Something strange is happening on the left. Signs of peace are emerging in the long civil war over economic policy between the progressive and moderate wings of the Democratic Party. In the past two months, a prominent group from each of the two factions has produced its own report on how to win back working-class voters—a problem that, notwithstanding Democrats’ strong results earlier this month, has grown more acute since Donald Trump was first elected, in 2016. The result, far from a battle of dueling worldviews, is a surprising amount of consensus. Although they might not put it this way—and although fierce debates still rage over cultural differences—members of the far left and the center seem to have concluded that, for Democrats to win elections, each side needs to become more like the other.

The first report, “Democrats’ Rust Belt Struggles and the Promise of Independent Politics,” was produced by a constellation of progressive organizations and labor groups—some of which were founded to channel the energies of the 2016 Bernie Sanders campaign—along with the socialist magazine Jacobin. And yet the report does not call for classic Sandersian policies such as Medicare for All and universal child care; indeed, it warns against big redistributive government interventions. Its authors point out that such programs are “often met with skepticism by working-class voters, who may distrust government-administered systems they perceive as inefficient, overly bureaucratic, or disproportionately benefiting others.” This will sound obvious to some readers, but coming from the Bernie left, it’s a major concession.

The report argues that Democrats should focus instead on policies that directly lower costs, rein in excessive wealth, and shape how resources are distributed in the first place—often referred to as “predistribution.” To that end, it recommends such progressive but non-radical ideas as capping drug prices, raising taxes on the superrich, upgrading the country’s infrastructure, and cracking down on corporate price gouging. “These are the kinds of policies that align most closely with working-class values,” Jared Abbott, the director of the Center for Working Class Politics and a lead author of the “Rust Belt Struggles” report, told me. “It’s this sense of, We don’t just want a handout. We want to be able to provide for our families and have the dignity and respect that comes with that.”

“Deciding to Win” ends up in a similar place, starting from the opposite direction. Democratic moderates have long been associated with such technocratic ’90s-style ideas as means-tested programs, business tax credits, and deregulation. But the report—which drew input from über-establishment Democrats including James Carville, David Axelrod, and David Plouffe—concludes that many of these policies are political losers. So, too, are some of the buzzier new centrist-coded policies, such as loosening land-use regulations, paring back environmental-review laws, and subsidizing electric-vehicle purchases.

Meanwhile, the moderate report’s list of Democratic proposals worth running on is full of ideas well to the left of even Barack Obama’s agenda, including many of the same policies recommended by the “Rust Belt Struggles” report as well as other longtime progressive priorities, such as universal paid family leave. “Don’t get me wrong: This isn’t exactly a socialist wish list,” Simon Bazelon, the lead author of the report, told me. “But I think it may come as a surprise to everyone just how much there is for progressives to like in here.”

[David A. Graham: Are the Democrats overthinking this?]

After the 2016 election, Democrats plunged into a prolonged struggle between a socialism-curious left in favor of Medicare for All, a Green New Deal, and free college, and moderate capitalists who preferred tax credits and means-tested programs. That clash of big, sweeping ideologies is nowhere to be found in these reports.

How did two camps with such different worldviews arrive at such similar recommendations this time around? The answer may be that both groups were committed to figuring out what policies are actually popular among voters. This is surprisingly rare in politics. During the 2020 Democratic primary, leftists and centrists tended to assert that their ideal policy agendas also happened to be beloved by the public; both groups cited their own carefully selected polls as evidence. This gave the impression that almost every Democratic policy was, somehow, widely popular with voters.

In recent years, however, an emerging body of evidence has found that single-issue polls—in which a pollster asks, for example, “Do you support Medicare for All?”—tend to greatly overestimate real-world voter support. (This is in part because so many of them are commissioned by advocacy groups for the purpose of pushing a particular agenda.) Policies that garner supermajority support in polls, such as universal background checks and school-choice laws, regularly fail to gain even a simple majority when they appear on the ballot.

