In 1888, not long after Vincent van Gogh moved to Arles, a picturesque city built on Roman ruins in the south of France, he wrote to tell a friend, the Parisian painter Émile Bernard, about his new lodgings.

“I’ve rented a house painted yellow outside, whitewashed inside, in the full sun,” van Gogh wrote, adding a description of his view: “The town is surrounded by vast meadows decked with innumerable buttercups — a yellow sea.”

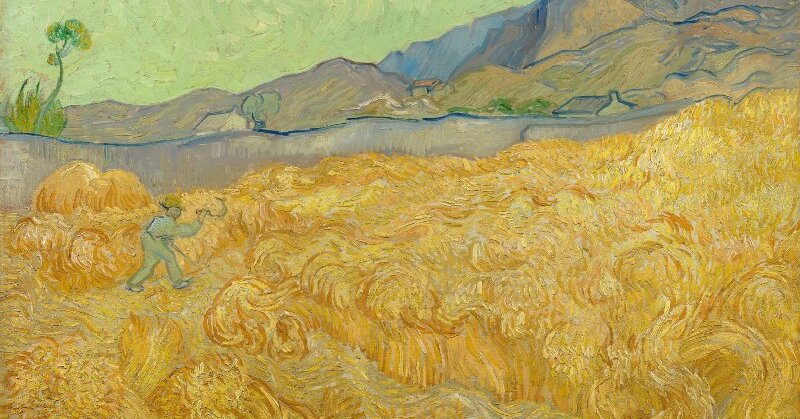

Living in a yellow house amid this “yellow sea,” van Gogh turned again and again to the color to create some of his most recognizable canvases: golden wheat fields under a blazing sun, the butterscotch-colored canopy of a cafe terrace at night, and a flaxen vase filled with sunflowers.

Pablo Picasso had his Blue Period in the early 1900s, a melancholic phase in shades of blue. Van Gogh’s “yellow period,” as one might call it, reflected the warmth of the Provençal sun, but also the artist’s feeling of consolation, hope and optimism during that brief period of his career.

He used it so much in his Arles years — a time when he was at the height of his artistic powers — that he became forever associated with the color.

“Yellow. Beyond Van Gogh’s Color,” an exhibition at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam that runs until May 17, makes the hue into an organizing principle. The color connects the 19th-century postimpressionist not only to other artists such as Paul Signac, Kazimir Malevich and J.M.W. Turner, but also to a lady’s parasol, a ball gown, and two immersive installations by the Danish artist Olafur Eliasson.

The curators take van Gogh’s 1889 “Sunflowers” as a starting point to explore the color’s shifting meaning for artists.

“It’s a journey,” said Ann Blokland, one of the show’s two curators. “For van Gogh’s time, it was a color of modernity, of spirituality and of color theory. But we want you to be able to wander through the exhibition to make your own associations.”

Color theory was a preoccupation of a number of fin de siècle artists, including Wassily Kandinsky and Hilma af Klint, who believed that certain colors had spiritual resonances or symbolic meanings and that certain combinations would stir emotional vibrations in the viewer.

Kandinsky described yellow as having the sound of a “blaring trumpet,” and he created a musical theater piece called “The Yellow Sound” to express the idea. It was not performed in the artist’s lifetime; the Amsterdam show presents a video a clip of a 1974 production, with music by Alfred Schnittke.

The curators have also included some newly composed attempts by Amsterdam conservatory students to capture the essence of yellow in sound, and perfumes that suggest the color with scents including vanilla, bergamot and patchouli, which visitors can sniff from glass decanters.

This sensory approach extends to two featured works by the Berlin-based artist Olafur Eliasson, who is know for light installations like “The Weather Project,” a site-specific 2003 installation made for the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern in London, in which a bright yellow orb created the illusion of a sun.

Blokland and her co-curator, Edwin Becker, offered Eliasson an entire floor of the museum for two large installations: his 2006 fluorescent light sculpture, “Who Is Afraid Yellow Flower Ball”; and “Color Experiment No. 78,” from 2015, a series of 72 circular monochromatic paintings that seem to change color when illuminated by yellow lights.

This “mathematical” interest in color theory and technique links Eliasson with van Gogh, Blokland said.

Van Gogh played with color combinations — favoring contrasts like yellow and blue, and yellow with purple — but not always on his canvas or palette. Before picking up the brush, he gathered strands of colored wool into balls to see how the tones looked when combined. A lacquer box, displayed in the exhibition, shows the shades of yellow, blue and purple that perfectly match the tones he used in an 1887 fruit still life.

The artist’s association with yellow in particular goes back to his famous “Sunflower” series, created in 1888 and 1889 — but Blokland said that he didn’t necessarily use the color more than others over the course of his career.

His early paintings, made in his native Netherlands and Belgium, depicted the harsh reality of rural life using a dark, earthy palette. It wasn’t until he moved to Paris in 1886 and was influenced by French painters like Signac, Paul Gauguin and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, that he began to experiment with a warmer, livelier pigments.

When he moved to Arles, his love of yellow came into full bloom — as did his style. There, he depicted the sun-drenched landscape, painted his new home in “The Yellow House” (1888) and made self-portraits wearing a corn-yellow straw hat.

“It was a color that challenged him to push this expression and emotion in his painting even further,” Blokland said, “because it was such a strong color, and it was all around him in Arles.”

This “yellow period” lasted through van Gogh’s time at a mental hospital in nearby St. Remy. By the time he moved to Auvers-sur-Oise, just outside of Paris, his paintings had bacame somewhat darker again, using more purples and blues.

One of Blokland’s revelations when putting together the show was discovering that yellow books often appeared in paintings of van Gogh’s era. These would have been instantly recognizable to his contemporaries as French paperbacks with sexually suggestive or otherwise racy content, giving a new meaning to van Gogh 1887 still life “Piles of French Novels.”

In part because of those books, “yellow became synonymous with all things modern and fashionable, and risqué,” Blokland said. A British magazine from the time called The Yellow Book, displayed in the exhibition, published edgy or scandalous articles, often written by female writers, which was rare in the late 1800s.

The century’s final decade was sometimes referred to as the “Yellow Nineties,” a decadent, avant-garde period that van Gogh would not live to see through. He killed himself at its cusp, in July 1890.

At his funeral, his friends and family brought yellow flowers, and his coffin was covered with sunflowers and yellow dahlias: “yellow flowers everywhere,” as his painter friend Bernard noted in a letter. “It was, you will remember, his favorite color,” he added, “the symbol of the light that he sought in people’s hearts, as well as in works of art.”

Yellow: Beyond Van Gogh’s Color Through May 17 at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam; vangoghmuseum.nl.

The post Van Gogh and the Meaning of Yellow appeared first on New York Times.