The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had been leading a crusade to end legal segregation and expand voting rights in the South for more than a decade. But by 1966, he had grown troubled by what he saw in the North, where poverty remained entrenched in segregated urban ghettos.

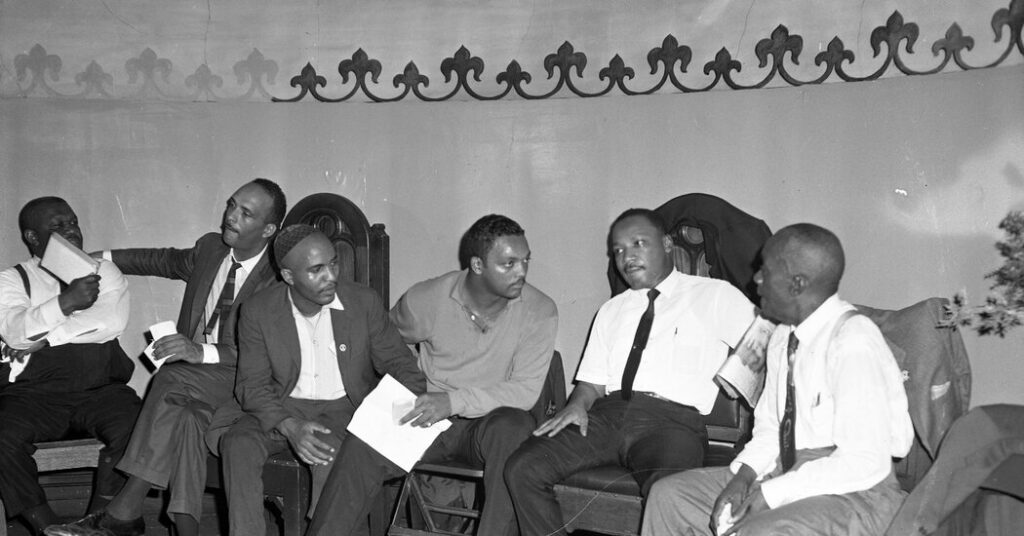

To expand what he saw as a broader, national fight for economic equality, Dr. King knew the person he wanted to spearhead the effort in Chicago — a 24-year-old seminary student named Jesse Jackson.

In interviews conducted before Mr. Jackson’s death on Tuesday, those who knew him then or worked with him later recalled a man burning with ambition, charisma and ego.

Recognizing Mr. Jackson’s talents, Dr. King appointed him as the coordinator of his new program, Operation Breadbasket. At the time, Mr. Jackson was the youngest member of Dr. King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

The program, which started in Atlanta, leveraged direct confrontation and sometimes boycotts to urge corporate America to implement equal opportunity hiring practices for minorities. It would become a model for urban activism, expanding on Dr. King’s lessons from the Montgomery bus boycott. It was also the training ground for the urban racial politics that Mr. Jackson, a southerner, would excel in.

“He learned where the strengths are in people, he learned where the soft points are, where you can move someone by the heart but you can also move them with economic arguments,” said the Rev. Martin Deppe, a founding member of Operation Breadbasket.

The first time Mr. Deppe, 90, listened to Mr. Jackson, he said he was taken aback by the self-assurance of a young seminary student who could stand before 300 hundred ministers and command their respect, even if his oratory and demeanor at times overwhelmed them. Originally brought in to coordinate Breadbasket for the S.C.L.C., he was running the meetings by the end of the first month.

“He had an idea a minute,” Mr. Deppe said. “We couldn’t even implement all his ideas.”

Chicago in 1966 would prove to be a fierce battleground for the civil rights movement, where its southern leaders were confronted with a level of violent racism that stunned them, even after they had survived clashes with dogs and the water hoses of Alabama sheriffs. At several protests, some white onlookers, including members of the American Nazi Party, met Dr. King and Mr. Jackson with racial epithets, Confederate flags, rocks, bricks, bottles and swastikas.

“I’ve never seen anything like it my life,” Dr. King said after a march, according to Jonathan Eig’s biography, “King: A Life.” “The people of Mississippi ought to come to Chicago to learn how to hate.”

For Dr. King and Mr. Jackson, Breadbasket was an answer to a familiar problem faced by the civil rights movement, Taylor Branch, a chronicler of the movement, said in an interview.

“A lot of people would say, ‘Black people are suffering under long-term racial injustice,’” he said. “But how do you get anybody to pay any attention to it?”

