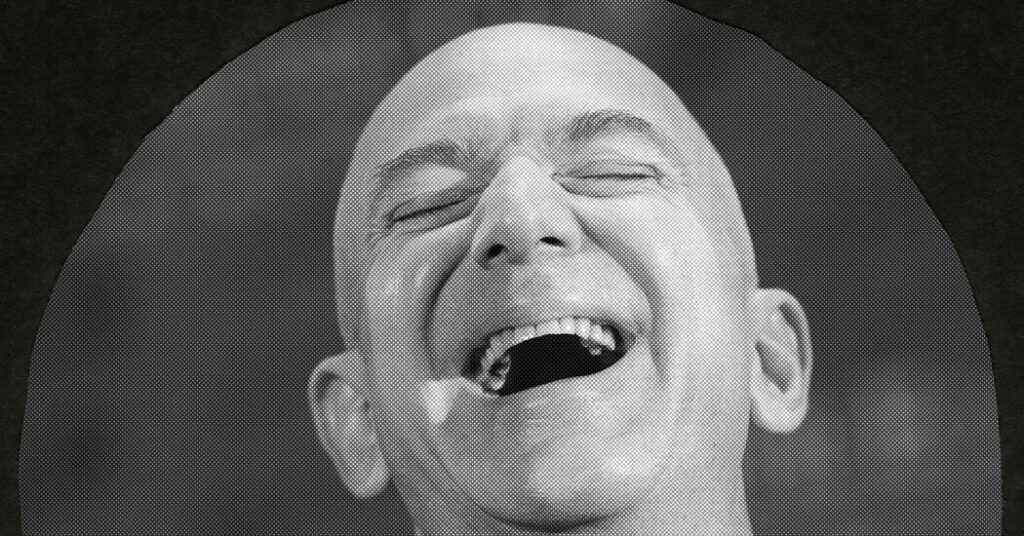

In June 2017, in one of those strange turns of life, I found myself at a dinner in a palazzo in Turin, Italy, sitting next to Jeff Bezos. We had both been invited to speak at a conference convened by an Italian billionaire to discuss the future of newspapers, I as the editor of HuffPost and Bezos as the owner of The Washington Post, which he had bought four years earlier.

I was surprised and, I’ll confess, a little delighted to find myself alongside the man of the hour. Bezos had cut quite a figure at the conference — offering a passionate case for plowing more resources into the heart and soul of the newspaper he pledged to rebuild.

“What they needed was a little bit of runway and the encouragement to experiment, and to stop shrinking,” he said of The Post’s newsroom. “You can’t shrink your way into relevance.” Under his ownership, the paper had added about 140 reporters and rounded the corner to profitability on the back of its journalists’ verve in breaking big stories.

This was music to my ears. It had been an especially bruising month for the industry, and hundreds of journalists had lost their jobs. I had been asked to slash the staff of HuffPost, which I had joined six months earlier, as part of a cost-cutting exercise tied to our parent company’s acquisition of Yahoo. For reasons I could scarcely understand, the deal required laying off 39 journalists, along with more than 2,000 other employees. Yet here was one of the richest and most celebrated business titans in the world urging the opposite course.

As we dug into our sumptuous meal in an ancient hall filled with media grandees, I made a nervous, self-deprecating crack about being a cynical wretch out of place amid the splendor. Bezos quickly corrected me. Great journalists, he said, were not cynical. They were skeptical, as they should be. I offered up a sheepish grin, charmed to hear him echo the credo of my earliest, most grizzled newsroom mentors. Maybe, I thought, this guy was worth trusting.

Turns out the joke was on me, and on journalism. Last week The Washington Post laid off nearly half its staff — according to a recent accounting from the newsroom’s guild — removing brave foreign correspondents, axing its celebrated sports section, gutting its metro reporting staff and more. The cuts, the paper’s leaders said, were aimed at stemming losses and enticing Bezos to keep investing.

The paper was, in other words, attempting to shrink its way into relevance — not with its audience but with its unfathomably wealthy, highly distracted owner, whose fortune has more than doubled in the nine years since I met him. Its newly unemployed journalists, by contrast, face a bleak job market, as their colleagues and friends pass a digital tin cup to raise money to support them.

