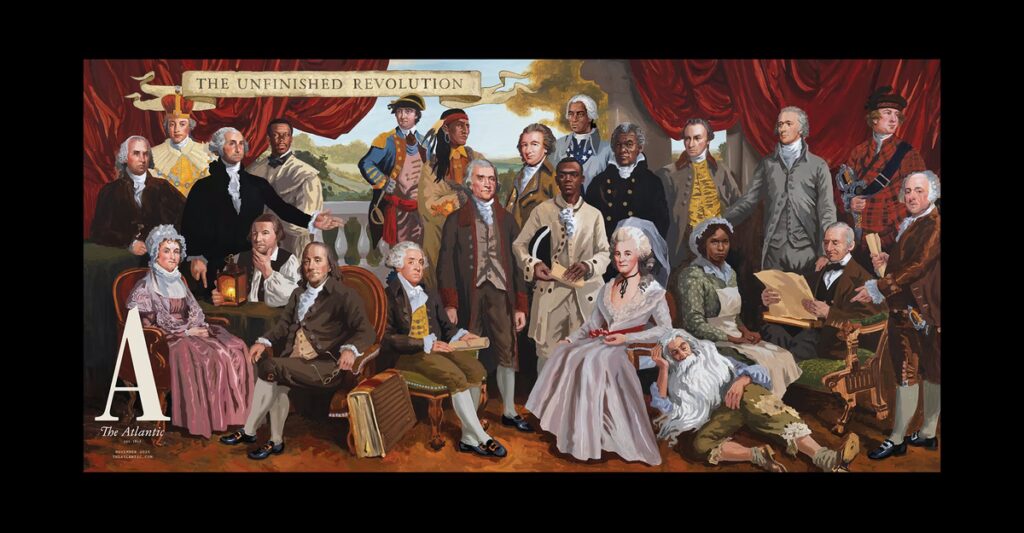

The Unfinished Revolution

The November 2025 issue examined the founding of the United States and brought the nation’s history to bear on its present—and its future.

I look forward to the cover of each issue of The Atlantic as much for the artistry as for the bold message it conveys. “The Unfinished Revolution,” however, struck me as, dare I say, revolutionary. I have the privilege of working with middle-school students, many of whom are learning about the American Revolution for the first time. Although we stress the importance of history’s “forgotten” heroes—in this case, the women, African Americans, and Native Americans without whom the efforts of the great men of the era would surely have failed—there are few, if any, images depicting them as equal to Washington or Jefferson. How inspiring for our young learners to see, in looking at Joe McKendry’s exquisite tableau, faces that reflect their own. I typically treasure old issues of The Atlantic, but this cover I’ll remove to display in a seventh-grade classroom.

Jenny Giessler Fairport, N.Y.

Rick Atkinson’s “The Myth of Mad King George” is a timely reminder that history is nuanced and rarely divides neatly between villain and victim. George III was not mad; he was methodical, conscientious, and tragically certain that duty and inflexibility were synonymous.

The American colonists’ decision to frame their rebellion as a quarrel with a man rather than a system was brilliant from a public-relations standpoint, if not exactly honest. By aiming their indictment at the King, the Founders converted constitutional disputes into a moral crusade. They could preserve their identity as Englishmen defending their rights even as they repudiated England itself. As Carl N. Degler wrote in Out of Our Past: The Forces That Shaped Modern America, the American Revolution was radical in its political outcome but socially moderate. It left intact many of the hierarchies it claimed to overthrow, because tyranny had been embodied in a single sovereign, not the structures that sustained him. Perhaps this helps explain why the Founders could prevent the radical promise of the Declaration from extending to African Americans and Native Americans.

Ethan S. Burger Washington, D.C.

I’ve long considered myself a patriotic progressive, so I greatly appreciated George Packer’s “America Needs Patriotism” and its lament over how many Americans have lost a love of their country. When I attended a recent “No Kings” march, I was surprised to see that by far the most ubiquitous symbol was the American flag. I saw big flags waving in the air, tiny lawn flags carried by moms and kids, flag bandannas, flags on T-shirts, and flags as capes, including one pinned with a sign that read This Flag is Anti-Fascist. Where was this constellation of red, white, and blue? San Francisco. This was quite a contrast to the 2003 peace marches against the U.S. invasion of Iraq, where an American flag among the protesters was as common as a necktie at a rock concert. Perhaps Donald Trump has had at least one salutary effect on American civic culture: He’s convinced even the left to embrace the Stars and Stripes.

