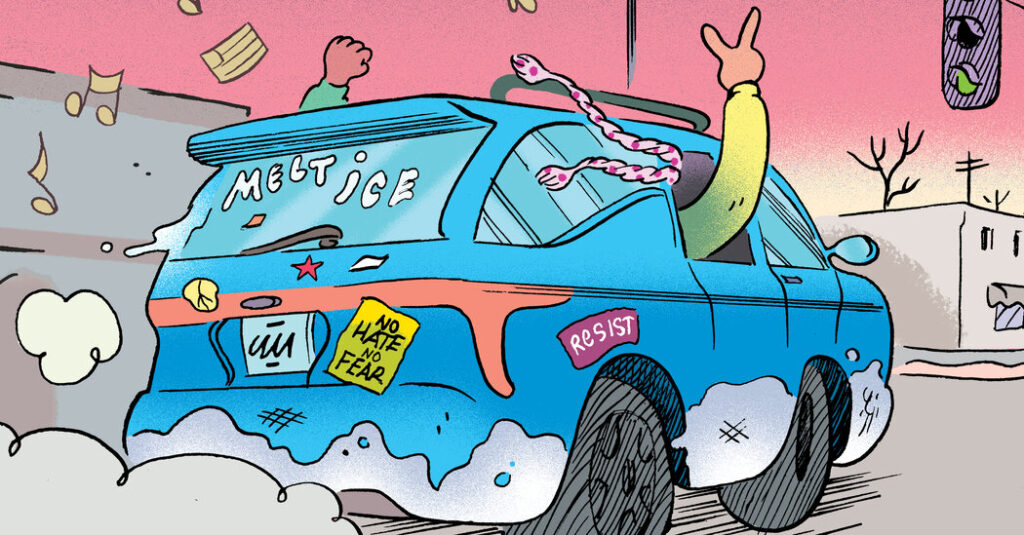

In the resistance we drive minivans, we take ’em low and slow down Nicollet Avenue, our trunks stuffed with hockey skates and scuffed Frisbees and cardboard Costco flats. We drive Odysseys and Siennas, we drive Voyagers and Pacificas, we like it when the back end goes ka-thunk over speed bumps, shaking loose the Goldfish dust. One of our kids wrote “wash me” on the van’s exterior, etched it into the gray scurf of frozen Minneapolis slush. Our floor mats smell like mildew from the snowmelt.

In the resistance we play Idles loud, we prefer British punk, turn the volume up, “Danny Nedelko,” please and thank you — we cast that song like a protective spell across our minivans: Let us be bulletproof, let us be invisible. We double-check the address, two new kids in the car pool today, three more families requesting rides in the Signal chat. We scan our phones to see which intersections to avoid: armed ICE action in Powderhorn; saw a protester get pushed down. This is in the weeks following the killing of Alex Pretti by federal agents. Following the killing of Renee Good by a federal agent.

In the resistance we drive the high school car pool, that holy responsibility, the ferrying of innocents among the wolves. We drive kids we’ve never met before from families afraid to leave their houses, and most mornings we’re in our pajamas, a staling doughnut grabbed with yesterday’s cold coffee, teeth unbrushed — and OK, fine, that might just be me. You wouldn’t be the first to cock an eyebrow at my personal hygiene.

And OK, fine, I don’t even drive a minivan, if you’re going to be pedantic — it’s a dark Chevy Traverse that looks just like an ICE truck. So in those subzero mornings, when I pull up in front of a new address, I roll the window down and shine my smiley pink face into the day — I know how this looks, sorry, sorry! — and I wave wave wave my cartoon wave right up to the point where those eyes peering from behind bent mini blinds register the thought: No… no, I do not think that man could be ICE.

We’ve been doing this since December, eight weeks-going-on-nine-going-on who knows. Kids stopped going to school when thousands of ICE officers arrived in Minnesota. They didn’t want to take the buses anymore, their parents too nervous to release their children onto the block, lest they get swept up by masked agents in flak jackets. This was before the 5-year-old in the blue bunny hat got taken, before a fourth grader in Columbia Heights disappeared, before my middle child’s middle school went into lockdown because ICE trucks were prowling outside her algebra classroom. A network of neighborhood moms and dads bloomed organically, divvying rides, vetting newcomers. There were no open calls, just friends talking with other friends, seeing who might want to help.

Today I’m driving a boy with big bright eyes and floppy hair and golden retriever vibes. He’s got his guitar case this afternoon, performed something for the class, and when I ask about it he smiles and nods and looks down at his seat. (I won’t name any of the kids I drive out of fear of government reprisal.)

