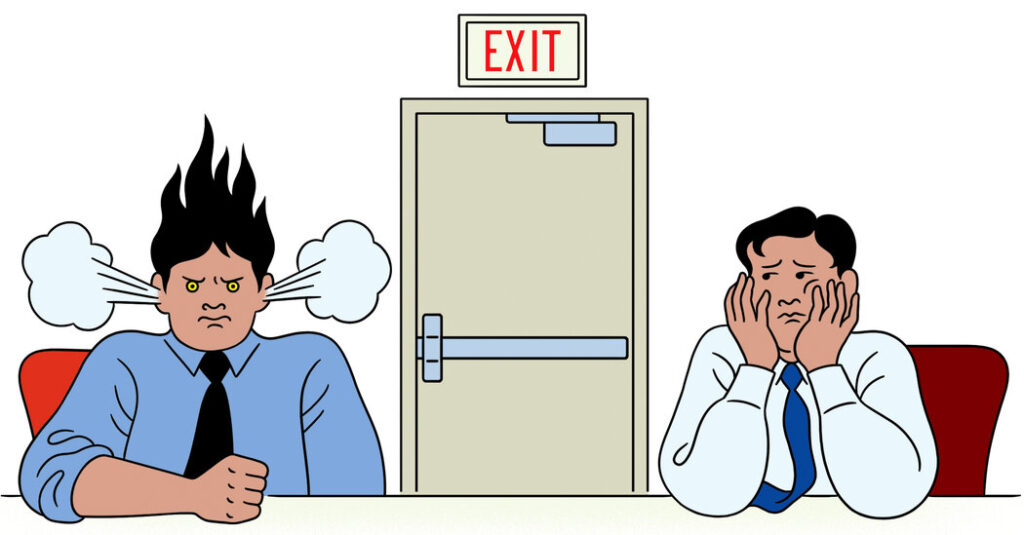

I joined my family’s company, and it has been messy. The main shareholders are my mother and her two sisters. From my generation, there’s a cousin who also works here. He’s complicated, with a history of anger issues and past verbal aggression toward employees and family. He no longer raises his voice, but the negativity remains. When he’s upset, everyone can feel it through his behavior, which includes slamming doors or withdrawing completely. After more than two years of working with him, I’ve realized I don’t want to have him as a business partner.

Right now, disagreements end with my mother, the chief executive, making the final decision. What worries me is what will happen once she steps down. My mother has said that she sees me as the person best suited to lead the company, and she’s convinced that my cousin should not. She also reminds me that she has invested a great deal of time, money and effort in preparing me for this role.

I like the company and have learned so much from being here. The work is challenging and fulfilling. But I can’t picture spending the rest of my career working with my cousin. I’m also concerned about what might happen — both to the company’s future and to my mother’s legacy — if I decide to step away after the succession.

I have the skills to succeed elsewhere, and I’m not afraid of doing so. But leaving would delay my mother’s plans to retire, which adds more pressure. What are my obligations in this situation? — Name Withheld

From the Ethicist:

When someone habitually communicates anger through intimidation, withdrawal or physical displays, I’d say it qualifies as a workplace problem. Make sure your mother, the chief executive, is fully informed about what this man does, how often and its effects on the team (including you). If your mother has settled on you as her successor, then she and the other shareholders should establish clear expectations for your cousin’s role, including behavioral requirements. That can include coaching or counseling, if he is willing, and a plan for what happens if the behavior continues.

You might hold back from mentioning that you’re considering leaving so that the focus is on governance and accountability. Still, at some point, she may need to know that while you care about her legacy and the future of the company, your willingness to take on a long-term leadership role depends on a workplace where you can rely on colleagues to act professionally.

Because your cousin is presumably the child of one of her sisters, all this will require difficult family conversations. But your mother cares about her legacy too and should be ready to do what the situation calls for. It sounds as if you don’t think you’d be able to fire or discipline this cousin even if you were the chief executive, given the shareholder arrangement. That’s why this problem needs to be confronted while your mother still has the standing to secure the other owners’ backing. She has invested a lot in preparing you for leadership, and this has weight. It doesn’t give her a majority stake in the rest of your career.

