In August 1964, the Federal Bureau of Investigation found the bodies of three murdered civil rights workers in an earthen dam on a farm outside Philadelphia, Miss., following their disappearance a month and a half before. The slaying of civil rights activists was not unusual in Mississippi. Its white population had lynched more Black people than any other state. Black activists trying to register Black voters were routinely brutalized and killed. Medgar Evers, the NAACP Mississippi field secretary, was assassinated on his front steps the year before, and no one had been brought to justice.

But this was different. One of the slain civil rights activists, James Chaney, was Black. But the other two, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, were white. The national response reflected that. The F.B.I. operated no central office in Mississippi, as it did in many other Southern states, yet more than 150 agents from outside the state swarmed the Delta looking for the missing men. Northern newspapers sent contingents of journalists, and all the major networks covered the story, with Walter Cronkite calling it “the focus of the whole country’s concern.” President Lyndon B. Johnson met with Schwerner’s and Goodman’s parents

The response to the deaths confirmed a cold calculus made by Mississippi’s civil rights strategists when they decided to recruit elite white college students and young professionals to help in the struggle to democratize the state: In America, white lives matter.

But in daring to risk their lives and fight on the side of Black Americans against racial apartheid, Goodman and Schwerner crossed a deadly line. To white supremacists, they were race traitors. And throughout American history, race traitors not only lose the protections of whiteness, but also often become the targets of a particular type of violence, one designed to warn other white people against the costs of fighting — and therefore, delegitimizing — white hegemony.

Last month, Renee Good and Alex Pretti joined this long but seldom spoken-of American tradition when they were killed by federal agents in Minneapolis while standing up for people of color ensnared in the Trump administration’s racialized deportation campaign.

While Trump officials moved to sully their reputations, Nick Fuentes, a white supremacist who in 2022 dined with President Trump at Mar-a-Lago, characterized the pair as betraying their whiteness by standing up for immigrants of color. “We are outnumbered by nonwhites,” he said on his livestreaming show. “And you feel bad about this race traitor? That’s what they are. You feel bad about this lesbian poet and Alex Pretti, the male nurse? You feel sorry for these race traitors that laid down their life in defense of this scheme?”

America’s racial caste system, which places white people on top, has existed since before the country was founded. And yet there have always been white people who have worked against and betrayed notions of racial hierarchy, rejecting the fictions that undergird them and the illegitimate power that racial caste justifies. These people are perhaps the most powerful weapon against these systems.

That’s why, like so many of the archetypal race traitors before them, the willingness of Good and Pretti to put themselves in danger for the cause of racial justice proved an unparalleled galvanizing force, one that simultaneously affirms the best about America, and the worst.

The first person to be executed for treason in the United States was not a spy or someone who sold secrets to a foreign government. It was not a Confederate general who took up arms against his government. It was an abolitionist named John Brown.

A religious man, Brown had long opposed slavery on moral grounds, becoming a conductor on the Underground Railroad and training Black communities in free states how to arm themselves against slave catchers. But as slavery continued to expand across the West and with the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, Brown came to believe that the only way to end slavery was to overthrow it by force.

In October 1859, Brown led a raid on the federal armory at Harpers Ferry in what was then Virginia, intending to arm enslaved people to rise up against their enslavers. Brown’s group killed several people before he was captured and charged with murder and conspiracy to incite the revolt. The Commonwealth of Virginia considered a white man’s taking up arms to liberate Black people an act of treason, punishable by death.

A true believer, Brown understood the costs. “If it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice,” he wrote as he awaited trial, “and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel and unjust enactments, I submit; so let it be done!”

He was convicted by a jury and hanged from the gallows. “To have this white man saying, I will speak truth to power that slavery is fundamentally wrong and it needed to be abolished, and I do not want this racial entitlement because it is based on something as heinous as owning human beings,” says Carol Anderson, a historian in the African American Studies department at Emory University. “Lord have mercy, that is dangerous.”

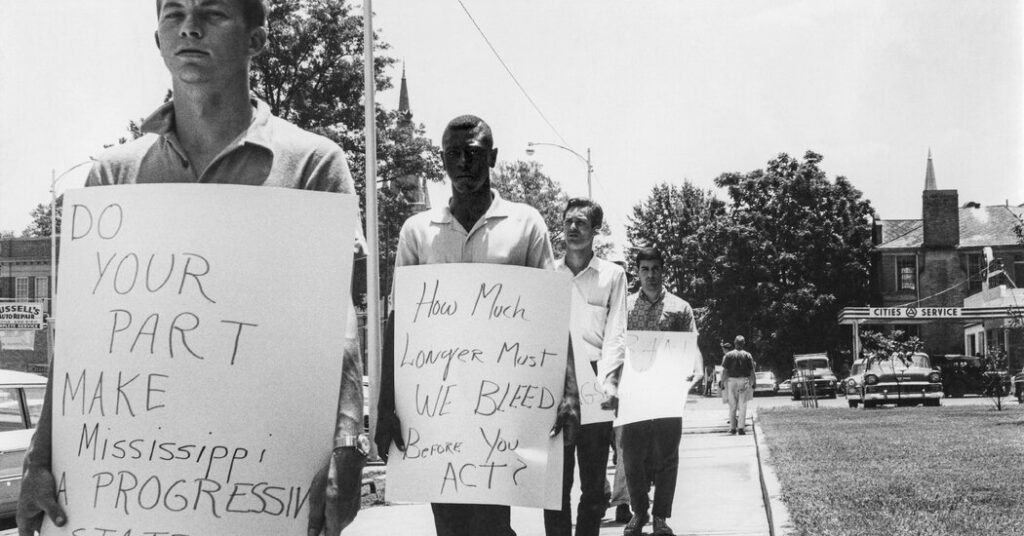

One hundred and five years later, Schwerner and Goodman joined the realm of martyred race traitors working on behalf of the descendants of people who had been enslaved in John Brown’s time. The following year, weeks apart in 1965, James Reeb, a white father of four and Unitarian minister living in Boston, and Viola Liuzzo, a white mother of five from Detroit, were murdered by white supremacists in Selma, Ala. They’d come to support the fight for voting rights after police officers brutally beat Black marchers there in what became known as Bloody Sunday.

