Actors draw on what they know, Robert Duvall told Stephen Colbert in an interview that was broadcast in 2021.

“Your anger, your vulnerability — it’s got to be your temperament, without stepping out of that,” Duvall said.

So when filming a pivotal scene in “Network” (1976), in which his character, an executive, summarily fires the news chief played by William Holden, Duvall drew on his own experience of threatening to throw someone out. A producer on the movie, he told Colbert, had come to his dressing room to give him a note. “I didn’t like the guy,” Duvall explained, “and I said, ‘Would you turn around and walk out of this room?’” with an expletive added for good measure.

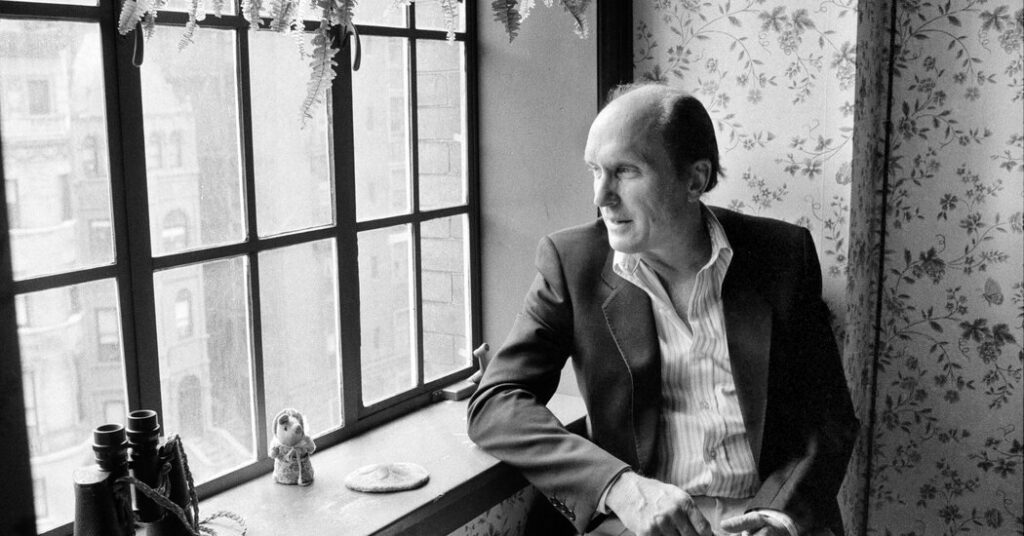

Duvall, who died on Sunday at 95, appeared in a number of classics. As his career crested in the 1970s, during a unique efflorescence in American cinema, he worked with auteurs like Robert Altman, Francis Ford Coppola, George Lucas and Sidney Lumet. In later decades, he appeared in the films of celebrated directors such as James Gray, Barry Levinson and Steve McQueen.

But Duvall, who directed five feature films himself, had a reputation — a proud one — of being testy with filmmakers. He believed that the directors who directed best also directed least. “I tend not to get along with too many directors,” Duvall told Colbert. “Get out of my way.”

Or, as he told the entertainment journalist Fred Robbins in 1984: “I have to have my freedom when I act. I like to be left alone — that’s it. Leave me alone, or hire somebody else.”

At least one director took Duvall’s opinions in stride. “He’s crazy, and that’s his strength,” Tony Scott, who directed Duvall in the Tom Cruise racecar movie “Days of Thunder” (1990), told the BBC. “He is difficult to handle, but he is brilliant. Since I worked with him, I’ve offered him every movie I’d done, but it’s just — — he’s a handful.”

As Duvall told interviewers repeatedly, his feeling that directors ought not to meddle with actors was less a question of ego than a sincere opinion that it was the way to the best performances.

“Most good directors will see what the actor will bring — otherwise you get a robot,” he said.

When he himself was directing, he told a round table of actors convened in 2010 by The Hollywood Reporter, “I try to turn the process around and let it come from them completely.” He added: “Because it’s their reality, because I don’t know them. It’s their history; I didn’t grow up with them.”

The freedom Duvall demanded extended to the words his characters spoke. There were times during the filming of “Tender Mercies” (1983), he told Robbins, when he wished to change lines from the script by Horton Foote — a friend of Duvall’s who also wrote one of the actor’s first movies, “To Kill a Mockingbird” (1962) — and the director Bruce Beresford wanted to keep it as it was.

“Beresford and I had it out about that,” Duvall recounted. “But anyway, it’s the final product that counts.”

The final product was Duvall’s Oscar for lead acting.

And “the ‘great’ Stanley Kubrick” — the implied scare quotes are his — “was an actor’s enemy,” he said at the 2010 gathering. He disliked the acting in “A Clockwork Orange” and “The Shining” — “they may be great movies but terrible performances.” Stories of the dozens of takes Kubrick would routinely require had reached him, and he did not approve. “How does he know the difference between the first take and the 70th take?” Duvall asked. “What is that about?”

When the actor Jesse Eisenberg recounted the director David Fincher’s shooting approximately 50 takes for a scene in “The Social Network,” Duvall’s face turned sour. Then he recalled his own good fortune, and smiled.

“I turned down a part in ‘Seven,’” Duvall said. “Maybe it was a good idea.”

Marc Tracy is a Times reporter covering arts and culture. He is based in New York.

The post Robert Duvall Had a Message for Directors: ‘Get Out of My Way’ appeared first on New York Times.