The Rev. Jesse Jackson, a charismatic preacher who became the leading voice of Black American aspirations in the years after the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and was the first African American to gain significant traction as a presidential candidate, died Tuesday. He was 84.

A statement from his family did not provide cause of death.. Rev. Jackson had initially been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in 2015. Years later, he learned he had progressive supranuclear palsy, a neurological disorder that affects movement.

At the height of his influence, Rev. Jackson was widely regarded as the nation’s preeminent civil rights leader, a ubiquitous presence before the television cameras. He showed up at protests and marches across the country to champion civil rights and social justice. And when civil disorder broke out — as it did after King’s assassination in 1968 and, decades later, after the fatal police shooting of 18-year-old Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014 — he urged restraint and nonviolence.

In the late 1970s, he began to expand his activities beyond the United States. He thrust himself into Middle East peacemaking, prisoner-release efforts and the movement against apartheid in South Africa, and he was regularly seen in the company of presidents and foreign leaders.

He was ordained as a Baptist minister but never had his own church, preferring the wider stage of civil rights activism. At 6-foot-2, with the power and fluid grace of an athlete, he was a commanding presence wherever he went. As a public speaker, he was electrifying.

Rev. Jackson’s oratorical style, like the civil rights movement, was rooted in the Black churches of the South. He would begin slowly, in an almost conversational tone, and gradually build to a crescendo that left some listeners in tears.

On Saturday mornings in Chicago, he would lead a crowd of devoted followers in his signature chant, often broadcast live on local and national radio. It began something like this:

“I am — somebody.

“I may be poor, but I am — somebody.

“I may be on welfare, but I am — somebody.

“I may be uneducated, but I am — somebody.

“I may be in jail, but I am — somebody.”

Rev. Jackson’s message to Black Americans was largely one of self-help. “Keep hope alive,” he would say. Or, “You may be in the slum, but the slum doesn’t have to be in you.” Or, “Freedom ain’t free.”

His drive and passion also brought him detractors. At times, he annoyed King, and he feuded with other King aides, some of whom considered him a shameless self-promoter.

Like many who knew him well, Roger Wilkins found Rev. Jackson both inspiring and exasperating. As an editorial writer for The Washington Post in the 1970s, Wilkins had to deal with Rev. Jackson as a frequent, and often uninvited, visitor.

“He would just show up,” Wilkins said. “It was, ‘Rev. Jackson with Dr. So-and-So is downstairs to see you.’ He wanted his name in the paper.”

In 1968, Wilkins, as a young African American official in the Justice Department, walked the streets of Washington amid the rioting that followed King’s assassination. He made his way to 14th Street NW, where Rev. Jackson was speaking to an angry crowd.

“It’s not Black pride to burn down a Black man’s store,” Wilkins recalled Rev. Jackson saying. After a while, the anger subsided, and the crowd began to drift away. “I saw it with my own eyes,” Wilkins said. “He really did preach the violence out of those people.”

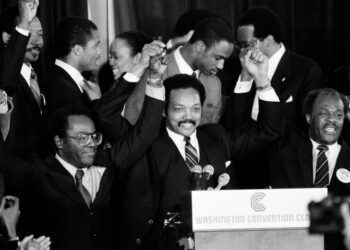

Rev. Jackson ventured where no civil rights leader had gone before by seeking the 1984 Democratic presidential nomination. He was widely viewed as a gadfly with no chance of winning. By all accounts, his poorly funded campaign was the most chaotic and disorganized of the modern era.

He amassed more than 3 million votes during the primaries, and he took 384 delegates with him to the Democratic National Convention in San Francisco. From an initial field of eight candidates, he finished third in the primary campaign, behind former vice president Walter F. Mondale, the eventual nominee, and Sen. Gary Hart of Colorado.

“When they write the history of this [primary campaign], the longest chapter will be on Jackson,” Mario Cuomo, the New York governor, said to The Post at the time. “The man didn’t have two cents. He didn’t have one television or radio ad. And look what he did.”

Four years later, Rev. Jackson again sought the Democratic nomination. He was better financed and organized, and he easily improved on his 1984 results. He won about 7 million votes, including 12 percent of White voters.