As would the deaths of Good and Pretti, the deaths of these white people shocked the conscience of white Americans, drawing national news coverage and widespread condemnation even from many who had been silent. Liuzzo had not been the first mother to die in the civil rights struggle, but after her death, five women’s organizations issued a joint statement saying that Liuzzo’s murder as she sought to help “make the promises of democracy a reality for citizens of all races, was cruel beyond relief.” They urged their members to get involved and assure Liuzzo’s family that “the sacrifice of this mother was not in vain.” A Michigan reverend expressed hope that after her death, more white people would be compelled to act, saying, “Today America hurts.”

Vice President Hubert Humphrey went to pay his respects to Liuzzo’s family, telling them that President Johnson had declared that the “whole country” grieved with them. In a news conference later that day, Humphrey said that a “turning point had been reached in the civil rights struggle” and that voting rights legislation, which countless Black Americans had lost their lives trying to achieve, would most likely pass by May.

The white Southern power structure understood something that research has since supported: Small numbers of mobilized people — perhaps as little as 3.5 percent of the population — can force transformative structural change.

So white Southern officials tried to overcome the spectacle and power of white death by calling the disappearance of Goodman and Schwerner a hoax. After the killings of Liuzzo and Reeb, white officials moved to smear them, claiming they were communists and accusing Liuzzo of being a drug user and sexually promiscuous.

After the killings in Minneapolis, administration officials followed a similar playbook, claiming — without evidence — that Good and Pretti were far-left domestic terrorists whose deaths were justified because they had intentions of harming immigration officials. Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem accused Pretti, who had a legal gun on his body but was holding just a cellphone when tackled and shot multiple times, of wanting to “massacre” agents. Stephen Miller, the White House deputy chief of staff, called Pretti a “would-be assassin.” Neither has offered proof of these claims.

Good and Pretti were not the first people to be killed by federal immigration agents since Trump began his deportation dragnet and their shootings were not the first to be caught on camera. According to the Marshall Project, federal officers have shot and killed at least three other people in recent months. The Times found that since September, ICE agents opened fire on at least nine people, killing a Mexican immigrant whose shooting was also caught on video that challenged the official government narrative justifying the agents’ actions. But Pretti and Good were gunned down on crowded streets as fellow protesters were filming. The shocking circumstances of their deaths made them impossible to ignore. As did their whiteness.

And like the slain white activists before them, their deaths provoked a response that other deaths had not. Mass protests swept the nation. Democrats threatened to impeach Noem. The right-wing podcaster Joe Rogan called ICE “the Gestapo.” And the conservative columnist Bill Kristol posted two words that would have been unthinkable, even for many Democrats, just a few weeks before: Abolish ICE.

While white nationalists like Fuentes see race traitors as threats to their agendas, others see them as assets. Noel Ignatiev, a whiteness scholar who studied the way racial identity was constructed to create a hierarchy that privileged white people in our political, social and economic order. He also founded the journal Race Traitor, believing the term was aspirational for white Americans like himself. He encouraged white people to reject power structures that used racial oppression to erode democracy and divide working-class people from one another in ways that hurt not just Black and other racial minorities, but white people themselves.

For activists and organizers and everyday people struggling against this administration’s policies, the race traitor label evokes an inspiring and hopeful lineage: white people who are willing to give up the protection whiteness offers to stand for justice with those who are fewer in number and have far less power.

After the election of 2024, many Black Americans and members of other marginalized groups felt deeply betrayed by a white majority (and a near Latino majority) that sent Trump back to the White House. As Trump has done what they had warned he would do — eviscerate civil rights protections, target L.G.B.T.Q. Americans, round up immigrants, erode democratic institutions — Black activists have largely moved their organizing underground, leaving it to white people to get in the streets this time.

One of those activists is Alicia Garza, who co-founded the Black Lives Matter Global Network in 2013 following the acquittal of the man who killed 17-year-old Trayvon Martin. After the murder of George Floyd in 2020, she watched the movement ascend when for the first time a majority of white Americans supported it. Since then she has seen solidarity and racial justice efforts crushed by the “anti-woke” frenzy that has swept the nation and helped usher in the second Trump administration.

But the response in Minneapolis seems to have shifted something, inciting masses of people to action around the country. After months of silence and capitulation across industries and institutions, Garza said, many white Americans are determining that for all the backlash against diversity efforts and civil rights, they don’t like that their neighbors are being targeted simply for how they look, that they are rejecting the unchecked power they are witnessing even if it is supposed to be to their benefit. They are, she said, realizing that their safety and liberation is tied to the safety and liberation of society’s most marginalized.

Of course, Garza is struck by what it took to push many to decide they must fight back. “I get why people might be mad that it took white people being executed for folks to turn up, I get that, I really do,” Garza told me. “We don’t make the rules of racism, OK? So as long as this country is organized in this way, then there has to be a clear strategy around how to interrupt it, and part of that strategy has to be white people defecting.”

The post The Transformative Power of the White ‘Race Traitor’ appeared first on New York Times.