A flurry of new studies is shedding light on one of the biggest steps in the history of life: the evolution two billion years ago of complex cells from simpler ones. In the oceans and on land, scientists are discovering rare, transitional microbes that bridge the gap.

The differences between complex cells, including those in the human body, and simple microbes such as E. coli are stark. Complex cells are packed with compartments; one, known as the nucleus, stores DNA; others, called mitochondria, contain enzymes that generate the cell’s fuel supply. Complex cells are also supported internally by a mesh of filaments, that they use to crawl by breaking down parts of it and building new extensions.

E. coli has none of that: no skeleton, no mitochondria, no nucleus.

These differences, and many others, form one of the deepest divisions in the natural world. Species composed of complex cells are eukaryotes, a group that include animals, plants and fungi, along with protozoans. Simple microbes like E. coli are known as prokaryotes.

Prokaryotes arose more than four billion years ago. Eukaryotes emerged much later, somewhere between 2.5 and two billion years ago. How complex eukaryotes evolved from simpler prokaryotes has left scientists scratching their heads for decades.

In the 1990s, one important clue came from close studies of mitochondria, the fuel factories of the eukaryote cell. Researchers discovered a tiny set of genes inside mitochondria that was not at all like the DNA in the nucleus. Instead, mitochondria have a strong genetic link to bacteria that use oxygen to produce fuel.

That discovery suggested that the ancestors of eukaryotes swallowed oxygen-fueled bacteria and then used them to generate their own fuel. But that insight still left many questions about eukaryotes unanswered. For instance, what sort of organism was the original cell that engulfed mitochondria?

A major clue came in 2015. Scientists extracted fragments of DNA from sediment scooped up from the floor of the Arctic Ocean, and then pieced them together into entire genomes of sediment-dwelling microbes. One turned out to be unlike anything found before: a prokaryote with numerous genes previously found only in eukaryotes.

Among those eukaryote genes were some that were involved in building cellular skeletons. Others help build compartments in which eukaryote cells break down old proteins.

Scientists began looking for other members of this eukaryote-like lineage. The search at first was achingly slow, and most of the discoveries came to light in deep-sea sediments. Scientists named the lineage Asgard, after the home of the gods in Norse mythology.

Brett Baker, a microbial ecologist at the University of Texas at Austin, has spent the last few years speeding up the search. He and his colleagues have gone on Asgard-hunting expeditions to deep-sea sites off the coast of California and in shallow coastal waters in China. Back at their lab, the researchers used powerful new techniques to find DNA from rare microbes.

The search has paid off, as the scientists reported on Wednesday. They found 404 new species of Asgard on their expeditions. They also discovered that databases from previous surveys contained 30 more Asgard genomes that had gone overlooked. All told, in a single study, the scientists have nearly doubled the total diversity of known Asgards.

“We’ve exploded the diversity of Asgards, and there’s no end in sight,” said John Archibald, an evolutionary biologist at Dalhousie University in Canada who was not involved in the new study.

Many of the new Asgard microbes live in the deep sea, but others dwell in coastal waters. But others are land, in habitats ranging from permafrost tundras to lagoons. They may be rare, but they’re also widespread.

“If you can go in your backyard and sequence soil, you’ll get Asgard,” Dr. Baker said.

Even as scientists have improved at finding Asgard DNA, they are still struggling to study live Asgard cells. Christa Schleper, a microbiologist at the University of Vienna, and her colleagues spent eight years figuring out how to grow Asgards that they had found in oxygen-free sediment on the coast of Slovenia.

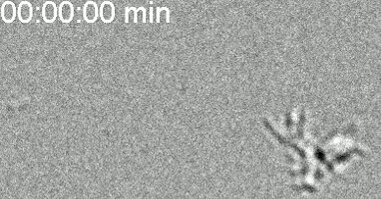

At last, the researchers put some live Asgards on glass slides and trained a video camera on them. When they sped up the footage, they saw the microbes crawling across the slide — the first time anyone had seen them in motion.

“There was a lot of shouting and jumping,” recalled Philipp Radler, a postdoctoral researcher in Dr. Schleper’s lab.

The movement of the Asgards offers some tantalizing clues to the origin of eukaryotes. They crawl by reshaping their cellular skeleton, building long tentacles that they use to reach out and grip the slide. Other prokaryotes don’t move this way — but eukaryotes do. The videos suggest that Asgards evolved some of the key hallmarks of eukaryotes, such as a skeleton they could use to crawl, long before eukaryotes existed.

Other scientists have also been investigating another crucial step in the origin of eukaryotes: how they gained mitochondria.

The ancestors of bacteria must have been microbes that breathed oxygen, and so must have lived where oxygen was abundant. Asgards that lived in oxygen-free sediments would not have encountered them. But Dr. Baker’s new study offers some clues into how this monumental meet-up may have happened.

Dr. Baker and his colleagues have found many new Asgards thriving in coastal waters with high levels of oxygen. A close look at their genes revealed hints that they use the oxygen for their metabolism.

“They appear to breathe oxygen and eat organic carbon — which is very familiar to us because we’re doing that right now,” Dr. Baker said.

Dr. Archibald said that scientists had come up with a lot of different scenarios for how eukaryotes evolved, but that it was hard to evaluate them without solid data. The Asgards that Dr. Baker and other researchers are finding now bring the origin of eukaryotes into sharper focus.

“We’re really breaking down impasses with real organisms,” Dr. Archibald said.

Dr. Baker and his colleagues now argue that the first steps on the path to eukaryotes took place on early Earth, when it lacked oxygen. Early Asgard microbes evolved a cellular skeleton, using it to creep around the ocean floor.

Earth’s atmosphere started to change around 2.5 billion years ago. Certain bacteria evolved photosynthesis, enabling them to absorb carbon dioxide and sunlight to grow. They cast off oxygen as waste. That oxygen gradually built up in the atmosphere, and then penetrated shallow coastal waters.

For many microbes, the new oxygen was toxic. But some Asgard microbes that lived in coastal waters adapted to withstand oxygen, and then to thrive on it. “And then they passed that on to eukaryotes,” Dr. Baker speculated.

Dr. Baker also suspects that Asgard microbes encountered bacteria that would become mitochondria in oxygen-rich coastal waters. He points to his team’s survey of the sea off the coast of China, where they found bacteria closely related to mitochondria living in the same sediments as Asgard microbes.

Once Asgards gained mitochondria, they dramatically ramped up their oxygen-based metabolism. These new eukaryotes gained an abundant energy supply that allowed them to grow larger with more capabilities, like preying on prokaryotes. The world would never be the same.

Kathryn Appler, a microbial ecologist at the Pasteur Institute who worked on the new study with Dr. Baker, said that scientists do not have to travel back two billion years to test this hypothesis. Instead, they can search coastal waters today. It’s possible that living Asgards are following the same path that the first eukaryotes took, forming intimate partnerships with bacteria.

“It keeps me up at night sometimes, wondering what is happening in the sediments today,” Dr. Appler said.

Carl Zimmer covers news about science for The Times and writes the Origins column.

The post How Microbes Got Their Crawl appeared first on New York Times.