When he won the Michigan caucuses in 1988, he briefly became the leader in the nomination race. He went to the party’s national convention in Atlanta with more than 1,200 delegates, second only to the eventual nominee, Michael S. Dukakis, the Massachusetts governor. He had gone further than any Black person in American presidential politics until that time, a generation before Barack Obama sought and won the White House in November 2008.

“My race was never about running for the White House alone,” Rev. Jackson told journalist Barbara A. Reynolds, author of a Jackson biography. “It was about 10,000 people running in their states, for school board and sheriff and state legislatures, running for Congress and mayor and governor.”

Rev. Jackson was among the throng of Obama supporters who participated in the victory celebration in Chicago’s Grant Park, and his wellspring of tears was noticed by reporters.

He explained the next day to NPR: “Well, on the one hand, I saw President Barack Obama standing there looking so majestic, and I knew the people in the villages of Kenya and Haiti and mansions and palaces in Europe and China were all watching this young African American male assume the leadership to take our nation out of a pit to a higher place.

“And then, I thought about who was not there: Medgar Evers, the late husband of sister Myrlie. There’s Schwerner, Goodman and Chaney, two Jews and a Black killed in Philadelphia, Mississippi. And Jimmie Lee Jackson. So the martyrs and the murdered whose blood made last night possible. I could not help but think this was their night.

“And if I had one wish, if Medgar or if Dr. King could have just been there for a second in time, it would have made my heart rejoice. And so, it was kind of the dual thought of his ascendance in leadership and the price that was paid to get him there.”

A fast start

Jesse Louis Burns was born in Greenville, South Carolina, on Oct. 8, 1941. His mother, Helen Burns, was a 16-year-old high school student. His father, Noah Robinson, was a cotton grader and a respected member of the community. He lived next door and was married to another woman.

About two years after giving birth, Helen Burns married Charles Jackson, a postal worker who adopted Jesse. At all-Black Sterling High School, Jesse Jackson was a good student and an outstanding athlete. He was the starting quarterback, the class president and the student body president.

His athletic ability won him a scholarship to the University of Illinois, but he left after a year, in 1960. For years, he maintained that he quit Illinois because the coaches told him that they would not play a Black student as quarterback. Years later, reporters discovered that the Illinois quarterback at the time was another African American, Mel Meyers.

He transferred to North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College (now North Carolina A&T State University), a historically Black institution in Greensboro, where he thrived. He was the starting quarterback on the football team and student body president.

The civil rights movement was gaining momentum during Rev. Jackson’s college days, and it was then that he had his first experience of social activism, leading student protests in Greensboro. He also met Jacqueline Brown, whom he married in 1962.

Rev. Jackson graduated in 1964 with a bachelor’s degree in sociology and accepted a Rockefeller Foundation grant to attend Chicago Theological Seminary. He did not complete his studies there, leaving after two years to devote himself to civil rights work. (He was ordained in 1968 by the minister of a Chicago church.)

Rev. Jackson liked to point out an ironic footnote to his reputation as a compelling orator. At the seminary, his final grade in preaching was a D. The course required that students write their sermons in advance, but Rev. Jackson insisted on simply rising in class and beginning to speak.

“He’s a very brilliant guy. But undisciplined,” the Rev. Victor Obenhaus, Rev. Jackson’s faculty adviser, later told the New York Times.

Like so many in his generation, Rev. Jackson was drawn into the civil rights movement by King. They met in 1965 when Rev. Jackson and other seminary students traveled to Selma, Alabama, for what turned out to be a historic march for voting rights.

From the beginning, Rev. Jackson made clear that he did not intend to fade into the crowd. Outside a church in Selma, members of King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference staff were addressing assembled marchers, when “up popped Jesse,” an unknown newcomer, to deliver an impassioned speech, one witness recalled.

“He immediately took charge,” Andrew Young, then a top deputy of King’s and later U.S. ambassador to the United Nations and mayor of Atlanta, recalled to the Times. “It was almost like he came in and, while people were lining up, he wouldn’t get in line. He would start lining people up.”

The aggressive young man impressed King, who accepted Rev. Jackson’s offer to work as an SCLC organizer in Chicago. Within months, King named him national director of Operation Breadbasket, an SCLC campaign that pressured businesses to hire and promote Black workers.