Their solution rested on a theory: The public scrutiny from targeted boycotts would cost businesses customers and revenue, which would make it costly to discriminate in hiring and contracting, or in providing services.

“His methods in Breadbasket were more or less comparable to the sit-ins and the Freedom Rides,” innovations that tried to “draw attention to pervasive inequality that had always been there,” Mr. Branch said.

Mr. Jackson’s methods were not without controversy or criticism. Some questioned whether he had become too cozy with corporations, offering them favorable public relations at the expense of the working poor. Executives and some political conservatives objected to what they said were pressure campaigns that resulted in contracts for Mr. Jackson’s friends.

But the organizers of Operation Breadbasket were undeterred.

“We started with milk,” Mr. Deppe recalled. Organizers asked dairy companies to share annual employment data broken down by race.

“The C.E.O. at Country Delight said, ‘We are not about to let Negro preachers tell us what to do,’” Mr. Deppe remembered.

So the pastors stood in their pulpits and told congregants to stop drinking Country Delight.

“After three days, they came back to the table and agreed to 44 job openings, including 15 truck driver jobs,” he said. That agreement put $300,000 in Black people’s pockets a year, by Mr. Deppe’s estimate.

Mr. Jackson would apply those lessons to politics when he helped organize a 1982 boycott of a city festival after Chicago’s mayor, Jane Byrne, passed over several Black candidates for top department jobs and removed two Black school board members.

“Rev. Jackson led the marches on the lakefront where the mayor was wanting to do the big ChicagoFest,” said Jane Ramsey, who was a member of Mr. Jackson’s Rainbow PUSH coalition. Because the festival was such an important revenue source for the city, the marches hit the mayor where it hurt, she said, “and it brought visibility to the issues.”

Ms. Ramsey, 75, said the boycott helped lay the groundwork for Harold Washington’s campaign and election the following year as Chicago’s first Black mayor. She would serve in his administration.

Operation Breadbasket would influence people such as Marc Morial, the longtime chief executive of the National Urban League, who, like Mr. Jackson, fused politics and advocacy and saw a link between civil rights and economic issues.

“He knew you had to talk about corporate America and you had to talk about public policy,” Mr. Morial said of Mr. Jackson, “and that these are not individual issues.”

“He was able to bring some pressure and accountability to corporate America,” added Mr. Morial, who also served eight years as mayor of New Orleans. “At the time, corporations were benefiting greatly from the power of Black consumers but weren’t hiring African Americans and didn’t have any African Americans in the boardrooms.”

The demands of Dr. King and Mr. Jackson could be considered a forerunner to what would become known as diversity, equity and inclusion (D.E.I.) initiatives, which peaked following the police killings of George Floyd and other unarmed Black people in 2020.

Those efforts are now largely in retreat amid President Trump’s furious assault on what he calls anti-white bias. Mr. Trump has said that civil rights protections led to white people being “very badly treated.”

Representative Kweisi Mfume, Democrat of Maryland and a former head of the N.A.A.C.P., called the president’s success “amazing and alarming at the same time.”

The Trump administration and its political movement “are trying to find a way to do away with any semblance of diversity or inclusion or even expectation,” Mr. Mfume said.

Mr. Trump’s successes are not lost on the newest generation of civil rights leaders taking up the mantle from Mr. Jackson’s passing generation.

“It is heartbreaking to lose our Civil Rights Movement elders, our ‘Moses generation,’ in a moment where so much of their work and legacy is under attack,” Justin Jones, a young Tennessee state lawmaker, posted Tuesday on social media.

Justin Pearson, the other young Tennessean who leaped onto the national stage with Mr. Jones when both were expelled from the Tennessee legislature, called Mr. Jackson “unmovable and unwavering in his pursuit of justice.”

“And that’s the type of spirit we need to revive in our politics and in our communities and in our country right now,” he said.

But the tributes that poured in after Mr. Jackson’s death were not confined to his ideological allies.

The Black Conservative Federation, a network of Republican activists, posted, “Though we may not have always agreed with Rev. Jackson on politics or policy, we recognize and respect the depth of his commitment to the advancement of Black Americans and to the moral conscience of this nation.”

Audra D. S. Burch and Emily Cochrane contributed reporting.

Clyde McGrady reports for The Times on how race and identity shape American culture.

The post How Jesse Jackson Took King’s Civil Rights Movement to Company Doorsteps appeared first on New York Times.