This wanton destruction took me back to that encounter with Bezos. Why, I wondered, had I trusted him? Trust is an elusive quality nowadays, seemingly vanishing from public life. That disappearance is particularly acute in news media, as new research this week from Pew underscored. An analysis of polling found that 57 percent of Americans “express low confidence in journalists to act in the best interests of the public.”

On its face, this looks like an existential problem for journalism. What good is reporting the news if people don’t trust it? Restoring trust, everyone tends to agree, is a worthy goal. But in an age of digital platforms, algorithmic filtering and declining media literacy, there is no simple recipe for doing so. More fundamentally, the standard explanation for why trust in journalism has plummeted — and so implicitly how one would go about fixing it — is misleading.

The conventional story goes something like this. Once, journalists stuck to the facts and reported the world as it was, hewing to the who-what-where-when, giving each side a chance to present its case and letting readers make up their own minds. Then, amid the great social upheavals of the 1960s and ’70s, journalists became partisans and the news became slanted to represent one side. The problem accelerated with the advent of new venues where journalism appeared: cable news in the 1980s, and most shatteringly, the social media that emerged in the 2000s.

But there’s a problem with this account: It leaves out what journalism actually looked like. The period from the 1970s to the turn of the century, when trust in news organizations fell sharply, was a golden age of news gathering, one in which newspapers had fat profit margins and invested heavily in high-quality journalism. Far from a time of failure, it was a period of astonishing advances in quality and ambition.

The early triumphs of that era — the Pentagon Papers, published by The Times, and The Washington Post’s Watergate investigations — are legendary. Yet more generally the period was marked by a deep cultural shift in journalism, away from rote reporting on the events of the day and toward more aggressive investigations and more analytical writing about an increasingly complex world. The stature of journalists rose: Out went screwball comedies like “His Girl Friday,” and in came serious thrillers like “All the President’s Men.”

At the end of the century, a journalism scholar published a fascinating comparative study of regional newspapers in the early 1960s and the late 1990s. “Papers of the 1960s seem naïvely trusting of government, shamelessly boosterish, unembarrassedly hokey and obliging,” Carl Sessions Stepp, the researcher, wrote. Newspapers of the ’90s were “better written, better looking, better organized, more responsible, less sensational, less sexist and racist and more informative and public-spirited.”

This sounds, you might think, salutary for the health of democracy. But it may have been precisely this move, away from deferential stenography and toward fearless investigation, that led to declining trust in the news media. Aggressive, probing and accountability-oriented journalism held up a mirror to American society — and many Americans didn’t like what they saw.

“As news grew more negative and more critical, people had more reason to find journalism distasteful,” the media scholar Michael Schudson wrote in a provocative essay on the problem of assessing trust in journalism. “What people do not like about the media is its implicit or explicit criticism of their heroes or their home teams.” No one, famously, likes the bearer of bad news.

Thinking back to that dinner with Bezos, I realized that something similar had happened. He flattered my chosen profession, reassuring me that it was not a cynical undertaking but something much more noble. He told me, in short, what I wanted to hear — and won my trust. In the intervening years, Bezos has apparently decided that his flattery is better aimed at a very different audience: Donald Trump.

During the 2024 presidential campaign, Bezos notoriously demanded that The Post spike its planned endorsement of Kamala Harris, at great cost to the paper. After the election, he donated $1 million to Trump’s inaugural committee and joined the row of plutocrats at the inauguration. Amazon paid $40 million for the rights to a documentary about Melania Trump, spent tens of millions more to market the movie and donated to Trump’s absurd White House mega-ballroom project. It’s certainly one way to win trust.

The Post’s loss is others’ gain. Its best-known journalists have streamed out the door, joining thriving news organizations like The Atlantic, The Wall Street Journal and The Times. These companies’ success, built on aggressive and independent reporting, makes me wonder whether the hand-wringing about trust is misplaced. In this new gilded age, maybe we should set aside trust and — as Bezos himself once urged — embrace skepticism.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.

The post I Trusted Jeff Bezos. The Joke’s on Me. appeared first on New York Times.