“What’s next?” As a New York Times obituary writer, it’s a question I’ve never dared ask.

While interviewing prominent people as I craft in-depth profiles in advance of their deaths, I don’t want to miss the story. But the answer is, nobody knows for sure.

A news obituary is a biography about a life that begins at the end. It mentions death only once; it never suggests what, if anything, follows — a prospect so many people have contemplated for thousands of years, whether what they hope or think comes next is heaven or reincarnation or an oblivion equivalent to the one we were in before we were born.

I was reminded of this gap in my reporting by the death in ancient Egypt of a man named Ankhmerwer more than two millenniums ago.

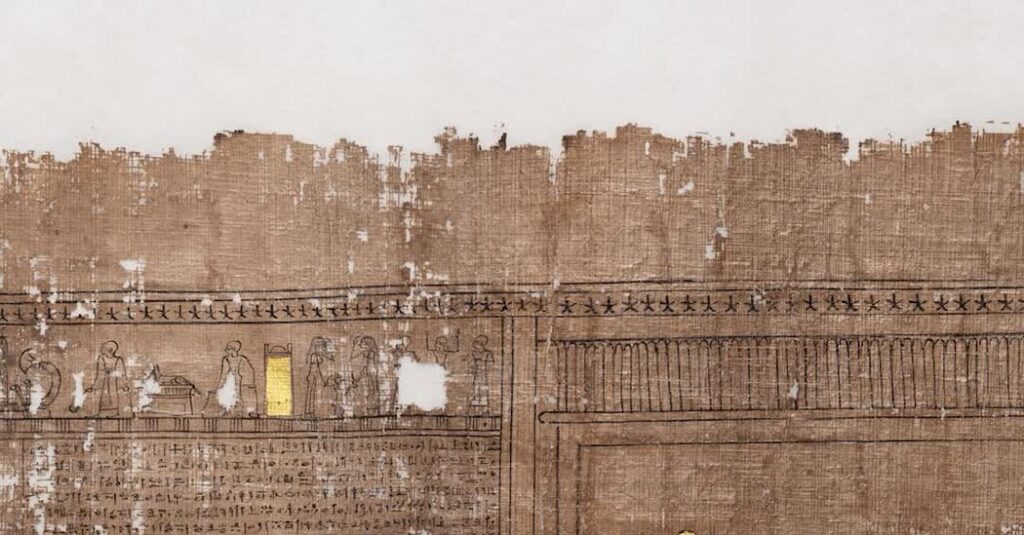

There were no newspapers or obituary pages back then. But Ankhmerwer’s death did not go unrecorded. It was memorialized on a rare, intact, gold-accented funerary scroll 21 feet long, known as a Book of the Dead. Those types of books predate The Times’s obit pages by about 3,000 years. Ankhmerwer’s scroll, gold amulets, reed pens and other ancient artifacts went on public display last month, perhaps for the first time ever, curators say, in the Brooklyn Museum’s Egyptian galleries, for an exhibition titled “Unrolling Eternity: The Brooklyn Books of the Dead.”

The scroll was believed to have been found in Ankhmerwer’s tomb near Memphis in Lower Egypt (so called because, while in the north, it abuts the lower Nile) early in the 19th century by Henry Abbott, a British doctor.

His collection of some 1,200 artifacts was purchased by the New-York Historical Society and later transferred to the Brooklyn Museum. For the first time, it is on permanent exhibition there after being stashed away for some 150 years. It has undergone a three-year restoration by the conservators Ahmed Tarek and Josephine Jenks thanks to a grant to the museum from the Bank of America.

How does the scroll compare to the way we cover deaths today?

To begin with, a Book of the Dead is a misnomer, applied by 19th-century Western scholars. A more accurate translation of the title would be “Spells of Coming Forth by Day.” Unlike obituaries, they aren’t biographies. They aren’t even books. And, they’re not of the dead. They’re for the dead — a chapter-by-chapter encyclopedia of self-selected incantations and magic spells from master indexes compiled by Egyptian priests.

Ankhmerwer’s includes 162 of them.

He thought he knew what was next and came prepared. The rolled-up scroll he took with him, probably in his sarcophagus when he died, is a practical guidebook, a road map to the underworld, helping souls avoid the parlous beasts (illustrated) and other dangers in their quest for an idealized eternity, which for the ancient Egyptians meant a reunion with the gods in the Field of Reeds reserved for righteous souls.

