“The whole world comes to Nantucket,” my mother is fond of saying about the island I’ve called home for the last 12 years. With international visitors surging every summer with the tide, I hardly felt the need to return the favor to the whole world. I felt content exploring my local library.

But on my 38th birthday, something changed. I began to feel an unfamiliar sense of wanderlust. Suddenly, I wanted to make up for lost time.

When I made plans to visit friends in Berlin last fall, I aimed to learn a little German — enough to read signs, order a drink, maybe check out a dating profile. I downloaded the ubiquitous Duolingo; other American friends loved it.

But after a few weeks, I didn’t feel as if I was learning much at all. Duolingo wanted me to learn sentences that would never come up on a European vacation. In what scenario would I need to know how to buy five kilograms of potatoes?

Also, the Duolingo app lives on your phone, like an ever-present tutor waiting to teach you. It’s convenient, but perhaps too available. Where’s the romance in that?

I knew I had to break up with that cute Duolingo owl, but what was the alternative? I headed to the library to search for introductory German textbooks.

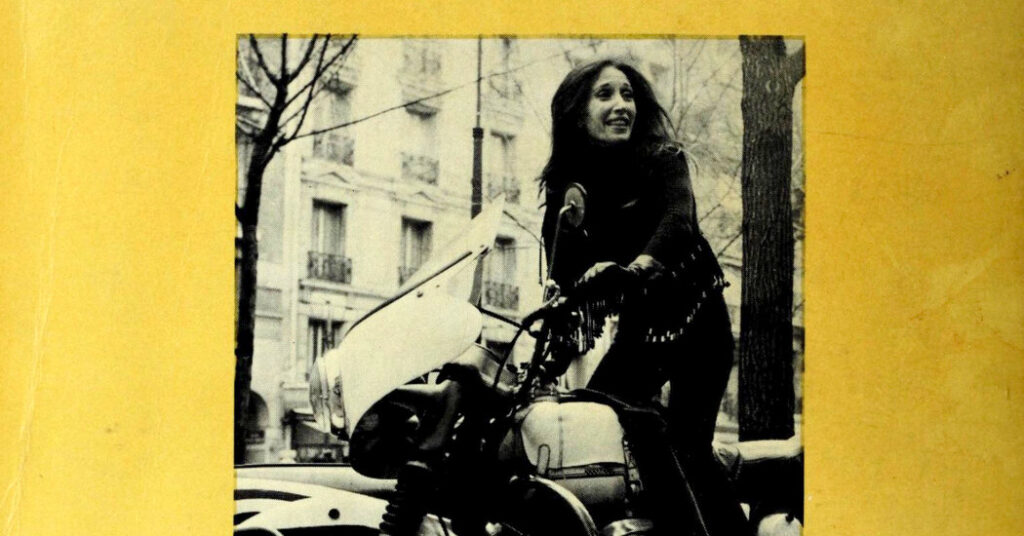

One, available via interlibrary loan, jumped out at me: Adrienne Penner’s “German in 32 Lessons,” published in the United States in 1978 by W.W. Norton as part of its “Gimmick” series. Credited only as Adrienne, the writer, a fringed-biker-jacket-clad Parisian, practically reached out of her author photo and invited me to take a ride on her motorcycle. Très chic (I mean, sehr schick).

I happily time traveled with Adrienne to West Berlin circa 1978, where I spent the weeks before my trip translating phrases like “It’s his broad who makes him so nervous,” “I think he’s single because he lives with his mother,” and “She tore up his letter two weeks ago.” Here was the intrigue I’d been hoping for. Not buying potatoes, but peeling away the layers of a romance gone awry.

Duolingo did not like being ghosted. It nagged, sending alerts and emails as the days wore on: “Mary, I’m not above begging. Do your lesson, put my heart at ease!” But Adrienne didn’t chase me; she was too cool for that.

Each lesson crackled with lines that could easily make up the spare script of a lost Sam Shepard play: “The unsuccessful writer lives in a small, cheap room,” “He doesn’t see me on purpose,” “All dreams don’t come true.” There were no points, no streaks, no cartoon characters, just me and the penciled-in notes in the margin from the last person who borrowed this book from the Osterville Village Library.