Today I’m driving a girl with red lipstick and a gentle, cautious smile. Today I’m driving those sweet, shy sisters who politely take doughnuts from my proffered box even though they never eat them in the car. Today I’m driving the dignified and serious girl who told me English is her favorite class. They’re reading “Romeo and Juliet,” they’re writing sonnets. She told me next year she wants to take A.P. English. Today she’s going downtown to the protest, going because her parents can’t leave the house. Her father came out to shake my hand the first day I picked her up. Most mornings her mother waves from behind a cracked door. They’ve postponed her quinceañera for now; Mom says it’s going to be a Sweet Sixteen next year.

Today I’m driving a boy with braces and unstylish glasses, a dazed and daffy air. He’s always smiling about something. He is last on my drop-off list, four different stops today, and he was squeezed into the far back next to a girl in his grade. Am I wrong to think that neither was leaning away from the other, may in fact have been scrunching in a little closer? A gentleman never tells. Just before we reach his house I ask how his day went and he jolt-snorts awake, laughing. Oh, man, I was up so late last night, playing video games with my friends, he says. He’s bashful now. My friends are too funny. I pull up to his place and we scan the area for suspicious vehicles. I watch him turn the doorknob, step inside.

What they don’t often tell you is how beautiful the resistance can be. In the evening, on the day that Alex Pretti, an I.C.U. nurse, was shot to death by federal agents in front of Glam Doll Donuts, my wife and I drove through Minneapolis. There were candlelight vigils on nearly every corner we passed, some corners with four or five people cupping tiny flames, some corners with 50 neighbors milling about, communing, singing, stoking a firepit hauled to the sidewalk, lighting up the little Weber grill, just hanging out in the frozen dark.

What they don’t often tell you is how fun the resistance can be: the marches joyous and laced with adrenalized anger, people cheering the brass band that thumps its way down the block, chanting and pumping fists, belting out a ubiquitous profane call and response about ICE.

The biggest march was planned for a day of general strike, Jan. 23, when the weather was projected to be -9 degrees, wind chills reaching the negative 20s. People began to fret, worrying about low turnout, but when my wife and I arrived in downtown Minneapolis with our children we encountered one of the largest assemblies of humans I’d seen in person. Some news outlets reported 50,000 people.

I was not surprised, had not forgotten that people in the North have been practicing for this their entire lives. Mention a negative temperature and the Minnesotan eye is liable to glaze over in reverie — it is a near-erotic sensation, the act of considering which fleece to pair with which shell, which anorak has the thickest fur-lined hood, whether it’s time to bring down the warmest warm coat from the attic, whether the heated vest is still charged.

As we tramped through the arctic streets, a bearded dude pulled a wagon bearing a generator and a vat of bubbling soup, dishing up bowls for anyone who cared to slurp. My 13-year-old daughter carried a sign that said, “You can’t shoot us all,” but most of the signs were funny and usually vulgar, along with numerous variations on crushed and salted ice. A young woman held a piece of cardboard with a message insulting ICE agents’ mommas; I did a double take a few minutes later when I saw a different person holding aloft a sign with the exact same phrasing, the sentiment universal, apparently.

After the marches are over, after we’re warm at our fireplaces, we laugh at videos of ICE agents performing unintentional vaudeville pratfalls on the slicked-out sidewalks, feet swooped from underneath. We share the clips of the white supremacist agitator who, aiming to profit from the city’s chaos, organized a march that was meant to culminate with a burning of the Quran in a Somali neighborhood — only to be abandoned by his scraggly followers and met by a crowd of jeering Minnesotans who pelted him with water balloons in the subfreezing afternoon. And there was satisfaction, of course, in seeing that cosplay commandant get yanked from the spotlight he appeared to so desperately crave and retired back to the desert, while understanding that his removal was symbolic, an action that changed nothing. Still, in these unsettled times, one must nurture joy wherever one can.

As the poet Toi Derricotte writes, “Joy is an act of resistance.”

Everyone is doing his part here, each to his ability. This is easier to accomplish, it seems, when joy and love are the engines. Outside the Bishop Henry Whipple Federal Building, where detainees, some of them American citizens and legal residents, are being held without beds or real blankets, the grannies of the Twin Cities are serving hot chocolate to college kids in active confrontation with ICE. I know of an off-grid network of doctors offering care to immigrants, a sub rosa collective of restaurateurs organizing miniature food banks in their basements. A friend of mine is a pastor who went with around 100 local clergy members to the airport in protest. Another friend is an immigration lawyer who spends his days endlessly filing habeas petitions, has gotten 30 people released from detention over the last few weeks. He recently offered a training session on how to file habeas petitions and 300 lawyers showed up, eager to do the work pro bono.