We clutch at straws in our own ways. Our obsession with what comes next explains why so many people, knowing that I write obituaries, slip me their résumés and C.V.s. They’re concerned about posterity in the paper of record — about their reputations, about how they will be judged by future generations, a concern that helps distinguish humans from other species. It’s why George Washington in “Hamilton” sings, “You have no control who lives, who dies, who tells your story.”

It’s also a question that has perpetuated religion in one form or another. Even skeptics of divine providence cover their bets. I quoted the columnist Charles Krauthammer in his obituary as saying, “I don’t believe in God, but I fear him greatly.” In a 1971 book, Woody Allen cracked wise: “I don’t believe in an afterlife, although I am bringing a change of underwear.”

Paid death notices often say that people “passed” (but at The Times, to avoid euphemisms, only quarterbacks do) — taking for granted we know where they went. People place “in memoriam’ advertisements addressed to relatives on the anniversaries of their deaths. Disney theme parks’ secret staff protocols even include what has been called a “white alert” code to warn when a guest seeking perpetuity in the Magic Kingdom attempts to scatter human ashes in the park.

Not to demean an ancient ritual, but my communing with the Book of the Dead at the Brooklyn Museum improbably evoked an episode of Larry David’s “Curb Your Enthusiasm.” The Davids are committed to renewing their marriage vows until Larry’s TV wife, Cheryl, presents Larry with a draft:

Cheryl: “We’ll love each other throughout this lifetime, but after death through all eternity.”

Larry: “You mean this is … this is continuing into the afterlife? I thought this was over at death. I didn’t know we went into eternity together. Isn’t that what it said in … ‘’til death do us part.’ I guess I had a different plan for eternity. I thought, I thought I’d be single again.”

If one derivation of “obituary” is the Latin word “obire,” which suggests a rite of passage (a euphemism if there ever was one), the word still connotes an ending. Whatever happens next, if anything, is left for biographers to assess, clergy to warn against or spiritualists to invoke in seances.

The Book of the Dead represents a beginning of sorts. It’s all about the future. The scrolls were typically commissioned and approved by the subjects or their families beforehand (akin to the obituaries of famous people that we prepare in advance — but based on our news judgment, not a commission, and without their approval).

While it is generally more prescriptive than descriptive, it may mention the departed’s divinely inspired human deeds, but the pre-dead are also prepped to recite in their underworld odyssey what constitutes a negative confession: They must enumerate before a panel of judges the sins that they did not commit during their lifetimes.

The scroll provides some physical evidence about who Ankhmerwer was, his age and how he ranked in society. He wasn’t poor. Three scribes probably spent several months brushing the cursive hieroglyphics on fibrous pith from papyrus plants to produce his scroll, distinguished by its gilded accents and the fact that it is displayed unfurled, from beginning to end. His scroll was custom made; other fill-in-the-blanks versions could be bought off the rack, with the deceased’s name added later.

But the scroll reveals little about his background or accomplishments (he might have been too young to have achieved much). He was the son of Taneferher, who was “beautiful of face”; someone of the same name — not necessarily his mother — was a musician and a priestess. We don’t learn enough about Ankhmerwer to know whether he would have even merited a Times obituary.

The scroll measures 21 feet. That’s considerably longer than any article that I have ever written. (And my Times obits were never gilded.)

The longest obituary published in The Times was Pope John Paul II’s, in 2005, by Robert D. McFadden. Its 13,870 words voluminously reviewed his record at the Vatican, of course, but also revealed that he was fluent in seven languages, was a guitarist and played goalie on his high school soccer team and was the first non-Italian pontiff in 455 years.

That’s a lot more than we know, even now, about Ankhmerwer.

All in all, I’d rather be an obituarist than a stenographic scribe whose Book of the Dead got entombed in a sarcophagus, not to be disinterred for thousands of years, if ever, no matter how artfully crafted or well received by the subject who commissioned it.

“I’m willing to bet,” said Yekaterina Barbash, the Brooklyn Museum’s curator of Egyptian, Classical, and Ancient Near Eastern Art, “they didn’t expect anyone else to read it.”

Unrolling Eternity: The Brooklyn Books of the Dead

Ongoing, Brooklyn Museum, 200 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn; (718) 638.5000; brooklynmuseum.org.

Sam Roberts is an obituaries reporter for The Times, writing mini-biographies about the lives of remarkable people.

The post Writing an Ancient Egyptian Afterlife, in 21 Feet of Scroll appeared first on New York Times.