After two months of following Adrienne’s lessons, I knew enough German to order a drink and to ask to turn up the music. I’d figure out the rest on the plane.

At Villa Neukölln, a movie theater turned bar on Hermannstrasse, I drank alkoholfrei beer by candlelight as the young Berliners at the next table over dissected a bad breakup in alternating hushed tones and rising voices. I understood them not because I had mastered German, but because, partly thanks to Adrienne, I could understand failed relationships.

“The psychology of a people is reflected in the vitality of its language,” Adrienne wrote in the preface to “Der Gimmick,” another of her language instruction books, which were available for French, Spanish, German and Italian. In these books, “gimmicks,” essentially, are useful (or maybe not so useful) phrases. “Wherever I am,” Adrienne wrote, “I need to be able to say, ‘in jail,’ ‘it’s now or never,’ ‘he drinks like a fish,’ ‘a cop,’ etc.” The series carried blurbs by literary and cultural heavyweights of the day: the French novelist and screenwriter Françoise Sagan, the “Barbarella” director Roger Vadim and the novelist Henry Miller all sang Adrienne’s praises on the back covers.

Could Adrienne really have been this cool, or was she some public relations invention? Her editor at W.W. Norton has since died, and the records of Flammarion, her books’ French publisher, didn’t go back that far. A family tree on an online genealogy website led me to the New York Public Library’s American Jewish Committee Oral History Collection, where a 1991 interview with Adrienne’s father, Saul Penner, shed some light on my mystery. Though Saul focused mainly on his career as a physician, his fatherly pride in Adrienne is frequently on display.

Saul told the interviewer that Adrienne went to Paris without any knowledge of the language, took a rapid-fire course and now spoke fluent French. “She’s not married,” he continued. “I can’t get her to settle. … She’s got a lot of boyfriends. … I wrote to her only recently again: ‘Please think about settling down,’ and so forth, but so far I haven’t succeeded.”

Aha! Adrienne was real. She’d mastered a language and been a successful writer, all as a single woman in her late 30s. It wasn’t too late for me.

I channeled Adrienne’s boldness in Berlin, walking over solo from my efficiency apartment to the Wild at Heart bar on Wiener Strasse, speaking broken German as I paid the doorman. Wild at Heart was a fabulous dive, with Johnny Cash and Elvis portraits on the walls. The whole place glowed red and most everybody was smoking cigarettes, like something out of the David Lynch movie of the same name. I would not have been surprised to see tumbleweeds.

The band had a hypnotic hold over its audience, who sang along in German to every word. I was impressed that this local band seemed to have such a devoted fan base. I later discovered they were a tribute band for Die Ärzte (think a German version of Green Day) and not just dads with rock-star dreams.

They say you only need two chords, if they’re the right chords. Maybe it’s the same with words, at least to start. You can get pretty far with variations on bitte and danke. You can read and study, but there is no substitute for listening to people speak (or sing) a language all around you.

It also turns out there are a few English terms that just sound better in English: “baby,” “party,” “yeah-yeah-yeah” and “rock ’n’ roll.”

Adrienne’s trail went cold after the interview with her father. I don’t know where her life eventually took her — to raucous bars like this one or to settling down and marriage, as her dad had implored her? In the words of Adrienne: “All dreams don’t come true.”

I knew something had shifted inside me as I cruised down Hasenheide on a borrowed bicycle and started wondering what it would be like to ride a motorcycle. There was still time. When I got back home, I found myself eyeing fringed leather jackets at vintage shops and planning my next trip far away from the island.

As Adrienne might have said, “It’s now or never.”

Follow New York Times Travel on Instagram and sign up for our Travel Dispatch newsletter to get expert tips on traveling smarter and inspiration for your next vacation. Dreaming up a future getaway or just armchair traveling? Check out our 52 Places to Go in 2026.

The post I Dumped Duolingo for a German Teacher in a Biker Jacket appeared first on New York Times.