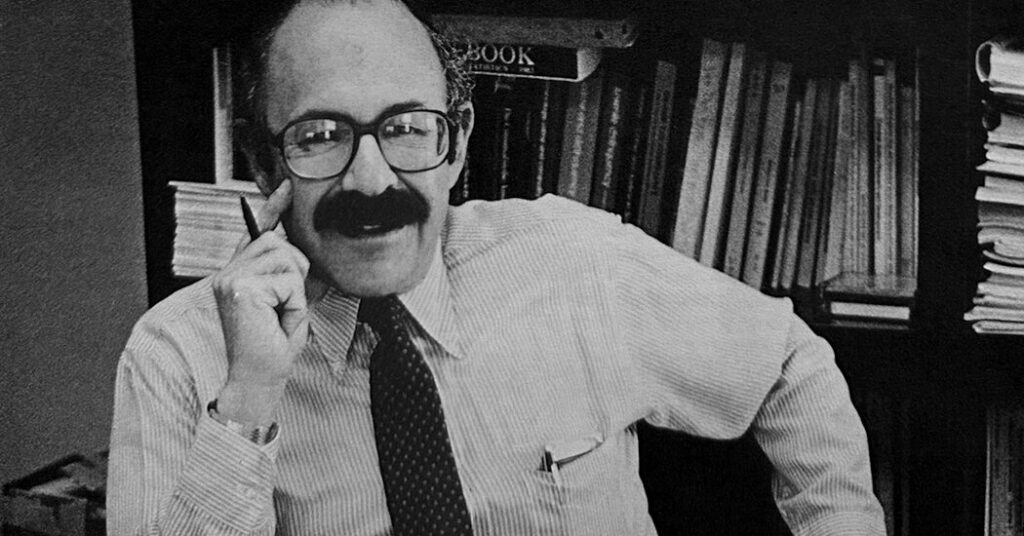

Alfred Blumstein, an intellectual giant in criminology who used mathematical models to reveal the systemic patterns of crime, fundamentally reshaping a field that had long relied on anecdotal evidence and sociological theory, died on Jan. 13 at his home in Canton, Mass., outside Boston. He was 95.

His death was announced by Carnegie Mellon University, where he taught and conducted research from 1969 to 2016.

An engineer and operations research analyst by training, Professor Blumstein used systems theory and quantitative analysis to study criminal behavior much as a logistics planner would analyze the flow of products through a supply chain.

In doing so, he arrived at two singular insights: That criminals have career cycles like those of people in almost any other profession, and that crime rates are shaped by a complex interplay of street violence, the court system and prison sentences.

“Al was the one who really coined what is now the ubiquitous phrase ‘the criminal justice system,’” Daniel Nagin, a criminologist at Carnegie Mellon, said in an interview. “He really identified the connections that people hadn’t thought about before.”

Professor Blumstein, who won the field’s highest honor, the Stockholm Prize in Criminology, in 2007, stumbled into the discipline.

In 1966, he was evaluating counterinsurgency tactics in Vietnam for a Department of Defense think tank when officials from President Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration asked him to lead a task force on science and technology for a landmark crime commission.

“I made it clear that I knew absolutely nothing about crime or criminal justice and thus questioned how I could provide reasonable leadership to such a task force,” he wrote in the Annual Review of Criminology in 2020. “Furthermore, I had no sense of how they found me.”

Still, Professor Blumstein was intrigued by the proposition.

He assembled a team of engineers and analysts who had been trained, as he had, in operations research, a field that emerged during World War II, when scientists began using mathematical modeling to improve military operations.

As the task force began its work, Professor Blumstein quickly realized that criminology was stuck, as he once put it, in the “low-tech, quill-pen era.”

He recalled a sense of disillusionment with “the people who felt they knew what was going on in crime and behavior,” he said in an oral history for the American Society of Criminology. “We came away with a feeling that the state of knowledge was impressively naïve and primitive.”

Professor Blumstein’s task force created a diagram of the various stages of crime and its repercussions — from arrest to prosecution, and from the courts to corrections.

“Operations research is really discovering the physics of the human systems in which we operate every day,” Richard Larson, an operations research professor at M.I.T., said in a tribute to Professor Blumstein. “He says, ‘I’m going to look at this as a system. I’m going to invent the physics of the criminal justice system.’”

After joining Carnegie Mellon several years later, Professor Blumstein created a computer program that simulated the ripple effects shown in the diagram, helping policymakers understand the downstream events at every stage of the system.

For instance, if police substantially increased arrests, court backlogs might follow, putting pressure on prosecutors to offer more plea bargains, which could lead to reduced sentences, prison overcrowding and the early release of dangerous offenders to make room for new prisoners.

“He had this incredibly unique mind that allowed him to see all of these things systemically, as an independent sequence of events,” Robert Sampson, a criminologist at Harvard University, said in an interview. “Then he was able to really dig down into the details.”

One of Professor Blumstein’s signature ideas was that criminals have careers that tend to peter out with age. That framework helped policymakers and prosecutors figure out who should be incarcerated and for how long.

He was especially fascinated by drug dealers, particularly during the crack cocaine epidemic in the 1980s.

Because dealers were typically older teenagers and young adults, imprisoning them didn’t shrink the market; there were plenty of others ready to step in. And their replacements were often younger, and more scared, and thus more likely to carry a gun.

Soon, there were ripple effects.

“Young people are tightly networked, and so their buddies started carrying guns, and their buddies started carrying guns,” Professor Blumstein said in 1999. “And we saw a massive growth in homicides in the ’80s, attributable to young people with guns.”

Alfred Blumstein was born on June 3, 1930, in the Bronx, the only child of Samuel and Shirley (Yellin) Blumstein. His parents divorced when he was 2, and he was raised by his mother, who worked in a bakery.

After graduating from the Bronx High School of Science in 1947, he enrolled at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, where he majored in electrical engineering on the advice of an uncle, who told him that if the Great Depression ever returned, he could always open a radio repair shop.

In 1948, he transferred to Cornell University, where he studied engineering physics. After graduating in 1951, he joined the Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory (now Calspan Corporation) in Buffalo. He simultaneously pursued a master’s degree in statistics at the University of Buffalo, studying with some of the earliest practitioners of operations research.

His first paper, “A Monte Carlo Analysis of the Ground Controlled Approach System,” used mathematical modeling to analyze the reliability of aircraft landing systems in poor weather.

In 1956, he returned to Cornell, where he was among the first graduates of the university’s doctoral program in operations research, in 1960.

Professor Blumstein married Dolores Reguera in 1958. She survives him, along with their children, Lisa Gutwillig and Ellen and Diane Blumstein; and four grandchildren.

Ever the engineer, Professor Blumstein was matter-of-fact in reflecting on his career.

“I feel that I’ve become a leader in the field of criminal analysis and criminal justice, not because I knew anything,” he said in 2018, but simply because he had brought “technical perspectives and analytic skills” to dealing with issues that no one had thought to examine that way.

The post Alfred Blumstein, Who Transformed the Study of Crime, Dies at 95 appeared first on New York Times.