To avoid those traps, the authors of both reports used more rigorous methods in an effort to figure out which policies actually resonated with voters. “Deciding to Win” gave respondents the kind of context they would likely get if the idea were proposed in the real world, such as which party tends to favor it, the arguments for and against, and how much it would cost. “Rust Belt Struggles” required voters to rank different policies against one another to determine their relative popularity. By doing that, the groups ended up with a more credible picture of how voters might respond to Democratic policies in the context of an election.

The reports converged not only on policy specifics but on how Democrats should talk about economic issues. On this point, the party has long been divided between economic populists such as Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, who tend to rail against corporations, billionaires, and the system more broadly, and economic pragmatists including Obama and Joe Biden, who prefer the more positive-sum language of equality, fairness, and opportunity. But the report from the party’s moderate wing ends up endorsing the populist approach—which in 2025 means a focus on affordability for ordinary citizens, and strong criticism of powerful individuals and corporations that benefit from the status quo.

“In our view, the case for a more anti-establishment posture is strong,” the “Deciding to Win” authors write, citing reams of evidence showing that majorities of voters are dissatisfied with the state of the country, distrusting of institutions, and convinced that the economic system is rigged in favor of the wealthy. In that kind of political environment, Democratic messaging centered on concepts such as the American dream and Kamala Harris’s “opportunity economy” has become out of touch. “Deciding to Win” suggests that even those who propose a more moderate economic agenda should embrace populist rhetoric to tap into these prevailing attitudes. “Being moderate does not mean running on a defense of the political establishment, elites, corporate interests, or the status quo,” the report argues. “It also does not mean having a mild-mannered temperament or taking the centrist position on every issue.”

The convergence on both policy and rhetoric is already beginning to occur in the real world. The latest policy agenda released by the congressional Progressive Caucus calls for raising the federal minimum wage and extending federal drug-price negotiation, but doesn’t mention Medicare for All or universal child care. Moderates, meanwhile, have begun to sound a lot more like their progressive counterparts. In her successful campaign for governor, New Jersey’s Mikie Sherrill, a centrist, adopted distinctly populist themes, including a utility-rate freeze. She touted an “affordability agenda” that promised to lower prices by going after “health care middlemen who make your prescriptions unaffordable, the monopolies that hike up mortgage and rental prices, and the grid operators who continue to raise energy costs without accountability.”

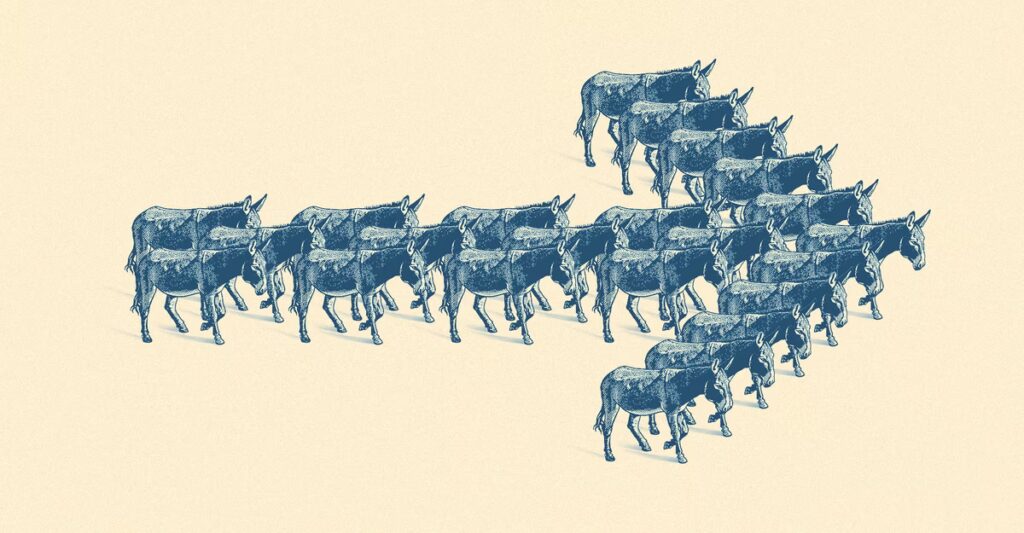

If the Democratic Party appears to be marching toward something of a big-tent consensus on economics, disagreement remains over how to approach social and cultural issues.