Rev. Jackson’s assertiveness soon created tension with other senior King aides. King, too, eventually became exasperated with the brash young activist, once telling him, “If you want to carve out your own niche in society, go ahead, but for God’s sake don’t bother me.”

King assassinated

On April 4, 1968, King was shot by a sniper as he stood on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis. Rev. Jackson was in the motel courtyard at the time. His actions over the next several hours drove a deeper wedge between him and other King aides but also served to propel him toward national prominence.

Rev. Jackson immediately returned to Chicago. Dressed in the bloodstained turtleneck shirt he had worn in Memphis, he arranged to be interviewed on local television programs and NBC’s “Today” show, telling reporters that King died in his arms.

Rev. Jackson’s conduct and his account of King’s last moments infuriated the other aides, who vehemently denied his version of the events. Rev. Jackson always defended his actions, which, whatever his intentions, elevated his public profile. In April 1970, Time magazine put an image of Rev. Jackson on the cover of a special issue on Black America.

There was tension between Rev. Jackson and the Rev. Ralph Abernathy, King’s successor as head of the SCLC, and eventually a complete rupture in their relationship. In 1971, the SCLC board suspended Rev. Jackson for 60 days for “administrative impropriety” after he organized trade fairs for Black businesses in Chicago without consulting the SCLC’s national leadership.

Rev. Jackson resigned from the SCLC and, in December 1971, announced the formation of a new civil rights organization, Operation PUSH — initially People United to Save Humanity, later renamed People United to Serve Humanity.

Operation PUSH and PUSH Excel, an affiliate that sought to help Black students in inner-city schools, became the main vehicles by which Rev. Jackson carried his message to the country.

He traveled tirelessly to city schools around the country, exhorting disadvantaged students to do their homework, avoid drugs and work hard. But the PUSH Excel campaign to lift struggling urban schools in the late 1970s, like many similar efforts over the years, was beset by administrative woes and forces beyond its control such as school district budget cuts. For his part, Mr. Jackson may have depended too much on his inspirational powers to drive strong results.

“I assumed that if we could provide the motivation to get kids into the schools and ready to work, then the schools would take over from there,” he told the Times in 1981. He said he saw his role as fostering self-discipline and ambition by holding student rallies with mottos such as “Down with dope. Up with hope.”

“I learned that it’s not that simple,” he said.

Rev. Jackson added: “I’m not an educator; I’m a preacher. I keep coming back to the Parable of the Sower. Some of the seeds fell on the stony ground, and some among thorns, and some fell on the good soil and germinated. But even when a seed takes root, you got to wait.”

Meanwhile, Operation PUSH won concessions from Coca-Cola and other companies that it threatened with boycotts unless they agreed to hire more African Americans and do more business with Black-owned vendors.

But critics said that PUSH’s boycott threats differed little from extortion and that some of the Black businesspeople who benefited from the PUSH campaigns were major donors to Rev. Jackson’s causes. Some business executives — White and Black — praised Rev. Jackson’s conduct in their negotiations with him. Others said they felt like victims of unseemly tactics.

“It’s a shakedown,” T.J. Rodgers, then president and chief executive of Cypress Semiconductors in San Jose, told the Los Angeles Times in 2001. “The basic shakedown mechanism is, he declares racism based on dubious statistics. Then he gives you a chance to repent — and the basic way is to give Jesse money. The threat is you’ll be labeled a racist if you don’t. That scares business leaders.”

In 1990, Post columnist William Raspberry wrote critically of Operation PUSH’s call for a national boycott of athletic-wear giant Nike unless the company did more to advance the economic interests of African Americans.

PUSH contended that Nike should be promoting more African Americans to its executive ranks and doing more business with Black-owned companies. It also assailed Nike for running ads that induced poor Black youths to pay exorbitant prices for sneakers endorsed by basketball star Michael Jordan.

“Like so many of the affirmative-action proposals, it amounts to a bait-and-switch game,” Raspberry wrote. “The inner-city poor furnish the statistical base for the proposals, but the benefits go primarily to the already well-off. … What does it do for the poor for Nike to hire an upper-middle-class Black executive from another company to be a vice president at Nike, or to give [civil rights leader and business executive] Vernon Jordan another seat on a corporate board?”

