Joachim Trier’s “Sentimental Value” is nominated for an impressive nine Academy Awards, among them the first best picture nod for a Norwegian film and the auteur himself for both directing and co-writing (with longtime collaborator Eskil Vogt) the family drama’s original screenplay.

But perhaps the film’s most remarkable achievement, Oscar-wise, is four first-time acting nominations.

Renate Reinsve, the director’s muse from his acclaimed feature “The Worst Person in the World,” is a lead actress nominee for playing popular but troubled Oslo stage and TV actor Nora Borg.

Sweden’s Stellan Skarsgård — whose career has run the gamut from Lars von Trier’s arty provocations to Marvel, “Dune,” “Star Wars” and “Mamma Mia!” franchise entries — is, at 74, arguably leading the supporting actor race. He plays Nora’s long-absent father Gustav, a once-respected writer-director trying to revive his career with a semiautobiographical project he needs his daughter to star in — and she wants nothing to do with.

Norwegian Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas and American Elle Fanning both have supporting actress nods for, respectively, Nora’s younger, more conciliatory sister Agnes and the Hollywood star Rachel Kemp, who yearns for artistic cred and could definitely be the replacement casting that gets Gustav’s movie financed — if she can handle its very Scandinavian main role.

But while suicide, wartime atrocities and intimate betrayals haunt the picturesque Borg family home, Trier does not take “Sentimental Value” into obvious Bergman territory. The four principals’ unmet personal and professional needs play out in unpredictable, funny and warm — as well as shattering — ways.

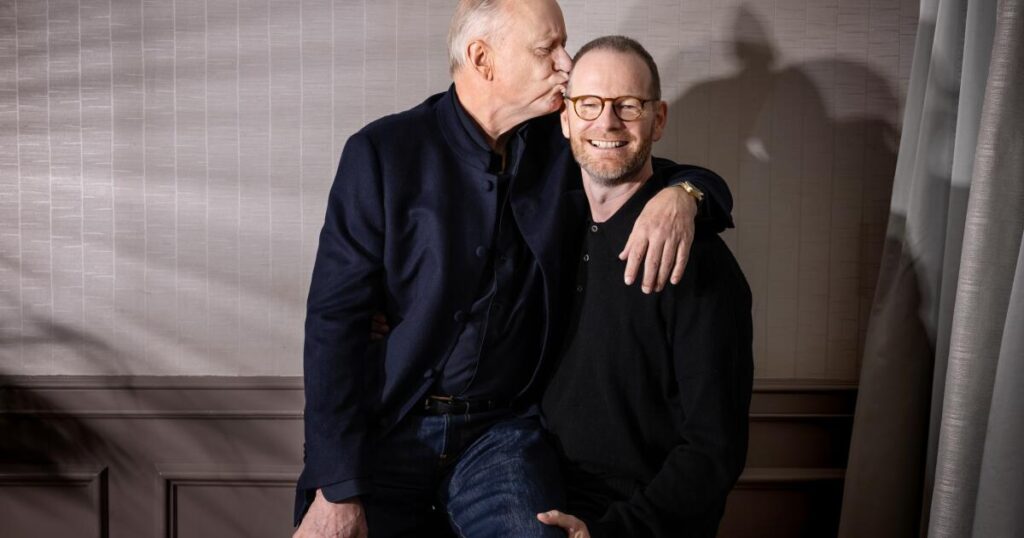

Though both dressed in black when they spoke with The Envelope at the Four Seasons Los Angeles recently, Trier and Skarsgård exhibited high spirits and fond camaraderie while examining the mysteries of relationships and art.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

You guys really seem to enjoy all the awards–season hoopla.

Trier: We’ve become such good friends, it’s like we really love each other. We made this film about a terribly dysfunctional family, but we are actually quite functional!

The whole gang looked so excited watching the nomination announcements on that viral video.

Skarsgård: I was most happy that Elle and Inga got nominations. I’ve lived my whole life without a nomination — not a problem! — and you know that Renate will get a couple of Oscars, probably, in the near future. So it was beautiful.

For me, it’s the highest award in the world for a film actor. I do appreciate it, but it doesn’t mean much professionally.

Especially for you, who’s done just about everything a film actor can. Gustav seems like a special role, though.

Skarsgård: It is one of the best roles I’ve gotten in my life, but not on paper. It’s with Joachim directing it. He is interested in whatever nonverbal reaction you have between the lines. That is the acting I like, that kind of attention to the details of the psychological narrative that is not the normal film narrative.

Did you gain new insights into the plight of aging film workers?

Skarsgård: [grinning] Well, I’m in the beginning of my career still.

Tell Stellan why you wrote Gustav for him, Joachim.

Trier: You’ve worked with Spielberg and Fincher and all of these great directors. I wanted to offer you a proper drama role where you can also be very vulnerable and honest about who you are. It’s not your biographical story at all — you have very good relationships to your kids and this man doesn’t — but you really brought your heart to it and made him somehow a human being in the three-dimensional sense. And I think your colleagues recognized that.

Since a stroke damaged his short-term memory, Stellan receives prompts through an earpiece on set. How was it to work with that?