Every day and night, in the neighborhoods most affected by ICE raids, volunteers stand on street corners and patrol the blocks, phones and whistles ready. The middle-aged ladies of the metro area still take their jaunty 5 p.m. walks, but wearing neon observer vests now. My wife told me about a plumber out in the burbs offering his services free to immigrants affected by the federal occupation — and truly, when the suburban plumbers are against you, you can be sure you’re on the wrong side of history.

Our loose parent network keeps growing, more than 80 of us now. The demand is greater each week, as people in hiding talk with other people in hiding. The first week we had five families riding the car pool; by the seventh, more than 60 families had requested rides, just in our small corner of Minneapolis. We’ve started driving kids’ parents to their jobs, started putting up rent for people who can’t leave their apartments. This is happening in neighborhoods and suburbs across the Twin Cities. We are legion, the local moms and dads, we cruise the city in our minivans. You can’t shoot us all.

Here’s what you need to remember: There is no reward that comes later. No righteous justice will be dispensed, not soon and not ever. Renee Good and Alex Pretti don’t come back to life. The lives of their loved ones are not made whole again. Thousands of people will remain disappeared, relatives scattered, families broken. This story does not have a happy ending, and I can assure you the villains do not get punished in the end. If that is your motivation, try again, start over.

But you also need to understand — and this is equally important — that we’ve already won. The reward is right now, this minute, this moment. The reward is watching your city — whether it’s Chicago or Los Angeles or Charlotte or the cities still to come — organize in hyperlocal networks of compassion, in acephalous fashion, not because someone told you to, but because tens of thousands of people across a metro region simultaneously and instinctively felt the urge to help their neighbors get by.

So in the resistance you drive the car pool. It’s fun, and it’s mostly not scary. Your invisible shield of whiteness has developed a small fissure. You understand that being a white mom dropping a kid at elementary school may no longer save you from being killed in the middle of the street, that being a bearded white bro may not stop government employees from firing their Glocks into your back outside the Cheapo Records. When these thoughts intrude, you slow down to the speed limit, you turn Idles a little louder, you play “Danny Nedelko” again. That song comes from an album called “Joy as an Act of Resistance.”

Today I’m driving a girl who never speaks other than to say thank you. She’s out of the car now and trying to clamber ungracefully over a dirty ice bank that walls off the roadway from her house. There is no entry point — she’d have to walk down to the corner to gain access — and I’m cursing myself for where I’ve dropped her off. The skies are an unsympathetic oatmeal. It is very cold, the dark dead of winter.

Out on the stoop of her building, the girl’s mom and little sister are waiting. The mother looks on nervously, wishing to minimize this vulnerable transition point between car and home. The little sister is probably 3 years old. She is in pigtails and wearing footie pajamas and she is radiant, leaping up and down, clapping, ecstatic to see her big sister come home. The quiet girl is stone-faced and stumbling, and eventually she makes it across the wall of gray ice to her stoop, where her little sister grabs her by the leg.

I’ll admit: This was the only time I cried, throughout this whole disgusting affair, as I sat in my car watching the girl in the footie pajamas clapping for big sister’s safe return. For a half-second I had the instinct to punch the steering wheel as hard as I could. But I’m not quite so melodramatic, and I was worried I’d just beep the horn awkwardly and look like a fool.

This afternoon I’m driving a brother and sister. We’ve been listening to the radio, which reports that almost all of the 3,000 ICE agents involved in the surge are leaving our state. No one believes it, not really, this declaration from the agency that asked us again and again to disbelieve our eyes, to accept that nurses were domestic terrorists, that children were violent criminals. In the meantime, the official story behind a third shooting by federal agents in Minneapolis has been outed as a lie, the offending agents now suspended for providing “untruthful statements” under oath. So you’ll have to forgive our collective skepticism. The drawdown has been rumored for a while now, but the car pool is still booked, with new families requesting assistance each week. Our network won’t be shutting down any time soon.

But there is a strange giddy energy in the car today. It’s the start of a long holiday weekend and the siblings are buzzing. The first time I met them, as they walked through the parking lot of their apartment building, I watched the sister draw a heart in the frost on the windshield of her mother’s car. When I ask about plans for the holiday, the sister says, I’m going to sleep all weekend. She starts laughing. I’m going to relax! It’s been so cold for so long, hovering around -8, -10, -15 since the start of the new year. But today the sun is out and the sky is brilliant blue. The days are getting longer. Thaw is coming.

Will McGrath is the author of the books “Farewell Transmission: Notes From Hidden Spaces” and “Everything Lost Is Found Again.”

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.

The post In the Resistance, We Drive Minivans appeared first on New York Times.