Over a dozen years, Mr. Jackson’s organizations received about $17 million in government grants and private donations. Audits and other evaluations of the programs found that they were often in chaos, with poor management, little follow-through and weak financial controls.

One reason for the dysfunction, according to people who worked closely with Rev. Jackson, was that he prized loyalty above all else, including competence. “Loyalty, absolute loyalty, was always the most important thing to him, not whether you could do the job,” a former PUSH official told the Los Angeles Times in 1987.

“The problem with Jackson’s program … was his inability to sustain its momentum when he was not present, its dependence on his charisma,” Joseph A. Califano Jr., secretary of health, education and welfare under President Jimmy Carter, wrote in his 1981 book “Governing America.”

Rev. Jackson shrugged off such criticism.

“I’m a tree shaker, not a jam maker,” he would say.

Expanding mission

Personal charisma was the foundation of Rev. Jackson’s public life.

Over the years, he expanded his mission into some of the world’s most volatile regions. In early 1984, as he began his first presidential run, he traveled to Damascus, Syria, and achieved what American diplomacy had failed to do: He gained the release of Lt. Robert O. Goodman Jr., a Navy aviator who was shot down over Lebanon and taken prisoner by Syrian forces.

Other successes followed. Later in 1984, Rev. Jackson visited Cuba, where Fidel Castro released 23 American and Cuban prisoners. During the Persian Gulf War buildup in 1990, Rev. Jackson traveled to Iraq and played a role in persuading Saddam Hussein to release dozens of British and U.S. nationals.

In 1979, at the invitation of South African church groups, Rev. Jackson made a high-profile visit to that country, then under apartheid. In a stop at a squatter camp, he led thousands of the country’s most disadvantaged in his chant of Black consciousness and pride: “I may be poor, but I am — somebody!”

Six years later, he was among the anti-apartheid demonstrators arrested at the South African Embassy in Washington, and he continued to push for U.S. corporate and college disinvestment while the racist regime remained in power.

“Every investment in South Africa is another brick in the fortress wall that protects that system,” he told the New York Times. “The universities have substantial investments there, but more significant, they lend credibility to the apartheid system with those investments.”

In 1999, he went to Belgrade, Serbia, and negotiated the release of three captured U.S. soldiers who were reported to have served with a U.N. peacekeeping unit and NATO forces during the conflict in Kosovo.

Rev. Jackson’s international forays were often controversial, especially when they involved the Middle East. He visited the region in 1979 and was photographed embracing Yasser Arafat, head of the Palestine Liberation Organization. It was later disclosed that between 1978 and 1981, PUSH affiliates received $200,000 in donations from the Arab League, a confederation of Arab countries and the PLO.

Then, early in the 1984 campaign, Post journalist Milton Coleman reported that in a conversation with him, Rev. Jackson had referred to Jews as “Hymies” and to New York City as “Hymietown.” Rev. Jackson had enjoyed good relations with the Jewish community in Chicago, but the episode caused an uproar, especially among Jewish voters.

Rev. Jackson compounded the controversy by at first denying that he had made the remark and suggesting that he was the victim of a “conspiracy.” He was also slow to disavow the support of Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan, who had a history of making antisemitic remarks.

Rev. Jackson eventually apologized for the “Hymie” remark and intensified efforts to reach out to Jewish voters. But he did not change his views on the Middle East, consistently expressing sympathy for Palestinian rights. Rev. Jackson was the first major candidate for U.S. president to advocate the creation of a Palestinian homeland, a position that became official U.S. policy but was widely considered politically unacceptable at the time.

To the relief of Democratic Party officials, Rev. Jackson, after his improved performance in 1988, did not seek the party’s presidential nomination in 1992. But his civil rights and political activism did not diminish. He traveled incessantly, and regularly pushed himself through 18- and 20-hour workdays.