According to the moderates, the root cause of working-class disaffection with the Democratic Party is the fact that the party swung too far to the left on issues such as crime and immigration. “Deciding to Win” notes that, as Democrats have taken more progressive positions on a range of social and cultural issues over the past decade, the number of voters who say the party is “too liberal” has spiked, voter trust in Democrats on these issues has plummeted, and voters who self-identify as ideological “moderates” and “conservatives” have abandoned it. “When you put all of this together, it tells a really clear story,” Bazelon told me. “The Democratic Party has moved significantly to the left on a number of issues that are important to voters, and lots of voters have moved away from our party in response.” The only way to win back these voters, the report concludes, is for Democrats to adopt more conservative cultural and social stances that may infuriate their base but align with the views of working-class voters in a general election.

[Jonathan Chait: Democrats still have no idea what went wrong]

This approach, the moderates argue, has worked in the past. In 1992, Bill Clinton ran as a tough-on-crime Democrat and went out of his way to distance himself from left-wing racial-justice advocates. While running for president in 2008, Obama refused to support gay marriage, and throughout his presidency clashed with immigration advocates who considered his positions to be overly restrictionist. “It’s extremely difficult to find examples of Democratic candidates who win in swing districts without taking more conservative positions on some issues—particularly immigration and crime,” Bazelon told me. “Over and over again, the candidates we see winning tough races do so by breaking with the national party.”

Many on the left have a different view. “Even on issues like immigration, populists don’t need to ape Trump to win Rust Belt voters,” the “Rust Belt Struggles” report declares. Although it acknowledges that some voters may think the party is too far left, it argues that “the cultural critique of the party is ancillary to many voters’ core criticism: that the party is beholden to elites, doesn’t deliver, doesn’t listen, and doesn’t fight.” So long as Democrats adopt a relentless eat-the-rich message, recruit working-class candidates who embody genuine anger at the status quo, and offer policies that speak to voters’ real material concerns, this theory holds, they can win over those voters without needing to substantively change their positions on social issues.

The progressives have their own examples. They point out that Bernie Sanders is the most popular politician in the Democratic Party. A less obvious but perhaps even more important case study is Dan Osborn, a 2024 independent U.S. Senate candidate who nearly upset a Republican incumbent in Nebraska, a state that Trump won by 20 points, by running on an aggressive economically populist message. “What we think is vital about them is that they exude a kind of populist anger,” Abbott, the “Rust Belt Struggles” report’s lead author, told me. “They aren’t just saying the words. This is deep in their bones. They’re pissed off; they’re fed up. People relate to that. It’s more important than even the policies.”

Here, the weight of the evidence supports the moderates. Osborn himself ran as not just an economic populist but an immigration hawk. His 2024 campaign ads, for instance, featured lines such as “Social Security to illegals? Who would be for that?” and “If Trump needs help building the wall, well, I’m pretty handy.” Sanders, too, has routinely taken immigration stances that make many on the party’s left uncomfortable, including calling open borders a “Koch Brothers proposal” during his 2016 campaign and more recently praising Trump’s approach to the border.

[Marc Novicoff: Democrats don’t seem willing to follow their own advice]

Still, the fact that this is the central debate among Democrats is revealing. The first time Democrats lost to Trump, in 2016, the party plunged into a grueling battle over economic ideology that pitted democratic socialism against reforming capitalism. Democrats still have their share of disagreements. But, for the time being, they might actually have managed to find an economic message they can agree on.

The post Leftists and Moderates Are Trying to Be More Like Each Other appeared first on The Atlantic.