Readers Respond

The previous question was from a reader who was torn about whether to do I.V.F. with genetic testing for her second child. She wrote:

Shortly after my son was born, he was diagnosed with cystic-fibrosis-related metabolic syndrome, a condition that sometimes becomes a full cystic-fibrosis diagnosis. Children born with my son’s gene combination (one C.F.-causing gene and one with varying clinical consequences) have a chance — low, but not so low as to be disregarded — of transitioning to C.F. by age 8. … Many others are thought to be healthy throughout their lives, though there’s little data on the outcomes. My son, who’s almost 3, is asymptomatic and thriving. … But for future pregnancies, we are debating whether we should do I.V.F. with genetic testing of the embryos before implantation. … With such a small risk of illness, does this type of embryo selection border on eugenics, especially now that a new class of drugs has transformed life for many with classic C.F.? — Name Withheld

In his response, the Ethicist noted:

There are important ethical questions about choosing not to implant an embryo because the resulting child would have a risk of growing up to have a serious illness. Among bioethicists, the “expressivist” argument captures the worry that when we prevent people with a condition from being born, we’re expressing disfavor toward actual people with that condition. But you already have a child with this condition, whom you couldn’t love more. … In choosing to implant an embryo without the C.F.-associated gene variants, you’d surely be expressing a judgment about states of health, not a judgment about the worth of existing people. The word “eugenics” trails a dark history of coercive sterilization, racism, ableism and more. But, in general, sound arguments aren’t tethered to a specific word. You should be able to rephrase the concern using other words. … If the conclusion doesn’t feel so compelling without “eugenics,” then the word may be doing too much of the thinking for you.

(Reread the full question and answer here.)

⬥

When our son was 3, we learned he had a genetic disorder that comes along with severe, difficult-to-treat epilepsy. For our next child, we hope to use I.V.F. with genetic testing. Ultimately I made my decision based on how I would explain it all to my son in the future. It’s my firm belief that he would not choose to allow his younger sibling to potentially suffer and would rather have a healthy sibling, so we can all be as fully present for one another as possible. In the end, this is a decision that will be made with love, not hate. — Ashleigh

⬥

I think that it would be the height of selfishness not to be careful about having another child when you know that your genetics offer a chance of that child suffering from a horrible disease. If you aren’t bothered by the ethical questions around selecting an embryo that doesn’t carry those genes — which is really the question of discarding embryos that do — then by all means, go for it. Alternatively, you could choose to adopt an existing, frozen embryo that has already been tested, or you could get an egg donor who has been vetted for genetic issues. There are a lot of solutions that don’t involve rolling the dice with a child’s life. — Dana

⬥

I’m in the fourth generation of a family afflicted by Lynch syndrome. For our family, it means aggressive cancers beginning around age 30. Surveillance prolongs life but does not reduce the suffering. I’m 68 and look like I was in a pirate fight, with most of my small and large intestines removed and half a kidney gone. I lost one sister at 34; another sister has Stage 4 cancer at 52. Now, the sixth generation of our family is doing I.V.F. to select Lynch out of our genes. This is a lifelong challenge and I welcome any solution to prevent the spread. — Linda

⬥

As a doctor who has been doing I.V.F. for over 40 years, I have had some time to think about these things as new applications, such as genetic testing, have appeared. You are asking if you should do something that could significantly improve the life of a future child. If there were some way other than I.V.F., would you not do that? If you have moral or ethical objections to I.V.F., then don’t do it. Otherwise, see this as an opportunity to have a healthier child who won’t be in the same dilemma as you are when he or she wants their own children. — Donald

The post Do I Have to Take Over the Family Company if I Can’t Stand My Cousin? appeared first on New York Times.