In 1997, Rev. Jackson’s Rainbow/PUSH Coalition (formed by the merger of Operation PUSH and the National Rainbow Coalition, which he founded in the 1980s) started the Wall Street Project. It was modeled on his earlier efforts to win economic benefits for African Americans and other minorities, and it targeted major corporations whose hiring and other business practices Rev. Jackson described as objectionable.

Financially, it was far more successful than Operation PUSH, reporting millions of dollars in contributions to various Rainbow/PUSH Coalition affiliates and giving Rev. Jackson access to the highest levels of corporate America.

Rev. Jackson also remained an important figure within the Democratic Party. His registration drives added millions of mostly Democratic voters to the rolls. He was a close ally of President Bill Clinton and one of his spiritual counselors during the impeachment process after the Clinton-Monica Lewinsky scandal. Rev. Jackson campaigned hard for Democratic presidential nominees: Vice President Al Gore in 2000, Sen. John F. Kerry in 2004 and Obama in 2008.

“Jesse mobilized a lot of African Americans,” said David Bositis, a former political analyst with the Washington-based Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies and an expert on Black voting. “When the Democrats took back the Senate in 1986, it was a direct function of what Jesse had started in 1984. It was a trend that was already underway, but he greatly accelerated Black participation in the Democratic Party.”

But Rev. Jackson was never without critics among African American leaders. One who emerged relatively late in his life was Al Sharpton, the flamboyant New York preacher and onetime protégé of Rev. Jackson’s who learned the art of attracting and using media attention from his mentor.

Sharpton clearly aspired to replace Rev. Jackson in the hierarchy of Black leaders. As Sharpton was maneuvering, Rev. Jackson endured his most serious personal crisis.

In 2001, the National Enquirer reported that Rev. Jackson had fathered a girl, Ashley, with Karin L. Stanford, a former executive director of a Rainbow/PUSH affiliate in Washington. Rev. Jackson apologized to his family and followers.

“I love this child very much and have assumed responsibility for her emotional and financial support since she was born,” he said in a statement. “I fully accept responsibility and I am truly sorry for my actions.”

Rev. Jackson briefly lowered his public profile but was soon back, leading his various endeavors. And neither Sharpton nor other rivals of the post-King era matched his prominence or influence.

Although immersed in Democratic politics, Rev. Jackson held only one elective office, a ceremonial one. He maintained a home in Washington and in 1990 was elected the District of Columbia’s shadow senator, a position created to lobby Congress for statehood. Rev. Jackson called it a “moral crusade.” He served one term and did not seek reelection in 1996.

In 2000, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, by Clinton, who had appointed him a special envoy to Africa three years earlier. In 2023, he announced he was retiring from the Rainbow PUSH Coalition.

Rev. Jackson and his wife had five children. Complete information on survivors was not immediately available.

His son Jesse Jackson Jr., a Democrat, represented an Illinois district in Congress from 1995 to 2012, and he served two years in prison after pleading guilty in 2013 to spending $750,000 in campaign money on personal items. (“My heart burns,” Rev. Jackson told the AP in 2012. “As I always say to my children, champions have to play with pain. You can’t just walk off the field because you’re hurt.”) He announced in October that he was running for his former congressional seat, launching his campaign on the Rev. Jackson’s 84th birthday.

Another son, Jonathan, has served in Congress since 2023, when he took over the Illinois seat held by 30-year incumbent Bobby L. Rush.

Marshall Frady, a Jackson biographer, observed that from an early age, Rev. Jackson sensed that he had the gifts to overcome the circumstances of his birth and that he set out to use those gifts to make himself “a moral hero” in the wider society from which he was excluded.

“It’s not often one encounters a figure who, from such meager beginnings, has so consciously set about constructing himself to such a grandiose measure — and who, even more rarely, has seemed to hold from the start the actual, natural, imposing stuff for it, however rough and rudimentary,” Frady wrote.

Rev. Jackson was born to an unwed teenage mother in the poorest section of his hometown, in the segregated South. By the time he first ran for president, at 42, he had achieved a level of distinction that eludes most people in public life: He was known simply by his first name. He was Jesse. He was somebody.

Washington Post reporter Edward Walsh died in 2014. Adam Bernstein contributed to this report.

The post Jesse Jackson, a leading African American voice on global stage, dies at 84 appeared first on Washington Post.