Trier: I witnessed a process that moved me deeply, and I think it’s made this film better. First, we decided to make Stellan’s prompter [Vibeke Brathagen, a prompter at Oslo’s National Theatre, where a number of “Value’s” scenes were filmed] part of the ensemble. To see an artist of this caliber in such a vulnerable position of trying something new coincided with portraying a character at a turning point in his life. Both the character and Stellan are working this deep feeling of, can I go on? Will there be another chance for me?

Skarsgård: It’s permanent, I can’t remember lines. What worried me was not only the language, but I had problems with the thought that goes over several beats. So I have to talk shorter and more in pulses. And it’s hard work because it’s not just somebody prompting and you repeat it, but rhythm between the actors is very important. To keep that rhythm, the prompter has to talk over the other actor’s lines. So you’re hearing two lines at the same time but you only react to one.

How was working with Renate?

Trier: She’s like a force of nature. We don’t know how she does what she does. We did one day of rehearsals and Stellan came up and gave me a hug [and] said, “Who is this person? She’s incredible!”

Skarsgård: I remember that! Her face is transparent; you can see every feeling. She’s natural and curious and has a musicality that’s wonderful. I’m talking about rhythm again, of our scenes together. It was really good fun.

Inga?

Trier: One of the biggest challenges of this film was finding someone to play Renate’s younger sister who could match her level of performance, looked like her and spoke Norwegian fluently. There’s not an endless pool of those, but we did see around 200 people. When Inga arrived, it was very clear. There is an authenticity, a groundedness and something unneurotic and unproblematic about her approach. The earnestness transferred into the character and lifted it. She’s escaped the mad circus of the Borg family in a way — said, “I want my own family.”

And Elle?

Trier: I really wanted to work with Elle for her skills and craft, but she’s also grown up in the Hollywood system. She could portray this person yearning to connect with something deeper as an actor.

She offered a lot of nuanced, different takes. There’s a scene where Rachel’s reading a text and crying in front of Gustav. It’s good acting, but there’s some sense that she’s acting stylistically, different than how he wants. Elle did several versions of that so we could find the right tone. She’s like a super-sophisticated jazz musician.

Saying the house is like a character too sounds a bit lame. But you really did some amazing things with the place, up to and including copying its interiors on a soundstage — which, despite his desire to shoot in his ancestral home, is ultimately where Gustav makes his film within the film.

Trier: I’ve been very aware that this film is about generational trauma and the house witnessing the 20th century. It’s subtly there. I’m not making a huge point of it. But for me that mattered when making the film. The thing is, how do these things percolate three, four generations later? I’ve felt that, and I know a lot of people have, and those conversations matter.

I wouldn’t use the word “device,” but the house gives us a more poetic approach to how quick time moves. The house has witnessed what the family can’t speak about. What Gustav’s mother went through. What he has felt but doesn’t know how to articulate. How it’s affected him toward his daughters. How they are choosing or not choosing to have a family. It’s connected through the gaze of the house.

So how to make that interesting and cinematic? I had a wonderful production design department, and our cinematographer, Kasper Tuxen, built a replica of the house on a soundstage. We went between that and the real house, and we did every 10 years of the 20th century with different lenses, different film stocks, different production design. It’s a love letter to cinema, also. It gave us an opportunity to nerd out and say, “We’re in the ’20s and ’30s, now we’re in the ’60s” and really play with the form.

Though he’s a master manipulator, Gustav always has to compromise to get a semblance of what he wants. Guess that’s directing in a nutshell, huh?

Trier: That’s the drama. How far do you have to be pragmatic without losing your art and still sustaining your career? All people in this business have to make tough choices at times. I could project my nightmares through him. What if I had been that person who didn’t spend time with my family? What if I had to compromise?

Skarsgård: There’s a lot of things out of Gustav’s control. He can’t manipulate his family enough; he’s trying, he brings out all the tools — be funny, be nice, everything — but he doesn’t reach them, and it’s tragic. When you see him directing, you see that he has the sensibility and psychological intelligence of a good director. It’s very common that those directors are not very good with their family life.

Speaking of compromises, the specter of Netflix hangs over Gustav’s whole project.

Trier: Someone asked me if this is a critique. No, it’s an encouragement [chuckles]. I mean, wouldn’t it be wonderful if a lot of the great films Netflix does were shown in theaters first?

You concluded your Golden Globes acceptance speech, Stellan, saying “Cinema should be seen in cinemas.”

Skarsgård: One of the great things with cinema is it can touch on all the things that are inexplicable, that you cannot say in words. The narrative form of television is based on you not watching. It explains everything through dialogue so you can make pancakes at the same time. But cinema is the only place where you can do those silent things.

“Sentimental Value” says so much with wordless glances and still faces.

Trier: Now we’re speaking about Stellan’s character. That silent space, where words don’t work for that character and the trauma which can never be quite articulated, is also connected to the silent space where we hope that art can be created. It’s a bit of a yin and yang, but there’s something about the traumatic and the sublime that’s connected in the world. I see it all the time. I’ve spent my whole life hanging out with creative, wonderful people, and in ways that they can’t explain, you feel that you’re working through something. It might never be resolved, but you’re using what you can, you’re telling what you can.

To end on the wonderful Joan Didion quote — a writer we all adore, of course — “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” It’s a mystery to me, but the film is certainly trying to deal with that somehow.

The post ‘Sentimental Value’ isn’t a critique of Netflix. ‘It’s an encouragement’ appeared first on Los Angeles Times.