mysterious interstellar visitor, we’re running out of time to learn as much as we can, as there are still plenty of mysteries to unravel.

After it whizzes by the Earth later this month, it will head toward Jupiter in 2026 before venturing back out into interstellar space.

The post Ice Volcanoes Are Erupting on 3I/ATLAS, New Images Suggest appeared first on VICE.