Jason Dove Mark Bellingham, Wash.

George Packer implies that the left is as culpable as the Trumpian right for deep skepticism about expressions of patriotism. But he seems to conflate three different positions: (1) belief in core values such as liberty, equality, and democracy; (2) flag-waving support for, or loyalty to, one’s own country; and (3) a belief in America’s “essential decency.”

It is perfectly reasonable to be skeptical of nationalism—to be, as Thoreau put it, citizens of the world first, “and Americans only at a late and convenient hour.” You don’t have to believe America is decent; you can be critical of the disturbing and sometimes horrific qualities that America has represented over much of its history but still offer a full-throated defense of democracy, equality, and other values that should be aspirational for people everywhere.

Alfie Kohn Belmont, Mass.

As the president and CEO of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation at the time of the 1994 slave auction, I took particular interest in Clint Smith’s article, “What Is Colonial Williamsburg For?”

The idea of reenacting a slave auction originated with Colonial Williamsburg’s African American Interpretation Department, whose director, Christy Coleman, approached the foundation’s leadership and said that her team was not only ready to put on the reenactment, but wanted to do it. Knowing that it would be controversial, we agreed that the reenactment would be based on records of actual slave auctions conducted in Virginia during the period, and that we would make it part of our educational programming. I gave her team my blessing.

On the morning of the program, after The New York Times published a story about our plans, representatives from the Virginia branches of the NAACP and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, as well as local ministers and others who wanted the reenactment canceled, asked to meet with me. I listened carefully and told them that I appreciated that they had come. I explained that the reenactment was something that our African American–interpretive staff wanted to do, that we thought it was the right thing to do, and that we had committed to the staff and the public that we were going to do it. I reminded them that our mission was educational—we were doing this not to sell tickets, but to teach.

They listened but told me that they still planned to attend and protest. Several blocked the stage before the program began, but when the audience of 2,000 began to boo, all except one protester stepped down. Christy and her colleagues worked the program around him. The other protesters remained silent.

We did the slave auction only once; it was simply too emotional an experience for the staff. I fielded some complaints from donors, and lost a few, but never regretted the decision. It was the right thing to do.

Robert C. Wilburn Pittsburgh, Pa.

I was particularly interested in John Swansburg’s article on “Rip Van Winkle” because Cornelius S. Van Winkle—who originally published Washington Irving’s The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent.—was the brother of my great-great-great-great-grandfather Peter Van Winkle.

Family lore has it that Irving got into some sort of heated disagreement with Cornelius, and got revenge by bestowing the Van Winkle name on his main character—a man unflatteringly described as having, among other things, an “insuperable aversion to all kinds of profitable labor.”

While I have no idea if there’s any truth to this hilarious tale, it’s worth noting that my Van Winkle ancestors were among the first Dutch settlers in this country, having arrived less than two decades after Henry Hudson sailed upriver in 1609. They came to live in present-day Albany, Rensselaer, and Hudson and Bergen Counties. I’ve always been proud to trace my roots directly back to the founding of our great nation, regardless of my connection to its founding folktale. In his article, Swansburg writes that, by the end of the story, Rip has “become a link to the past, a living connection to the history that predates the Revolution.” I look forward to rereading “Rip Van Winkle” and once again hearing what he has to say.

Christopher Pollock Brooktondale, N.Y.

Two days after we received the November issue, my wife, Cindy Whitman, a retired history teacher, completed a diorama version of Joe McKendry’s cover painting. She customizes Playmobil figures and found objects to make scenes to display in libraries and children’s museums.

Dave Whitman Queensbury, N.Y.

Behind the Cover

In this month’s cover story, “What’s the Worst That Could Happen?,” Josh Tyrangiel reports on how artificial intelligence will change the American job market. The new technology has the potential not just to make workers more efficient, Tyrangiel argues, but to render many of them obsolete. For our cover image, the artist Stephan Dybus evoked both the marvels of AI and a looming threat for which the American economy, and democracy, may not be prepared. — Paul Spella, Senior Art Director

This article appears in the March 2026print edition with the headline “The Commons.”

The post Seeing Ourselves in America’s Unfinished Revolution appeared first on The Atlantic.